Behavioral coaching is a key skill for fitness professionals. While most trainers can dveloper a training program and demonstrate exercise techniques, transforming sedentary individuals from not exercising to engaging in a regular, periodized exercise program is the true crux of being an effective personal trainer. This is particularly true for those who work with weight loss clients who are otherwise sedentary, and other client types who may be resistant to exercise participation.

This chapter discusses the key skills trainers can employ to help move clients from being inactive to participating in regular exercise over long periods of time, and ideally, for the rest of their lives.

Introduction to Behavioral Coaching

It is no surprise that most Americans today do not exercise as recommended. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, only 23.2% of Americans actually meet the recommended amount of aerobic and muscle-strengthening activity.1 This is despite the fact that exercise has been proven to enhance sleep, increase energy, boost strength, manage weight, reduce stress and anxiety, and improve mood.2

Furthermore, having a regular exercise routine can help to manage and prevent diseases such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, osteoporosis, arthritis, heart disease, and stroke.2 While many folks would like to be active, it is often the habit formation and change in routine that can make it challenging to get started and stick with an exercise routine.

This is where knowledge around behavior change and habit formation can serve as a catalyst for exercise professionals to better support their clients. This chapter is specifically intended to explore how fitness professionals can work with their clients to understand where they are, and how they can work toward reaching their goals.

Some of the concepts and ideas that will be discussed include the transtheoretical model for stages of change, motivational interviewing, working through barriers, strategies to improve exercise adherence, social influences on exercise, and psychological benefits.

Stages of Change Model

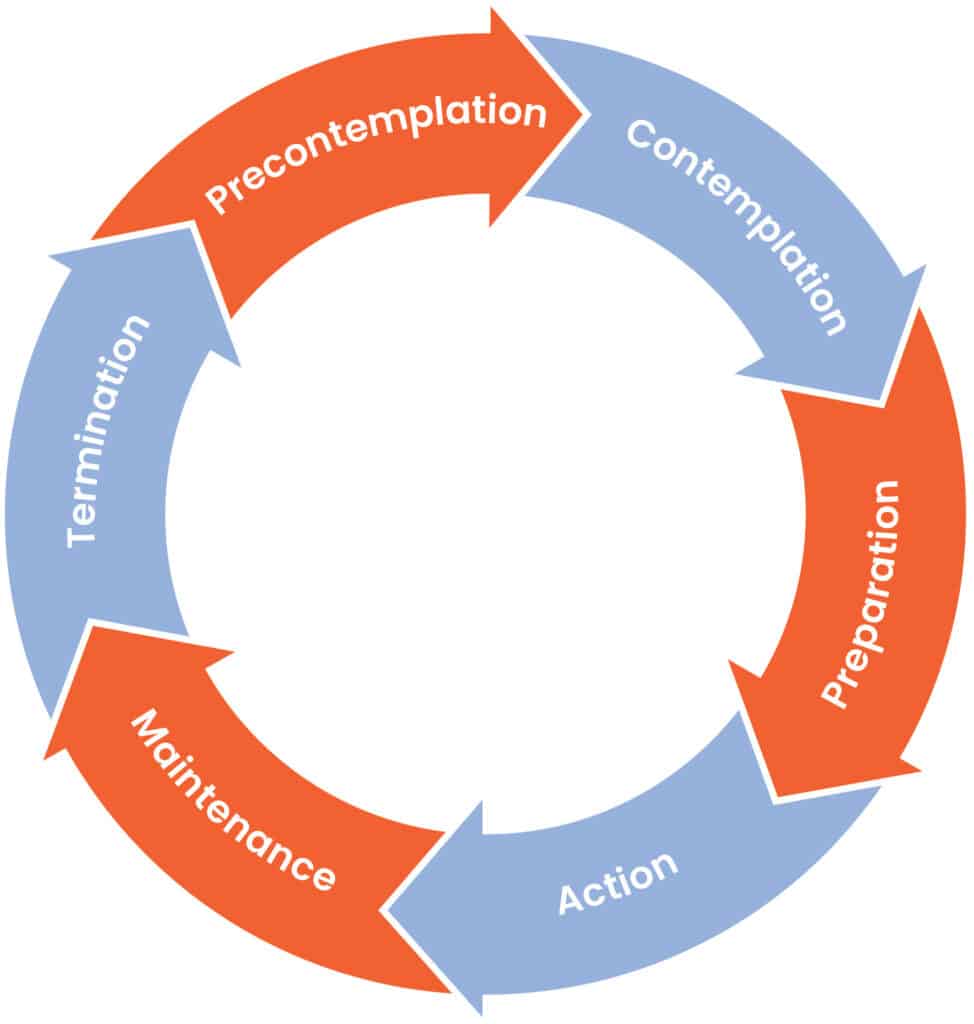

There are five stages of change when looking at behavioral modification: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Relapse is also something to consider when thinking about the stages of behavior change and will be addressed in this chapter as well.

For the most effective behavioral change coaching, exercise professionals must meet clients where they are in their current stage and help them process through it as opposed to trying to force change. Ultimately, the client must feel empowered to pursue and maintain their fitness goals, and thoughtful behavioral coaching is one of the more reliable methods to achieve this state.

Precontemplation

People who are in this stage of change are not yet ready and have no desire to make a change. It is likely that they do not already have any exercise routine, and do not have intentions or thoughts around starting one within the next six months.

Individuals in this stage are unlikely to meet with a personal trainer. However, if someone in the precontemplation stage does happen to meet with an exercise professional, the best way to help them is to gently educate them around the benefits of exercise and steer them toward self-awareness.

Basic, easy-to-follow resources are the best type of educational material for clients in the precontemplation stage.

In addition to educating clients, fitness professionals should inquire further with the client regarding their feelings about exercise. This type of conversation is also a good time to debunk any myths the client may have about exercise.

The following are a few questions that may be helpful to ask individuals in this stage:

- What comes up for you when you think about exercise?

- Are you open to talking about some of the benefits of exercise?

- What have you heard about exercise that stands out to you?

The fitness professional should never attempt to force the client to become interested or ready to begin exercising. The coach’s primary roles during this stage of change are providing education through credible resources and fostering self-awareness.

Contemplation

Individuals in the contemplation stage are not exercising yet, but they are interested in getting started within the next six months. This stage gives fitness professionals a great opportunity to have a meaningful impact on the client’s decision to move forward with their exercise routine. At this stage, the fitness professional must ask questions to get closer to understanding where the client’s remaining ambivalence lies.

At the contemplation stage, the client typically has some level of motivation to exercise and likely understands the benefits of exercise to a certain extent. However, they still have some misunderstandings about what it means to be active or a continuing belief in one or more myths about exercise.

To best support people in the contemplation stage of change, the fitness professional must continue providing education. In this stage, individuals benefit from information and resources that support the positive thoughts they have around exercise and a gentle education that helps to redefine any misconceptions they may have.

The following are a few questions that may work well for clients in the contemplation stage of change:

- What do you see being a positive result of exercise?

- What seems to be a negative result of exercise?

- What do you already know about exercise?

Understanding where the client’s ambivalence lies will inform the exercise professional’s next steps. At that point, the exercise professional can provide education and credible resources, along with a positive attitude and motivating presence that keeps the client wanting to come back. Gaining this understanding will help the exercise professional to work with the client from the contemplation stage and into the preparation stages.

Preparation

People in the preparation stage of change are exercising but may not have a strong habit or plan established. At this point, they know the benefits of exercise and are motivated to work towards their fitness goals. People in this stage likely need some support in managing expectations and determining realistic goals.

The best way to support people in this stage varies based on the client’s activity, however all support from the exercise professional should focus on the positive outcomes of exercising and help them to build self-efficacy within their exercise plan.

Strategies that are most helpful for people in the preparation stage include the following:

- Goal setting

- Affirming positive behaviors and thoughts about exercise

- Normalizing differences across exercise plans for individuals

- Tapping into previous positive experiences with establishing habits

- Discussing social support

- Generating awareness around potential barriers

- Encouraging a balance of exercise that supports the client’s current capabilities

Action

People in the action stage are active and may have been active for a few weeks or months. They are engaging in a regular, healthy exercise habit, but have not yet reached the 6 month mark. It is important for the exercise professional to help clients in this stage to continue building on what is going well and recognize where there may be barriers or challenges.

The exercise professional can continue to educate clients about the benefits of exercise and build on what they already know and believe. Emphasizing the client’s strengths to further grow that self-efficacy will keep clients feeling motivated and positive about their efforts.

Exercise professionals must learn to adjust the exercise program as needed during the action stage based on the client’s barriers to exercise, as well as to ensure appropriate workout intensity. This requires an understanding of the client current’s challenges on the part of the exercise professional.

Maintenance

At the maintenance stage, clients have been able to maintain their exercise habit for six months or more. They have likely figured out what works well most of the time, but still may slip into previous sedentary habits. Fitness professionals should continue to affirm the clients in this stage, give them regular kudos, and check in on their plans for the future.

Goals can be set to last a bit longer than in previous stages, and should be specific to what the client is experiencing at the present time, and what they expect down the line. The exercise professional can work on keeping the exercise programming in line with the clients changing goals and plans, and should take progression into account.

A trainer can help set two types of goals, outcome and process goals. Process goals are goals that are made to help people reach a more specific goal and will include tracking the progress and a plan of action. Outcome goals are used for assessing whether or not a goal has been achieved and if there should be further action required to meet the goal.

How to Assess Stage of Change

Assessing a client’s stage of change can be done through asking questions that will help to inform what and how much thought the client has or has not already put into their activity goals.

Below are some examples:

- How do you feel about exercise?

- What success have you had with reaching your activity goals?

- What has gotten in the way of exercise in the past? In the last 6 months?

- What has helped you to stick with activity goals so far in your experience?

- What have your best exercise routines looked like?

By learning more about what the client is doing currently, or what they have done in the past, the exercise professional can think through which stage of change they are in currently.

- Is the client lacking interest in starting activity at all? They may be in the precontemplation stage.

- Is the client thinking about starting an exercise plan in the next several months? They may be in the contemplative stage.

- Is the client getting started and experimenting with exercise occasionally? They may be preparing to dive into their goals.

- Is the client already exercising regularly and working through challenges as they come up? This would be a client in the action stage.

- Has the client already been exercising for 6 months or more? This would be a client in the maintenance stage.

Motivational Interviewing

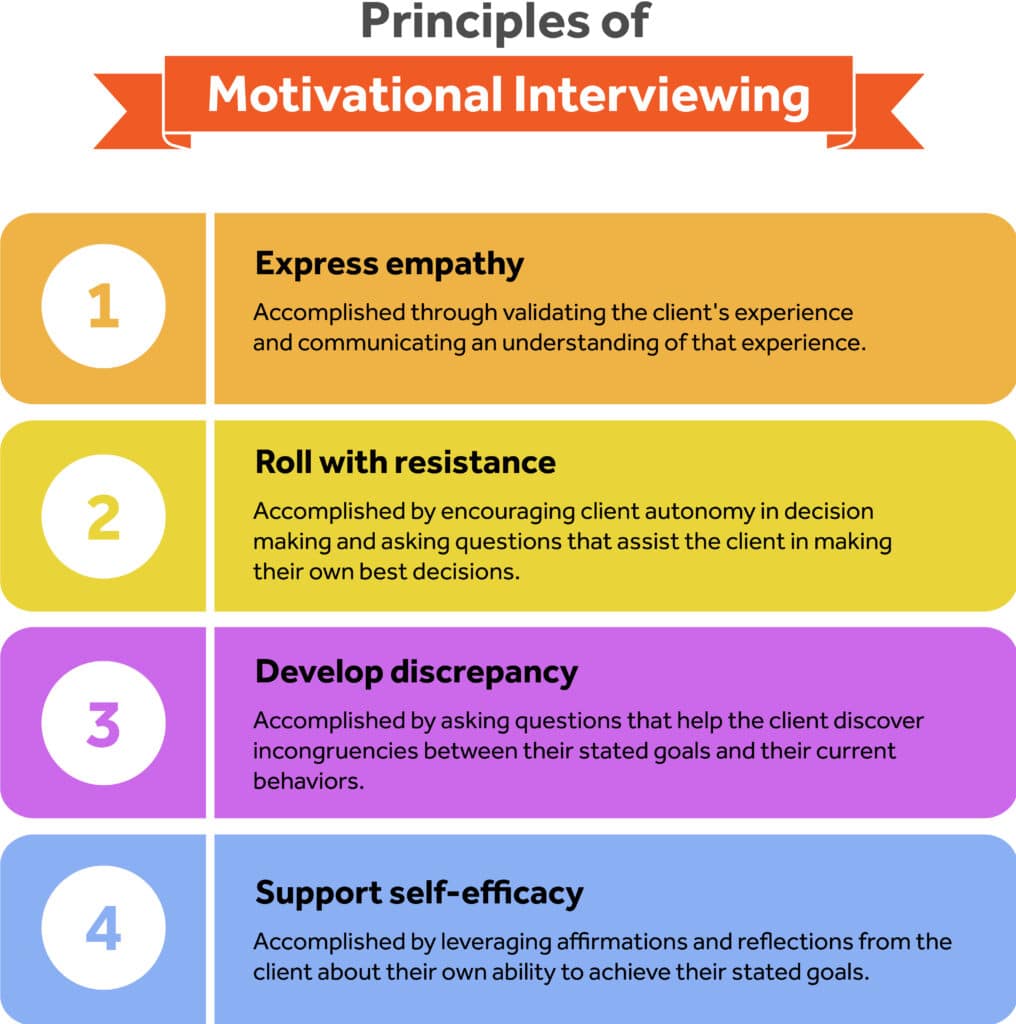

Motivational interviewing is a directive, client-centered counseling style for eliciting behavior change by helping clients to explore and resolve ambivalence.3 With an understanding of the stages of change, motivational interviewing is the next key skill that coaches can use to elicit positive behavior change.

The following are the four main principles of motivational interviewing:

- Express Empathy

- Roll with Resistance

- Develop Discrepancy

- Supporting Self-Efficacy4

Expressing Empathy

Expressing empathy means relating to a client’s experience wholly. This is done by validating their experience, and clearly communicating an understanding of that experience. This is an important skill to leverage when working with individuals who are feeling challenged.

For example, the client can benefit substantially when their coach helps them understand their experience is normal and help them stay positive and feel free from judgment.

Rolling with resistance is about avoiding direct head-on arguments and demonstrating to an individual that they have been heard. At this point, the exercise professional can promote the client’s autonomy to make decisions about their goals versus what the exercise professional thinks is best.

The exercise professional should refrain from the ‘righting reflex.’ This is where the professional in a working relationship jumps in to offer a solution, advice, or suggestion to the client. While often made with good intentions, this advice or suggestion that is contrary to what the clients feels is best for them can create resistance against that advice or suggestion. This is natural human behavior. In this case, it would be more helpful to ask questions that allow the client to develop discrepancy.

Developing discrepancy is where the professional in the working relationship asks questions that allow the client to see how what they are saying or planning on does not necessarily align with their goals or values.

An example where this may come up would be a client sharing that they are motivated to continue with their exercise programming to achieve improved aerobic capability, but then they avoid incorporating aerobic activity in their exercise program. Developing discrepancy here would help the client see how they may be getting in their own way of reaching their goals.

Lastly, building on self-efficacy is where the professional supports the client in not only following through on their goals but also recognizing their own strengths and behaviors that allow them to do so. This can be done by leveraging affirmations and asking clients to reflect on what strengths they used to achieve their goals.

Active Listening

This is at the heart of motivational interviewing. Active listening lets the client know that their trainer or coach stays with them, tracking in the conversation, and curious to learn more. Using verbal cues such as “Hmm”, “Yes”, “Uh-huh” and “Ah” can be one way for a professional to show clients that they follow what the client shares, but to go beyond surface level will also include body language and building on the conversation. Body language should mirror the client and maintain a welcoming presence. Some of the basics on body language would include not crossing arms or legs, maintaining appropriate eye contact, and head nodding. Next, is the exploration of building on the conversation by examining a few other key techniques.

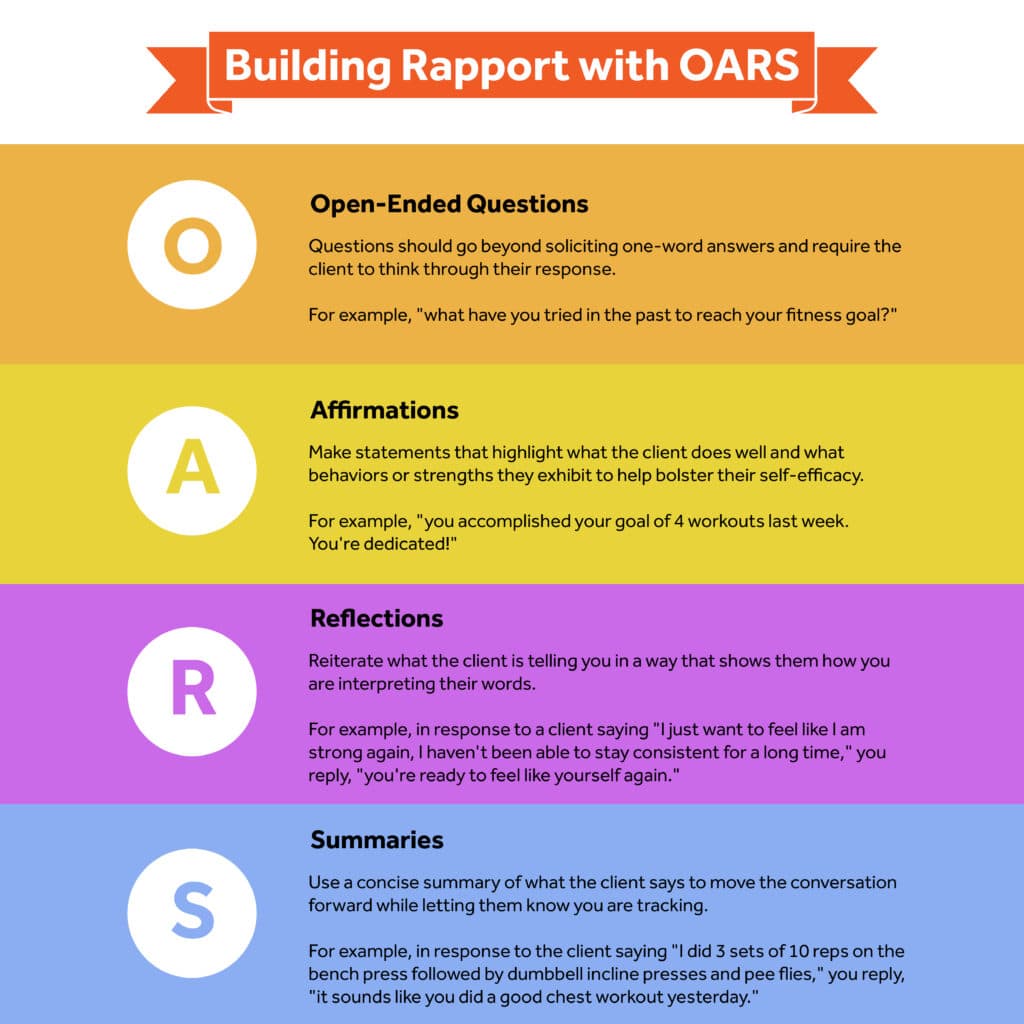

Building Rapport with OARS

This is an acronym for Open Ended Questions, Affirmations, Reflections, and Summaries. Using these four techniques reassures the client that their trainer is fully present.

Open Ended Questions

Open ended questions are inquiries that go beyond ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers. These questions should require the client to think through their responses. Generally, open ended questions begin with ‘what’, ‘where’, and ‘how.’ Take note that questions beginning with ‘why’ are not included here.

Questions that begin with ‘why’ can make the recipient of the question feel as though they are being judged, so are very important to avoid in a trainer-client relationship. The open ended questions used in conversations with clients should build off of what the client has already been sharing.

Affirmations

Statements of what the client is doing well and what behaviors or strengths they are exhibiting will help to bolster their self-efficacy. These statements should go beyond a simple ‘Good job’ and should really encompass specific language about what the client did. For example, “You accomplished your goal of 4 workouts last week! You’re dedicated.”

Reflections

Reflections are statements reiterating what the client is telling the exercise professional in a way that shows the client their trainer interprets their words. Reflections help the client see that their coach actively listens to them and comprehends what they are saying. This goes beyond regurgitating the client’s words.

For example, in response to their client saying “I just want to feel like I am strong again. I haven’t been able to stay consistent for a long time,” their coach might respond with, “you’re ready to feel like yourself again.”

Summaries

This technique can be used to move the conversation forward while letting the client know that their exercise professional tracks what the client is saying. Summaries differ from reflections in that they simply summarize what the client tells the trainer. This is in contrast to a reflection, where the trainer shares their interpretation of what the client is saying.

Summaries help clients to feel heard and are an important step to keep conversations moving forward while demonstrating active listening.

Overcoming Common Barriers to Exercise

At some point during a client’s time adhering to their exercise program, they are going to run into barriers or other challenges that make it difficult to move forward. Overcoming these obstacles will be much easier if the trainer and client address some of the common barriers to starting and adhering to exercise plans.

Time

Lack of time is the most common barrier to participating in exercise.5 As the exercise professional, it can be meaningful to support the client in discovering some awareness around this perceived barrier to achieving goals. Inquiring around the client’s schedule and self-reflection tend to lack the level of detail needed for gaining this type of self-awareness.

People often are not unaware of how much time is spent on social media, browsing the web, or even watching TV. To help clients to gain a higher level of awareness around where their time is being spent, the exercise professional may have them do a ‘time audit.’

This would request that the client takes note of how they are spending their time for a designated period, such as a week. Doing this is meant to help the client to have a clear picture of how they are currently spending their time and may help them to see where they have room to add in a new routine.

Unrealistic Expectations or Goals

Many clients starting out with a new trainer do not have recent experience with an exercise routine. With the best of intentions and eagerness to grow, they may tend to set goals for themselves that are not quite realistic, helpful, or even safe. When set appropriately, goals should help clients to build confidence, self-efficacy, and motivation.

Goals should be challenging enough to keep clients interested and inspired, but realistic enough that they are attainable. It is key for the exercise professional to work with clients to understand why this is important, and how to apply the concept.

Lack of Confidence

For those who are just getting started with exercise, or who have not engaged in an exercise routine in a gym setting, it is common to lack confidence around getting active, and the ability to get active.6

For clients who are lacking confidence, the exercise professional may work with these clients to start with exercise routines that are within their comfort zone to start, such as a walking program. Once the client starts reaching their ‘starter goals’, they will start to gain confidence and feel more comfortable moving forward. This can take some time, and the exercise professional can support the process by continuing to affirm the client’s strengths and behaviors.

Strategies to Improve Exercise Adherence

Once clients get started with their goals, it will become about working with them to adhere to the exercise programming. In addition to having discussions about their barriers, the exercise professional can be proactive about bolstering adherence.

SMART Goal Setting

Working with clients to establish their goals comes up time and time again. At this point, it’s best to discuss how to start the conversation and what tenets are needed for a meaningful goal.

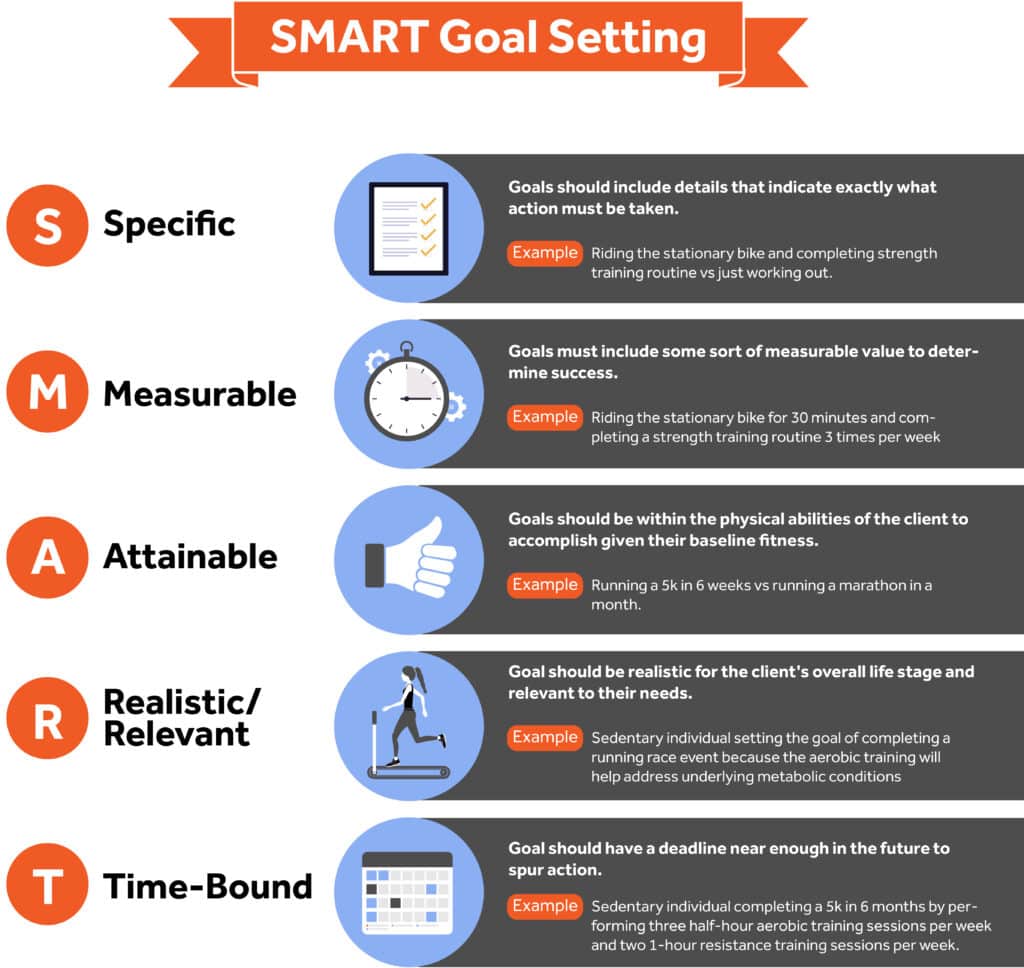

There is a handy acronym that is used in the behavior change world that makes it easy to remember the 5 components of a meaningful goal: SMART. These goals should be Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time Based.

Kicking off the goal setting conversation will start off with the big picture, and then will move to a more granular and specific plan. To start things off and to really understand what is motivating the client to start an exercise program, the following questions can guide the client to think through what their outcome goals are:

- What would success look like 6 months from now?

- What would you like to have achieved one year from now?

- What is your ultimate goal for your exercise program?

- What would you like to be different as a result of your exercise program?

- Once the client has shared more about the direction they’d like to go, and what is important for their success with an exercise program, it will be time to get more specific and determine action steps.

Specific

Goals should include details that indicate exactly what the action is going to be. This means the client should be given the opportunity to think through what exactly it is they are looking to achieve or do via the goal that is being set.

For example, “Going to the gym” is not very specific for an exercise goal, unless the goal is simply to get to the gym. To make this more specific, it may look like this: “Riding the stationary bike and completing a strength training routine.”

Measurable

This component should make it easy to know whether the goal has been achieved or not. There should be some sort of measurable value indicated within the goal, i.e. how many times per week, an increasing cadence, or a certain amount of time.

To build on the goal that was stated above, this may look like: “Riding the stationary bike for 30 minutes and completing strength training routine 3 times per week.”

Attainable

As mentioned previously, goals should always be attainable for the client. This means the goal should take into consideration where the client is at currently, and what is achievable for them to continue to grow. For example, it would not be realistic for someone who hasn’t been running to set a goal to run a marathon in a month. What may be realistic in this example would be a 5k in 4-6 weeks.

Relevant

Goals should always be co-created between the client and exercise professional, with the client’s outcome goals in mind. The SMART goal should be related and relevant to what the client is looking to achieve. For example, if a client is looking to run a marathon, their SMART goal should be centered around running, with cross training that supports the sport.

Time-Based

To ensure the client’s tasks are being prioritized and they are maintaining motivation, it is important to put a realistic, yet ambitious end date for the goal. For example, to build on the marathon goal, if a client wants to run a marathon next year, they may set a goal for the present time that has them reaching a 10 mile run within 4 months.

Setting goals that are as close to SMART as possible will help clients to really think through what it will look like for them to follow through on their goals. This will lead to improved adherence.

Self-Monitoring and Tracking

Self-monitoring or tracking are strategies that can help clients to not only see their progress over time but can also add a layer of self-accountability to their routine. Once a client starts writing down or tracking what they are doing for exercise, they will start to build more self-efficacy. This creates a record of the success that they are seeing so far. There are several different ways a client may track: websites, apps, journals, etc.

Manage Expectations

Clients may come to the exercise professional with visions of how they will go from being inactive to fully integrating exercise into their everyday life. It is important to work toward managing appropriate expectations for the process of establishing an exercise habit.

Discuss with them the length of time it will take to start seeing progress, normalize barriers and roadblocks, bring awareness to the importance of consistency, and connect the dots between where the client is currently and where they’d like to be.

Support

Having the support of an exercise professional, friends, families, or colleagues can be really meaningful to clients. They may look to an individual ‘gym buddy,’ or a family member who keeps them accountable to their goals.

Whatever the support looks like, it will likely come into play time and time again throughout the client’s journey.

A social network can have a profound influence on a client’s physical activity behaviors.7 There are a number of different types of support systems that can help a client’s success with their exercise programming.

Having a positive presence and influence in their corner will add to their feelings of belonging within the exercise community, provide a level of accountability, and help to build motivation. Let’s review the different support mechanisms first:

Instrumental

This is the service-like or required type of support that makes a client’s success possible. An example of this type of support would be a client’s spouse watching the kids twice per week so the client can attend an aerobics class.

Emotional

This support provides a sense of love or care for the client. It is likely to be coming from close friends or family who may lend an ear, provide validation, and encourage.

Informational

This support mechanism involves when the client looks for information, advice, and facts. It is likely that the exercise professional is providing this type of support to clients.

Companionship

This type of support brings a sense of community or belonging. Clients may have a friend that they attend an exercise class with, or who they meet at the gym for workouts regularly.

Some of the social support systems that are common in the exercise world include family or friends, exercise leaders, and exercise groups. Family or friends can offer up emotional or instrumental support where they help the client to feel a sense of hope or inspiration to continue going.

Friends or family may also be instrumental supporters in that they are the ones who make it possible for the client to move forward with their goals: taking responsibility off the client’s plate, financial support to join a gym or class, or driving the client to or from their workouts.

Exercise leaders would be social connections that have a high level of exercise experience, knowledge, or engagement. This may be someone that the client knows already, or it could be the exercise professional working with them to come up with an exercise program.

Finally, exercise groups can be really impactful in creating community and companionship for clients. This may be through an exercise class, a meet-up group, or some other type of exercise community that bolsters support in a group setting.

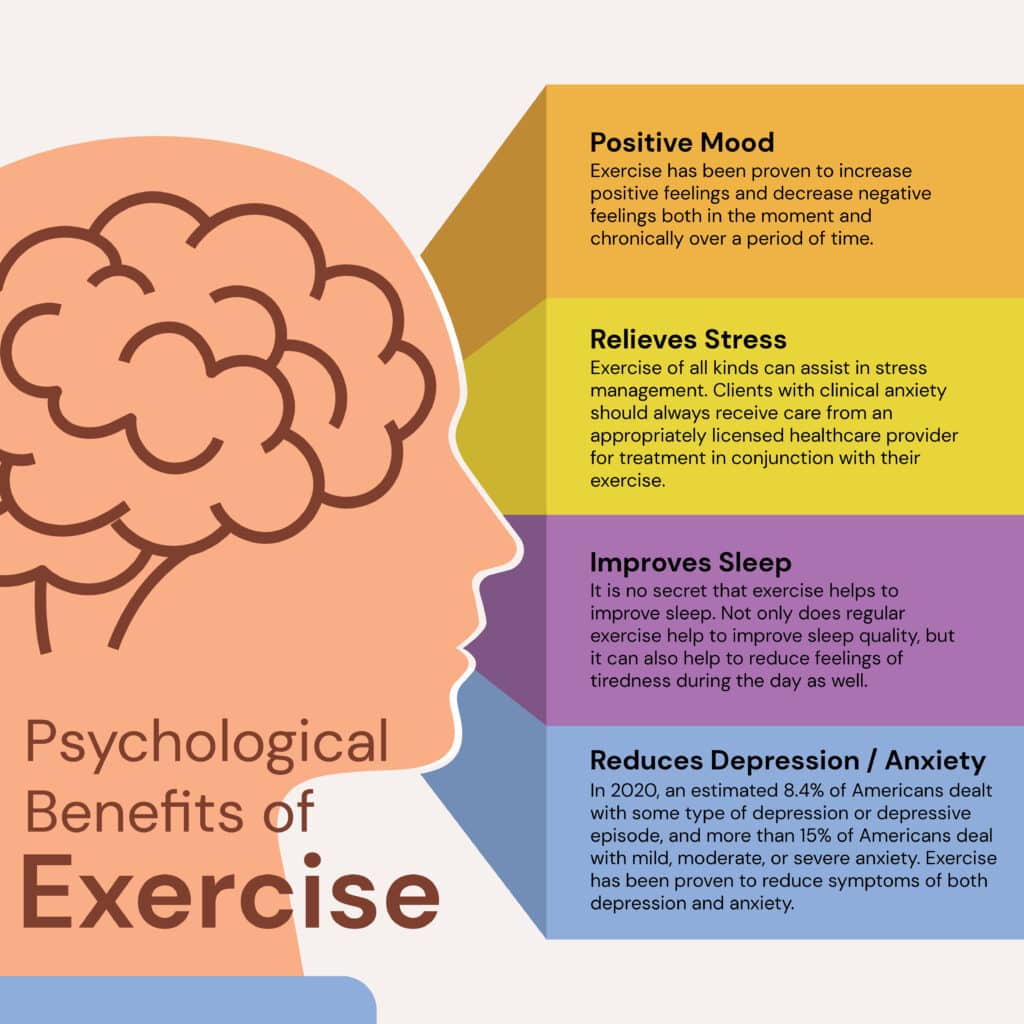

Psychological Benefits of Exercise

Exercise provides psychological benefits through a variety of biological mechanisms. The following are some of the top examples of well-researched benefits of exercise when it comes to mental health and psychology.

Positive Mood

Exercise has been proven to increase positive feelings or mood and decrease negative feelings.8 This occurs both in the moment and holds up over a period of time.

Relieves Stress

Exercise of all kinds can be a catalyst for stress management.9 Whether a positive or negative stressor, finding ways that work well for each individual to manage stress is an important skill. While exercise can be a component of a stress management plan, if there is a clinical issue related to a client’s stress, they should be referred to an appropriate clinician.

Improves Sleep

It is no secret that exercise helps to improve sleep. Not only does regular exercise help to improve sleep quality, but it can also help to reduce feelings of tiredness during the day as well.2

Reduces Depression / Anxiety

In 2020, an estimated 8.4% of Americans dealt with some type of depression or depressive episode, and more than 15% of Americans deal with mild, moderate, or severe anxiety.11, 12 Exercise has been proven to reduce symptoms in both depression and anxiety.13

Summary

Despite the many benefits of exercise, many individuals do not reach the minimum recommended requirements for weekly activity, so it may be up to the fitness professional to determine where in the state of change model their clients are and how to move them along it.

They can first build rapport with the client using OARS, deal with overcoming barriers to exercise, and set SMART goals which help organize expectations into measurable outcomes. All these steps act as psychological tools that can be useful in moving sedentary clients towards an active lifestyle, or they can even help clients who do not currently feel motivated in their fitness pursuits.

References

- “FASTSTATS – Exercise or Physical Activity.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/exercise.htm.

- “Real-Life Benefits of Exercise and Physical Activity.” National Institute on Aging. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/real-life-benefits-exercise-and-physical-activity.

- Rollnick, Stephen, and William R. Miller. “What Is Motivational Interviewing?” Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 23, no. 4 (1995): 325–34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135246580001643X.

- Schultz, Joshua. “Motivational Interviewing Principles: 4 Steps Explained.” PositivePsychology.com, July 11, 2022. https://positivepsychology.com/motivational-interviewing-principles/.

- Lyndall Strazdins, Dorothy H. Broom, Cathy Banwell, Tessa McDonald, Helen Skeat, Time limits? Reflecting and responding to time barriers for healthy, active living in Australia, Health Promotion International, Volume 26, Issue 1, March 2011, Pages 46–54, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daq060

- Hoare, Erin, Bill Stavreski, Garry L Jennings, and Bronwyn A Kingwell. “Exploring Motivation and Barriers to Physical Activity among Active and Inactive Australian Adults.” Sports (Basel, Switzerland). MDPI, June 28, 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5968958/.

- Dollman, James. “Social and Environmental Influences on Physical Activity Behaviours.” MDPI. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, January 22, 2018. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/15/1/169/htm.

- Steinberg, Hannah, Briony R. Nicholls, Elizabeth A. Sykes, N. LeBoutillier, Nerina Ramlakhan, T.P. Moss, and Alison Dewey. “Weekly Exercise Consistently Reinstates Positive Mood.” European Psychologist 3, no. 4 (1998): 271–80. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.3.4.271.

- Jackson, Erica M. “Stress Relief.” ACSM’S Health & Fitness Journal 17, no. 3 (2013): 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1249/fit.0b013e31828cb1c9.

- Connor, Patrick J., and Shawn D. Youngstedt. “Influence of Exercise on Human Sleep.” Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews 23 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1249/00003677-199500230-00006.

- “Major Depression.” National Institute of Mental Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed September 1, 2022. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression#part_2562.

- Terlizzi, M.P.H, Emily P., and Maria A. Villarroel, Ph.D. “Symptoms of Generalized Anxiety Disorder among Adults: United States, 2019.” NCHS data brief. U.S. National Library of Medicine, September 2020. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33054928/.

- Carek, Peter J., Sarah E. Laibstain, and Stephen M. Carek. “Exercise for the Treatment of Depression and Anxiety.” The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 41, no. 1 (2011): 15–28. https://doi.org/10.2190/pm.41.1.c.