Prior to beginning an exercise program with a client, fitness professionals must conduct a variety of intake assessments to check for risk factors and get a baseline for future progress tracking.

Fitness professionals must be familiar with acquiring health history forms, taking anthropometric measurements, and conducting resting assessments.

Introduction to Comprehensive Client Assessments

Comprehensive client assessments encompass a variety of subjective and objective assessments used to determine a client’s risk factors, goals, and current physiological measurements to establish a baseline.

The overall resting assessment sequence is as follows:

- Medical history form including lifestyle questionnaire and PAR-Q

- Resting heart rate

- Resting blood pressure

- Bodyweight

- Height

- Circumference measurements

- Skinfold measurements

While all clients must fill out the medical history and related forms prior to engaging in physical activity under the trainer’s supervision, the specific additional assessments will vary depending on client goals and health history, comfort with the assessments, and the availability of equipment.

A comprehensive fitness assessment provides subjective and objective information including any risk factors relevant to training, resting physiologic measurements, and anthropometric measurements such as height, weight, and skinfold measurements that allow for objective progress tracking.1, 2

As a general rule for safety, coaches must advocate that their client see their primary physician prior to beginning or increasing the intensity of an existing exercise program if needed. However, clients who select “yes” to any of the questions on the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) must obtain medical clearance prior to the trainer beginning an exercise program.1, 2

Medical History Questionnaire

A preparticipation health screening includes a medical history, lifestyle questionnaire, and Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q). Often, these forms are combined into a single intake form, but they can be separate as well.

Medical history forms should gather the following information:

- Current medications, especially for metabolic conditions

- Injury history

- Cardiovascular risk assessment via the PAR-Q

The main pre-existing screen is offered by the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) and includes some variation of the following questions:

- Has your doctor ever said that you have a heart condition or high blood pressure?

- Do you feel pain in your chest at rest or when performing physical activity?

- Do you lose your balance because of dizziness or do you ever lose consciousness?

- Have you ever been diagnosed with another chronic medical condition (other than heart disease or high blood pressure)?

- Are you currently taking prescribed medications for a chronic medical condition?

- Do you have a bone, joint, or soft tissue problem that could be made worse by a change in your physical activity?

- Has a doctor ever said that you should only do medically supervised physical activity?

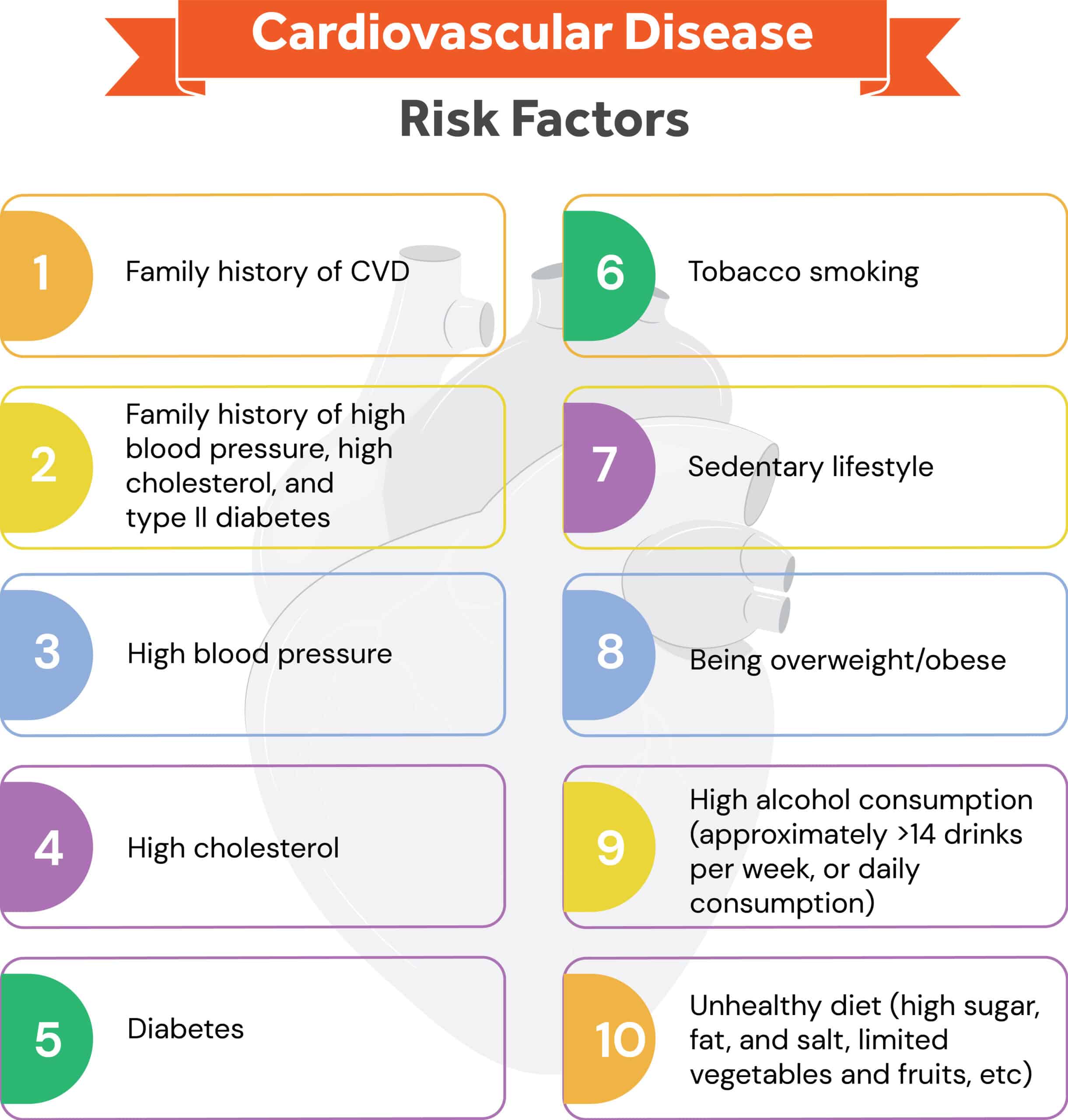

Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors

In addition to the PAR-Q form, intake forms should also assess cardiovascular risk factors. Based on the number of risk factors, fitness professionals can make generalized decisions about safe, optimal programming. Additionally, a client with multiple risk factors should also get medical clearance from a qualified healthcare professional prior to beginning any exercise program.

The following are the risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) to consider on top on the PAR-Q questionnaire responses:

Risk Factor Assessment:

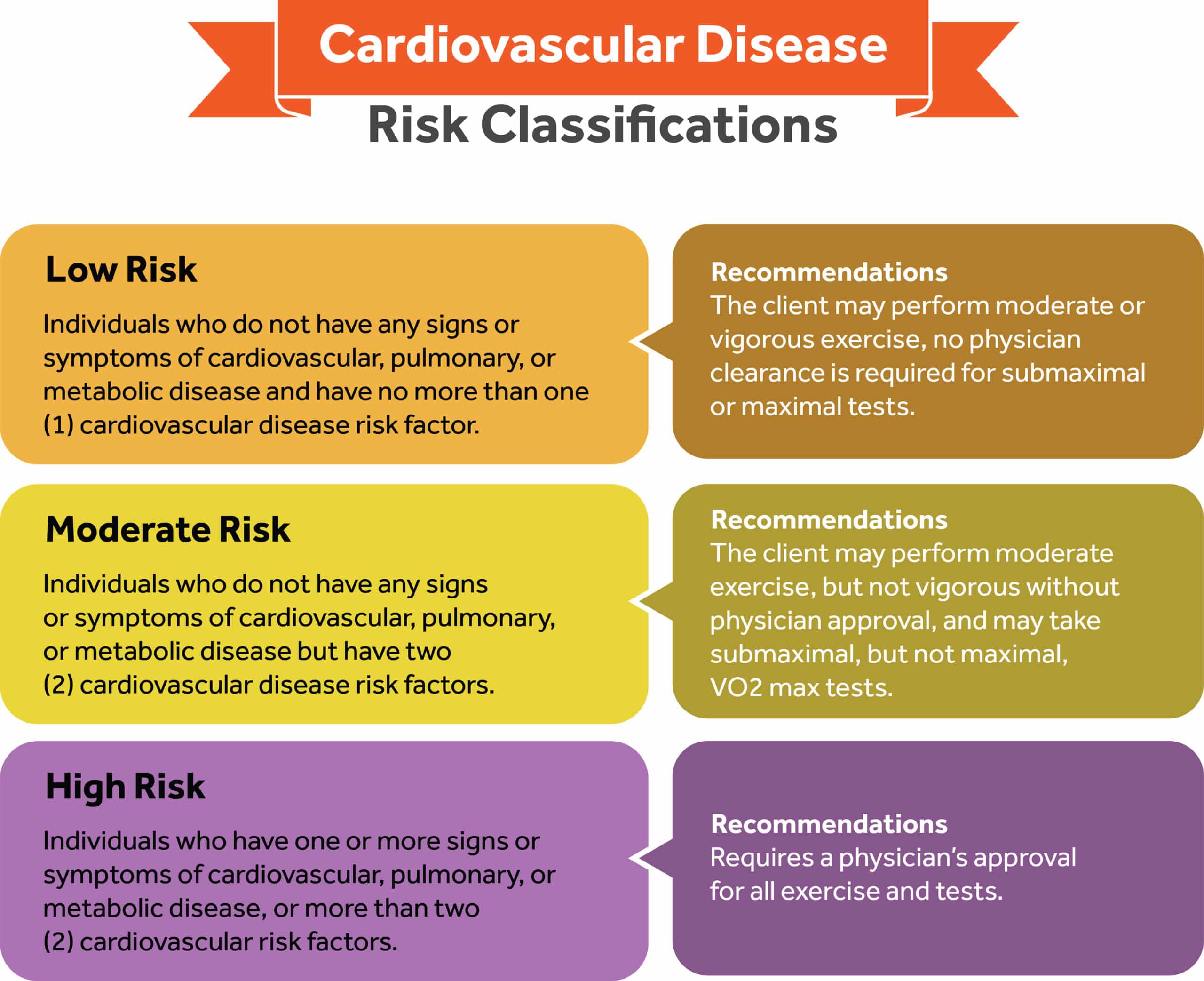

The following stratification can be used to generalize about risk factors and make appropriate recommendations:

- Low Risk: individuals who do not have any signs or symptoms of cardiovascular, pulmonary, or metabolic disease and have no more than 1 cardiovascular disease risk factor.

- Moderate Risk: individuals who do not have any signs or symptoms of cardiovascular, pulmonary, or metabolic disease but have 2 cardiovascular disease risk factors.

- High Risk: individuals who have one or more signs or symptoms of cardiovascular, pulmonary, or metabolic disease, or more than 2 cardiovascular risk factors

Recommendations Based on Risk Levels:

- Low Risk: client may perform moderate or vigorous exercise and no physician is needed for submaximal or maximal tests

- Moderate Risk: client may perform moderate exercise but not vigorous without physician approval, and may take a submaximal, but not maximal, VO2 test

- High Risk: requires a physician’s approval for all exercise and tests

Lifestyle Factors for Injury Risks

Collecting information about a client’s profession and recreational activities helps personal trainers determine common movement patterns, as well as typical energy expenditure levels during the course of an average day.

This kind of information helps personal trainers begin to recognize imperative signs about the client’s musculoskeletal structure and function, potential health and physical limitations, and boundaries that could affect the safety and value of an exercise program. For example:

- Extended periods of sitting could contribute to muscular imbalances, prolonged periods of low energy expenditure throughout the day, and potentially poor cardiorespiratory conditioning.

- Repetitive movements can cause musculoskeletal injury and dysfunction. Also, these can create pattern overload in muscles and joints, which may lead to tissue trauma and eventually kinetic chain dysfunction, especially in jobs that require a lot of overhead work or awkward positions such as construction or painting.4, 16

Physiological Assessments

Resting Heart Rate (RHR)

RHR is influenced by factors such as fitness status, fatigue, body composition, drugs/medication, alcohol, caffeine, and stress.1, 7, 10

The assessment of RHR is an indicator of a client’s overall cardiorespiratory health as well as fitness status. RHR is a good indication of overall cardiorespiratory fitness, whereas exercise HR is a strong gauge of how a client’s cardiorespiratory system responds and adapts to exercise.

Resting Rate Classifications:

- Sinus bradycardia: slow HR, anything less than 60 beats per minute.

- Normal sinus rhythm: 60-100bpm.

- Sinus tachycardia: fast heart rate, which is greater than 100bpm.

Heart rate is either easily recorded at either the base of the wrist (radial), or against the side of the trachea (carotid). To gather an accurate recording it is best to teach clients how to record their resting HR on rising in the morning. Clients can test their RHR three mornings in a row and average the three readings

Resting Heart Rate Procedure:

- Locate anatomic site

- Gently press down with two fingers over palpation site

- Count the number of pulsations for a specific time period (6, 10, 30 or 60 sec)

- Begin counting the first pulsation as 0 when the timing is initiated simultaneously or, if a lag time occurs after the start time, begin with the number 1

- Calculate beats per minute via multiplication based on the time interval

- 6 second count – multiply by 10

- 10 second count – multiply by 6

- 30 second count – multiply by 2

Blood Pressure (BP)

Blood pressure is defined as the outward force exerted by the blood on the vessel walls.

It is measured using an aneroid sphygmomanometer, which consists of an inflatable cuff, a pressure dial, a bulb with a valve, and a stethoscope. When assessing BP, it is imperative to use calibrated equipment that meets certification standards and to follow standardized protocol.

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) is the pressure created by the heart as it pumps blood into circulation via ventricular contraction. Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) represents the pressure that is exerted on the artery walls as blood remains in the arteries during the filling phase of the cardiac cycle, or between beats when the heart relaxes.6, 18

To determine systolic pressure, listen for the first observation of the pulse. Diastolic pressure is determined when the pulse fades away.

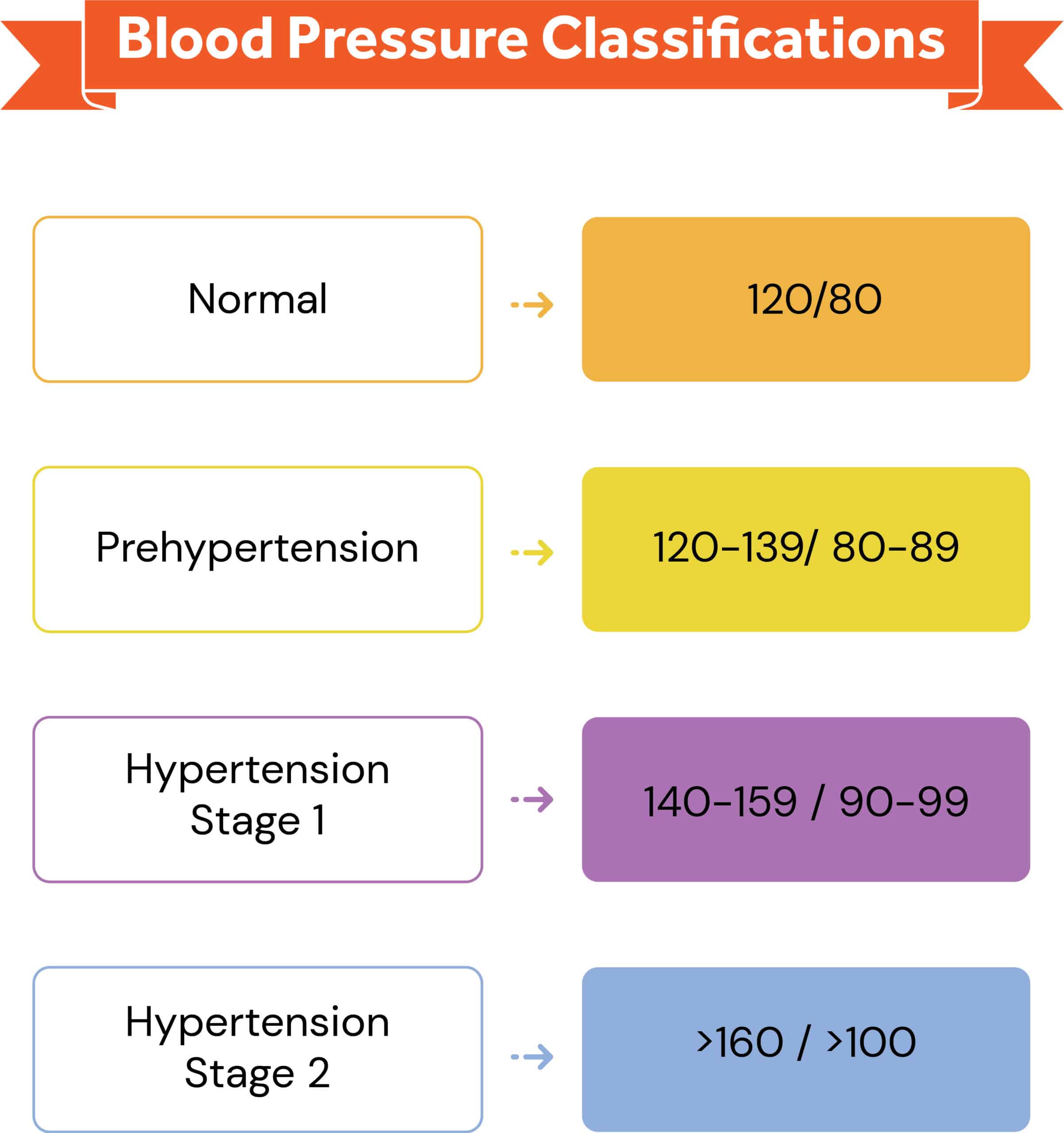

Blood Pressure Classifications:

- Normal: 120/80 mmHg

- Prehypertension 120-139/ 80-89

- Hypertension Stage 1: 140-159 / 90-99

- Hypertension Stage 2: above 160 / above 100

Resting Blood Pressure Measurement Procedure:

- Position yourself to hear the BP and see the manometer scale.

- Make sure the stethoscope is flat and placed completely over the client’s brachial artery.

- Client should be seated, with feet flat, legs uncrossed, and the arm free of any clothing and relaxed. The arm and back should be well supported by furniture.

- Center the bladder of the BP cuff over the client’s brachial artery.

- Position the client’s arm so it is slightly flexed at the elbow.

- Firmly place the bell of the stethoscope over the artery located in the antecubital fossa.

- Inflate the cuff to approximately 20 mm Hg above the SBP, if known.

- Up to 140-180 mm Hg for a resting BP

- Up to 30 mm Hg above disappearance of the radial pulse

- Deflate the cuff slowly 2 -3 mm Hg per heartbeat by opening the air exhaust valve on the hand bulb.

- Record measures of SBP and DBP in even numbers rounding up.

- Rapidly deflate the cuff to zero after the DBP is obtained.

- Wait for 1 full minute before repeating the BP measurement.

Body Composition Testing

There are many methods to assess body composition. Each of these methods gives the trainer insight in determining the best course of action for a fitness program.

Body composition refers to the relative percentage of body weight that is fat versus fat-free tissue, more commonly reported as “body fat percentage.”

Fat-free mass can be defined as total body weight excluding stored fat, including muscle, bones, water, connective and organ tissues, and teeth, whereas fat mass includes essential fat (vital for normal body functions such as neural pathways and hormones) and nonessential fat (storage fat or adipose tissue).13, 16

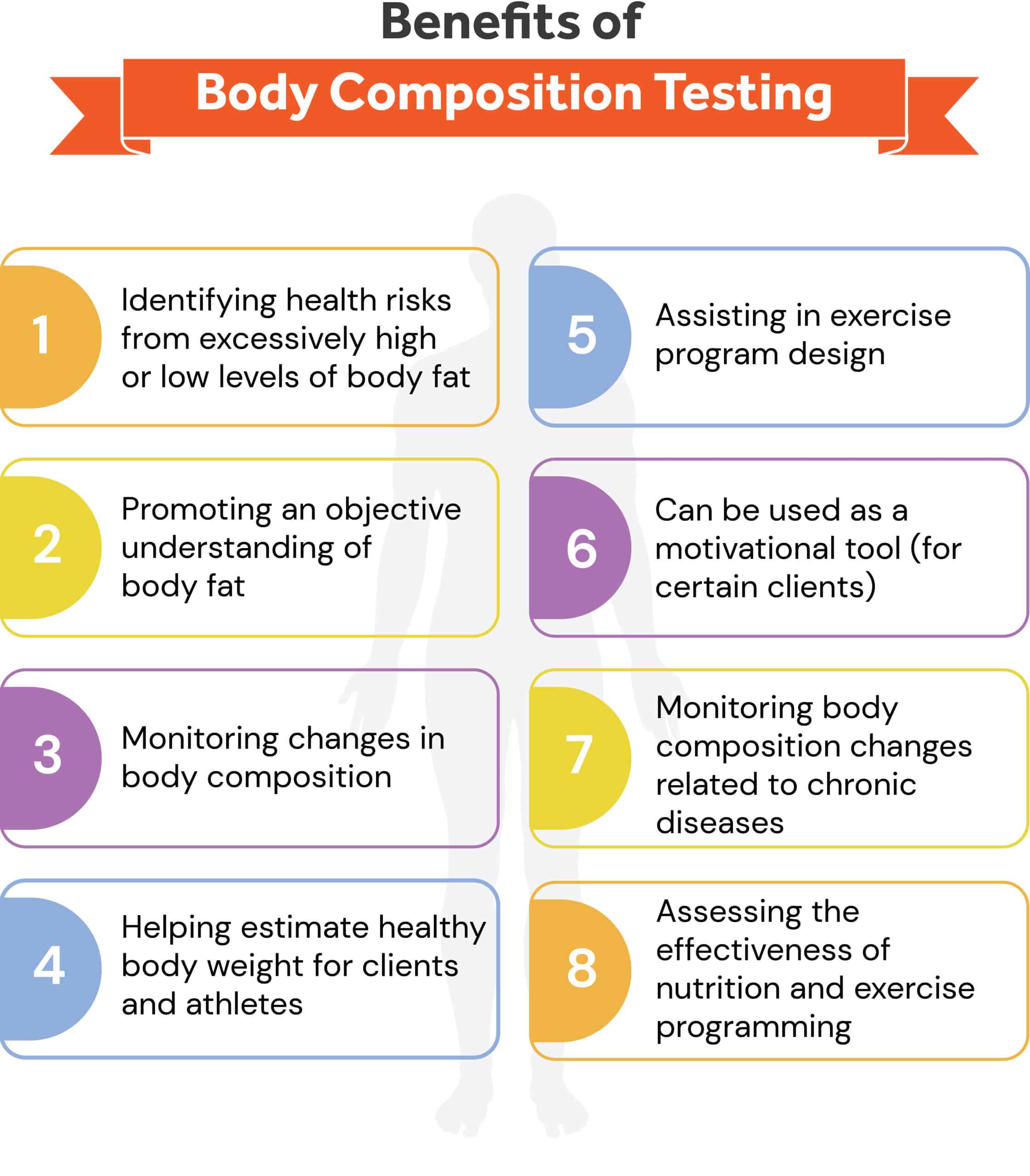

Body composition testing can:

- Identify client’s health risk for excessively high or low levels of body fat

- Promote client’s understanding of body fat

- Monitor changes in body composition

- Help estimate healthy body weight for clients and athletes

- Assist in exercise program design

- Be used as a motivational tool (for certain clients)

- Monitor changes in the body composition that are associated with chronic diseases

- Assess the effectiveness of nutrition and exercise programming

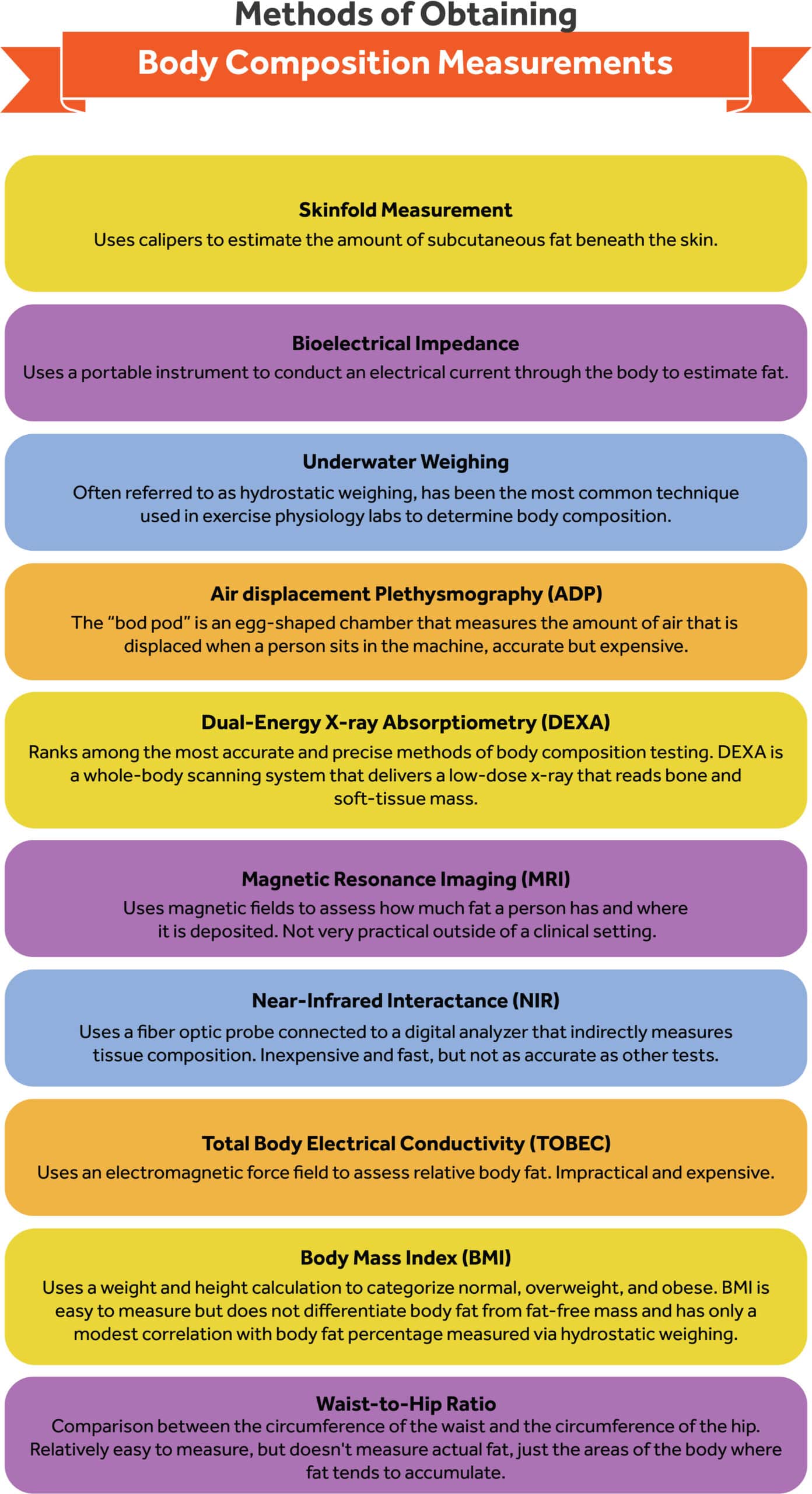

In order to obtain correct calculations, technology has provided many different brands of equipment with different procedures, calculations, and modes of use. The various modes of obtaining results of body composition include:1, 2, 14

- Skinfold measurement: uses a caliper to estimate the amount of subcutaneous fat beneath the skin.

- Bioelectrical Impedance: uses a portable instrument to conduct an electrical current through the body to estimate fat. This is based on the hypothesis that tissues that are high in water content conduct electrical currents with less resistance than those with little water (such as adipose tissue)

- Underwater weighing: often referred to as hydrostatic weighing, has been the most common technique used in exercise physiology labs to determine body composition.

- Air displacement Plethysmography (ADP): the “bod pod” is an egg-shaped chamber that measures the amount of air that is displaced when a person sits in the machine. Two valves are needed to determine body fat: air displacement and body weight. ADP has a high accuracy rate but the equipment is expensive.

- Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA): Ranks among the most accurate and precise methods. DEXA is a whole-body scanning system that delivers a low-dose x-ray that reads bone and soft-tissue mass. DEXA has the ability to identify regional body-fat distribution.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): uses magnetic fields to assess how much fat a person has and where it is deposited. Since MRIs are located in clinical settings, using an MRI solely for calculation of body fat is not practical.

- Near-infrared interactance (NIR): uses a fiber optic probe connected to a digital analyzer that indirectly measures tissues composition (fat and water). Typically, the biceps are the assessment site. Calculations are then plugged into an equation that includes height, weight, frame size, and level of activity. This method is relatively inexpensive and fast, but generally not as accurate as other techniques.

- Total body electrical conductivity (TOBEC): uses an electromagnetic force field to assess relative body fat. Much like the MRI, it is impractical and too expensive for the fitness setting.

In order to begin body composition testing and related calculations, the following information is needed: height, weight, and circumferences of selected areas.

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Body Mass Index (BMI) is one of the commonly used calculations that delineates weight categories based on

BMI = body mass (kg) divided by the height squared (m2) = (kg / m2).

The major shortcoming of BMI is that it does not differentiate body fat from fat-free weight and has only a modest correlation with body fat percentage measured via hydrostatic weighing.

Waist-to-Hip Ratio

Waist-to-hip ratio is a comparison between the circumference of the waist and the circumference of the hip. This ratio reflects the relative distribution of body fat, which correlates to multiple metabolic risk factors.

Individuals with more weight or circumference on the waist are at higher risk of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease than individuals who are of equal weight but have more of their weight distributed on the extremities.1, 2, 4

With the help of formulas and calculations, the Skinfold test with the use of calipers is still used on individuals who are under 30% body fat and under the care of an experienced personal trainer.

Skinfold Measurements

Skinfold measurements are a more precise way to estimate body fat percentages without expensive equipment. Skinfold measurements are most reliable on individuals who are under 30 percent body fat.

Skinfold measurements are taken via handheld calipers and then entered into one of several formulas depending on which measurements are taken.

While skinfold measurements can be fairly reliable, it takes substantial practice under qualified supervision to consistently take accurate, reliable measurements.

Skinfold Measurement Sites

- Abdominal: vertical fold; 2 cm to the right side of the umbilicus

- Triceps: vertical fold; on the posterior midline of the upper arm, halfway between the acromion and olecranon processes, with the arm held freely to the side of the body

- Biceps: vertical fold; on the anterior aspect of the arm over the belly of the biceps muscle, 1 cm above the level used to mark the triceps site

- Chest/Pectoral: diagonal fold; one-half the distance between the anterior axillary line and the nipple (men), or one-third of the distance between the anterior axillary line and the nipple (women)

- Medial calf: vertical fold; at the maximum circumference of the calf on the midline on the midline of its medial border

- Midaxillary: vertical fold; on the midaxillary line at the level of the xiphoid process of the sternum. An alternate method is a horizontal fold taken at the level of the xiphoid/sternal border on the midaxillary line

- Scapular: diagonal fold (45-degree angle); 1-2 cm below the inferior angle of the scapula

- Suprailiac: diagonal fold; in line with the natural angle of the iliac crest taken in the anterior axillary line immediately superior to the iliac crest

- Thigh: vertical fold; on the anterior midline of the thigh, midway between the proximal border of the patella and the inguinal crease (hip)14

Procedures:

- All measurements should be made on the right side of the body with the subject standing upright.

- Caliper should be placed directly on the skin surface, 1 cm away from the thumb and finger, perpendicular to the skinfold, and halfway between the crest and the base of the fold.

- Pinch should be maintained while reading the caliper.

- Wait 1-2 sec before reading caliper.

- Take duplicate measures at each site and retest if duplicate measurements are not within 1-2mm.

- Rotate through measurement sites or allow time for skin to regain normal texture and thickness.14

Summary

Health history, resting, and anthropometric assessments for all new clients are important for multiple reasons. Health history and PAR-Q is vital to obtain to ensure the client is physically capable of safely participating in exercise.

Resting assessments further flag risk factors and give a baseline for cardiorespiratory fitness prior to any performance testing.

Finally, anthropometric assessments give quantitative data about the client’s body composition, which further assists in designing optimal exercise programs and also allows objective measurement of progress.

While the specific assessments will vary depending on the individual client and training environment, all clients must complete the health history and PAR-Q before beginning any exercise under trainer supervision.

References

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

- Hargens T, Edwards ES, Musto AA, Piercy K. ACSM’s Resources for the Personal Trainer. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2022.

- Thomas S, Reading J, Shephard RJ. Revision of the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q). Can J Sports Sci.1992;17:338-345.

- Pate R, Pratt M, Blair S, et al. Physical activity and public health:a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine.JAMA. 1995;273:402-407.

- Going S, Davis R. Body composition. In Roitman JL (Ed.): ACSM’s Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:396.

- Chobanian, A.V. et al. (2003). JNC 7 Express: The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressu-re. NIH Publication No. 03-5233. Washington, D.C.: National Institutes of Health & National Heart, Lung, and Blood lnstitute

- Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007 ;1 1 6 (9): 1 08 1 -9 3

- Kaminslry LA, editor. ACSM\ Health-Related Physical Fitness Assessment Manual.4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2073.192 p.

- Riebe D, Franklin BA, Thompson PD, et al. Updating ACSM’s recommendations for exercise preparticipation health screening. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2075;47 (ll):247 3-79.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for coronary heart disease: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(7):569-72.

- Baumgartner, T.A., A.S. Jackson, M.T. Mahar, and D.A. Rowe. 2007. Measurement for Evaluation in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 8th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Beam, W., and G. Adams. 2011. Exercise Physiology Laboratory Manual, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Eckerson, J.M., J.R. Stout, T.K. Evetovich, T.J. Housh, G.O. Johnson, and N. Worrell. 1998. Validity of self-assessment techniques for estimating percent fat in men and women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 12: 243-247.

- Golding, L.A. 2000. YMCA Fitness Testing and Assessment Manual, 4th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Harrison, G.G., E.R. Buskirk, J.E. Carter Lindsay, F.E. Johnston, T.G. Lohman, M.L. Pollock, A.F. Roche, and J.H. Wilmore. 1988. Skinfold thicknesses and measurement technique. In: Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual, T.G. Lohman, A.F. Roche, and R. Martorell, eds. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. pp. 55-70.

- Heyward, V.H. 2010. Advanced Fitness Assessment and Exercise Prescription, 6th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Morrow, J., A. Jackson, J. Disch, and D. Mood. 2011. Measurement and Evaluation in Human Performance, 4th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Pickering, T.G., Hall, J.E., Appel, L.J., Falkner, B.E., Graves, J., Hill, M.N., Jones, D.W., Kurtz, T., Sheps, S.G., and E.J. Roccella. 2005. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals. Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in humans. A statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension 45: 142-161.

- Prisant, L.M., B.S. Alpert, C.B. Robbins, A.S. Berson, M. Hayes, M.L. Cohen, and S.G. Sheps. 1995. American National Standard for nonautomated sphygmomanometers. Summary report. American Journal of Hypertension 8: 210-213.