Dietary supplements are widely used by athletes and fitness enthusiasts alike.

The Trainer Academy Scope of Practice prohibits recommending specific dietary supplements. However, fitness professionals should have basic knowledge of the widely used supplements and performance-enhancing drugs since many clients take one or more of these substances.

Furthermore, knowledge of the general purpose and proven efficacy of popular supplements, as well as understanding the regulations in the supplement industry is key for discussing safety and rationale for supplements when clients inquire.

Introduction to Supplementation

Dietary Supplementation

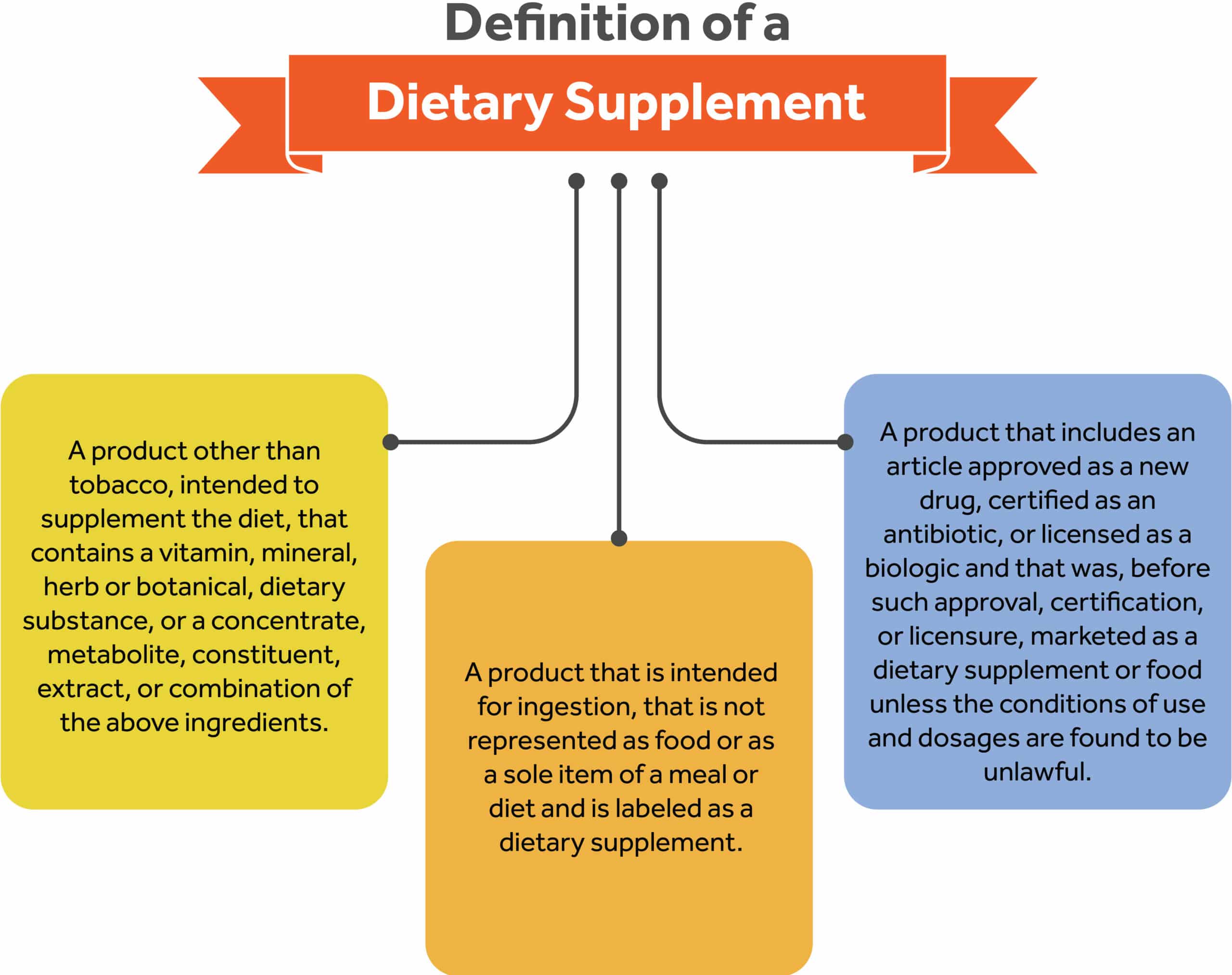

A dietary supplement is a product that is intended to supplement the diet, and that contains one or more of the following: vitamins, minerals, herbs or other botanicals, amino acids, or other dietary substances for use by a human to supplement their diet by increasing their total dietary intake or concentrates, metabolites, constituents, extracts, or combinations of these ingredients.14 A more comprehensive definition can be found below15:

A product other than tobacco, intended to supplement the diet that contains a vitamin, mineral, herb or botanical, dietary substance, or a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract, or combination of the above ingredients.

- A product that is intended for ingestion, that is not represented as food or as a sole item of a meal or diet and is labeled as a dietary supplement.

- A product that includes an article approved as a new drug, certified as an antibiotic, or licensed as a biologic and that was, before such approval, certification, or licensure, marketed as a dietary supplement or food unless the conditions of use and dosages are found to be unlawful.

- A product that excludes such articles which were not so marketed before approval unless found to be lawful. Deems a dietary supplement to be a food. Excludes a dietary supplement from the definition of the term “food additive.”

Dietary Supplement Regulation

The regulation of Dietary Supplements (DS) is overseen by two government agencies: the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The FDA is the major agency in the United States food supply that ensures food safety, monitoring, and inspection of animal products, sanitation, proper food labeling, food additives, genetically modified foods, and pesticides.16

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) regulates advertising, including infomercials, for dietary supplements.17 Both the FDA and FTC have the authority to take enforcement actions against dietary supplements and firms if they identify violations.

The FDA regulates dietary supplements under a different set of regulations than those covering conventional foods and drug products. In 1994, the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) was enacted to prohibit dietary supplement manufacturers and distributors from making false claims on supplement labels, to prohibit the manufacture and sale of adulterated dietary supplements, and categorized dietary supplements as food instead of drugs or dietary additives.15

However, many dietary supplements contain ingredients that have strong biological effects and can potentially conflict with a drug or medical condition.14 A more comprehensive list of the federal law set forth by the DSHEA is listed below:

- It is advised that a company that introduces a new DS must send a notification including safety information to the FDA 75 days before selling the supplement.18 This is not a requirement given that DS are classified as food products and not drugs.19 The FDA is not authorized to approve dietary supplements for safety and effectiveness before they are marketed. In many cases, firms can lawfully introduce dietary supplements to the market without even notifying FDA.19

- A DS label must contain the product name and a statement that it is a “dietary supplement” or equivalent term replacing “dietary” with the name or type of dietary ingredient in the product (e.g., “iron supplement” or “herbal supplement”), all ingredients must be declared, and the name, place of business of the manufacturer, packer, distributor, and contact information must be displayed.18

A supplement facts panel defines how ingredients must be listed on the label.18

The label must also include the disclaimer, “This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration.18 This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease,” because only a drug can legally make such a claim. 18

Manufacturers and retailers are not allowed to display product information or technical data sheets next to products. 18

A DS label is no longer allowed to list disease states or make specific health claims on DS labels but can make “structure/function” claims and those are not subject to premarket review and authorization by FDA.18

Dietary Supplement Labeling Claims

Among the claims that can be used on dietary supplement labels, there are three categories of claims defined by FDA regulations: health claims, structure/function claims, and nutrient content claims.

Health Claims

Health claims describe the relationship between a substance (whether a food, food component or dietary ingredient) and a disease or health-related condition.18 A health claim can mention a disease state as long as it has met the significant scientific agreement standard of the FDA and can exist on foods and dietary supplements.20, 21

An example of a health claim is “soluble fiber from foods such as oat bran, as part of a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol, may reduce the risk of heart disease.” All health claims, whether authorized or qualified, require pre-market review by the FDA.20, 21

Authorized Health Claims

Authorized health claims must be supported by a significant scientific agreement that the proclaimed benefit of a food or food component on a disease or health-related condition is true.20, 21

An example of an authorized health claim is “low-fat diets rich in fiber-containing grain products, fruits and vegetables may reduce the risk of some types of cancer, a disease associated with many factors.”

Qualified Health Claims

Qualified health claims have significant scientific agreement supporting the claim however there is insufficient evidence to approve them as health claims.20, 21 An example of a qualified health claim is “consumption of omega-3 fatty acids may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease.”

Structure-Function Claims

Structure-function claims describe the role of a nutrient or dietary ingredient intended to affect the normal structure or function of the human body.20, 21 In addition, they may characterize how a nutrient or dietary ingredient acts to maintain such structure or function, for example, “calcium builds strong bones,” “fiber maintains bowel regularity,” or “antioxidants maintain cell integrity.”

Structure/function claims for conventional foods focus on effects derived from nutritive value, while structure/function claims for dietary supplements may focus on non-nutritive as well as nutritive effects.20, 21

FDA does not require conventional food manufacturers to notify FDA about their structure/function claims, and disclaimers are not required for claims on conventional foods.20, 21

Nutrient Content Claims

Nutrient content claims describe the level of a nutrient in food using terms such as free, high, and low, or they compare the level of a nutrient in a food to that of another food, using terms such as more, reduced, and light.20, 21 Nutrient content claims have been authorized by FDA and are made following FDA’s authorizing regulations.20, 21 An example of a nutrient content claim is a package of muffins that carries the claim “Low in Fat.”

Vitamin and Mineral Supplements

Supplements Versus Whole Foods

The skyrocketing sales and use of supplements in the United States continue to expand at a rapid pace. Some of the reasons associated with supplement use in the American population are speculated to be related to the growing interest in food and nutrition in the maintenance of health and widespread availability.22, 23

In fact, in the US, over 50% of adults declare supplement use, and in some studies, almost 40% had taken dietary supplements during the previous 30 days when they were questioned.22, 23

In general, the scientific community and medical providers have come to the consensus that diversifying intake of whole foods is better assimilated and more effective at treating deficiencies than supplements alone. The most notable observed benefits in whole foods compared to supplements are:

- Food bioavailability: whole foods including dairy, fruits, and vegetables offer greater nutrient density and micronutrient bioavailability compared to supplements. In simple terms, the bioavailability of vitamins in food means how much of a micronutrient is absorbed or made available to the body when consumed in the diet.24 In contrast, supplements and fortified foods typically contain much higher amounts of nutrients than whole foods, but it is not guaranteed that the body can absorb them and put them all to use.

- Essential fiber: a big proportion of whole foods such as cereals, fruits, and vegetables contain dietary fiber. While dietary fiber is derived from one of the macronutrients, it is not considered an essential macronutrient.25 Given the increasing prevalence of Americans with suboptimal intakes of fiber, the Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee acknowledges that fiber is a “nutrient of a public health concern due to the adverse health outcomes relative to its underconsumption.”10 When comparing supplement use to whole food consumption, supplements only provide an isolated source of the nutrient, and generally lack the fiber component necessary to meet the recommended daily intakes of fiber and observable health benefits that whole foods offer.

- Antioxidants and phytochemicals: these compounds are naturally occurring in whole foods such as fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and legumes and play an important role in the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases. The main role of antioxidants and phytochemicals is to scavenge free radicals in the body and act as anti-inflammatory agents, ultimately protecting against cancer, aging, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and neurodegenerative diseases.26

Target Population

The literature has made it clear that the consumers of dietary supplements are mostly middle-aged and older adults. As it appears, the routine intake of supplements by healthy populations is not strictly tied to a particular disease state or micronutrient deficiency but rather taken for preventative reasons. And for this reason, people with healthier diets and lifestyles make it hard to study and determine whether vitamin and mineral supplementation offer the supposed benefits.

To this point, the literature continues to show that the taking of vitamin and mineral supplements by healthy people neither lowers their risk of cardiovascular diseases nor prevents the development of malignancies.27

With some exceptions, there is recognized evidence that omega-3 fatty acids lower blood triglycerides, but the extent that taking them prevents heart disease is ambiguous.27 Similar examples follow this pattern for supplements intended to aid in weight loss and cancer prevention.

Populations Who May Benefit from Supplements

Certain special populations may benefit from specific supplementation. While it exceeds the Trainer Academy Personal Trainer Scope of Practice to recommend supplements to these populations, individuals in the following categories can benefit from certain supplementation protocols:

Toxicity and Safety

Toxicity

While it is difficult for food to cause nutrient imbalances or toxicities, supplements can easily lead to toxicity and adverse effects when routinely ingested in higher doses. The extent of supplement toxicity in the United States is unknown, but many adverse events are reported each year from overconsuming vitamins, minerals, essential oils, herbs, and other supplements.

Several committees, for example, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and Institute of Medicine (IOM) have set tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) to prevent micronutrient toxicities. The DRI Tolerable Upper Intake Levels define the highest intakes of dietary vitamins and minerals that appear safe for most healthy people.9

This parameter is different from the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR), which assesses the average daily nutrient intake that is estimated to meet the requirements of 50% of the healthy individuals in a group.9

In other words, the EAR assesses nutrient adequacy in groups and ULs prevent the risk of adverse effects from excessive nutrient intakes.

Dietary supplement toxicity is the umbrella term that encompasses vitamin overdosage, vitamin overload, and hypervitaminosis. Vitamin overdosage and overload are observed with every vitamin and produce high blood and tissue levels of the vitamin itself. Vitamin overdosage is obtained only upon administration of high doses of a vitamin, while vitamin overload may originate from a variety of factors.28

Hypervitaminosis is a condition of abnormally high blood levels of a specific vitamin, generally, vitamin A and D, that either manifests as acute or chronic and is characterized by specific symptomatology.28

Megadoses of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) can easily cause toxicity and should be taken with caution, particularly for individuals with medical conditions and pregnant women. Vitamin A toxicity is most notable and can cause nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness, and blurred vision.29

While water-soluble vitamin toxicity is rare, folic acid overdose is common and can cause adverse events when taken in excessive doses, generally manifesting as reversible neurological complications.30 Furthermore, some people may experience adverse effects from too much calcium or iron. In the case of iron toxicity, observable side effects include coma or low blood pressure, which can sometimes be fatal.

Iron overdoses can have long-term consequences on the intestines and liver, including intestinal scarring and liver failure.31, 32 Calcium toxicity is not as fatal as iron, but high calcium levels can cause serious heart rhythm disturbances, as well as kidney stones and damage to kidney function. Long-term overuse is often more serious than a single overdose.

Safety

Proving supplement safety is one of the many risks that the FDA bears under the DSHEA. In 2006, the Dietary Supplement and Nonprescription Drug Consumer Protection Act was signed into law, requiring mandatory reporting by manufacturers and retailers of known serious adverse events (AEs) related to dietary supplements and over-the-counter (OTC) medications.33 Serious adverse events related to dietary supplements and drugs include life-threatening events, incapacitation, hospitalization, birth defects, and death.

The adverse effects associated with dietary supplements vary consistently in the literature. The most common supplements with health and safety concerns are those used for weight loss, performance enhancement (ergogenic aids), and sexual dysfunction.34

According to the FDA, these supplements have the highest risk of contamination and adulteration with unapproved dietary ingredients and pharmaceutical drugs.35 A nine-year report published by the CDC found that among young adults aged 20-34, the most common supplements causing adverse events were weight loss and energy (ergogenic aids) and the most common symptoms were tachycardia, chest pain, and palpitations.36

For adults 65 and older, adverse events were mostly attributed to choking on micronutrient pills.36 Up to date, only two dietary supplements have been banned by the FDA, Ephedra sinica in 2004, and dimethylamylamine (DMAA) in 2013, as being linked to cardiovascular toxicity and death.35

More recently, the FDA announced that N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), used for chronic respiratory conditions, fertility, and brain health, is no longer included in the definition of a dietary supplement.37

Reporting Adverse Effects

The same year that the DSHEA was enacted, the National Institutes of Health founded the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS).41 The purpose of this entity is to increase awareness of dietary supplements, provide credible information to the public, and alert the public on current warnings and recalls as well as consumer tips for buying and taking dietary supplements safely.41

On the government website, consumers can find basic consumer information and a Dietary Supplement Label Database of dietary supplements used in the United States.41 This database was developed to provide specific information on the ingredients in a supplement, technical data sheets about dietary supplements and herbs, and FDA warnings.41

In the event of a suspected serious health-related reaction or illness associated with a dietary supplement, alert a medical provider or healthcare professional knowledgeable in nutrition. In addition, reporting adverse reactions to supplements directly to the FDA via its hotline or website (FDA MedWatch) is highly recommended. Adverse event reports are forwarded to the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, where they are further evaluated by qualified reviewers.

Common General Health Supplements

Multivitamin/Mineral Supplements

Multivitamin/mineral Supplements (MVM) have gained public attention over the years and are considered one of the most popular supplements on the market. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that between 2003 and 2006, the most commonly used supplements were multivitamins and multiminerals with at least half of the men and women 50 years of age or older regularly consuming them.38

In the years 2005–2012, the ten most popular of these, in order of decreasing prevalence of use, were vitamin D, vitamin C, calcium, cobalamin, vitamin E, folic acid, pyridoxine, niacin, vitamin A, and riboflavin.38

To date, there is no clear unanimity suggesting that MVMs help prevent chronic disease. In general, multivitamins from reputable sources without add-ons test free from contamination, and taking a daily dose of a basic MVM is unlikely to pose a health risk for most people.39

However, caution must be taken if consuming fortified foods and beverages along with dietary supplements. Reading the Supplement Facts label and percent daily value (% DV) to see what proportion of daily allotment one gets from taking a vitamin is generally considered safe to prevent toxicity.39

The biggest contraindication in MVMs use is that they have no standard scientific, regulatory, or marketplace definitions. Manufacturers determine the combinations and levels of vitamins, minerals, and other ingredients in them and therefore they have no standard regulations as to what nutrients they must contain or in what amounts.39

Furthermore, the definition of MVMs and evaluation of potential health effects varies greatly in the scientific literature. This concern and the fact that many dietary supplements are not labeled as MVMs even though they contain a variety of vitamins and minerals further complicates the study of MVMs.

Botanical and Herbal Supplements

Botanical and herbal supplements are dietary supplements that are increasingly popular among the public. In particular, athletes’ use of herbal supplements is higher than that of the general public, and reasons for intake range from performance enhancement to immune function improvement to the prevention of illness or healing of injuries.40

However, regular ingestion of herbal supplements also raises toxicity and safety concerns among the scientific community. The reasons why controversies related to herbal dietary supplement intake exist include limitations in scientific evidence, premarket approval, and FDA regulation.

In general, most of the common herbs used in the United States do not pose a risk for a drug-nutrient interaction (DNI).34 Out of the most commonly used herbal supplements, St. John’s wort is the most problematic and has been shown to reduce the efficacy of many drugs, including antiretrovirals for HIV, antirejection medications for organ transplants, oral contraceptives, cardiac medications, chemotherapy, and cholesterol medications.34

Two other herbs have been shown to have a high risk for DNI, including goldenseal and black pepper in the supplemental form.34

Common Legal Performance Enhancing Supplements

Performance-enhancing substances (PES) are any substances taken in non-pharmacologic doses specifically used to improve athletic performance and alter one’s appearance toward a more muscular and lean body. When surveyed, individuals reported using PES to improve physical appearance, increase muscle mass, optimize general health, and help meet physical demands on their bodies.42

Over the years, the literature has shown that PES in the athletic population has steadily increased and has been estimated internationally at 37% to 89%, with greater frequencies being reported among elite and older athletes.43

Among college athletes and nonathletes, prevalence rates of PES are also relatively high. In a study from 2008, at least 46% of male nonathletes and 56% of male athletes, as well as 25% of female nonathletes and 30% of female athletes, were using these substances.44

More recently, PES has become increasingly popular among adolescents and young adults and there is a growing trend of using PES as cognitive function enhancements for academic performance, attention, and memory, specifically through the use of neuroactive substances.45

In particular, a prospective cohort study from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, Waves I to IV (1994–2008) identified 16.1 % of young men and 1.2% of young women from a sample of 12,133 young adults aged 18 to 26 years who used legal PES in the past year.46

Along with the increased usage of these products, there is an ever-growing cause for concern about not only their effectiveness but also safety. Since PES are mostly unregulated by the FDA and clinical trials lack data and regulation, inconsistencies exist on the legal status of PES in federal and state laws in the United States and medical outcomes associated with their use.

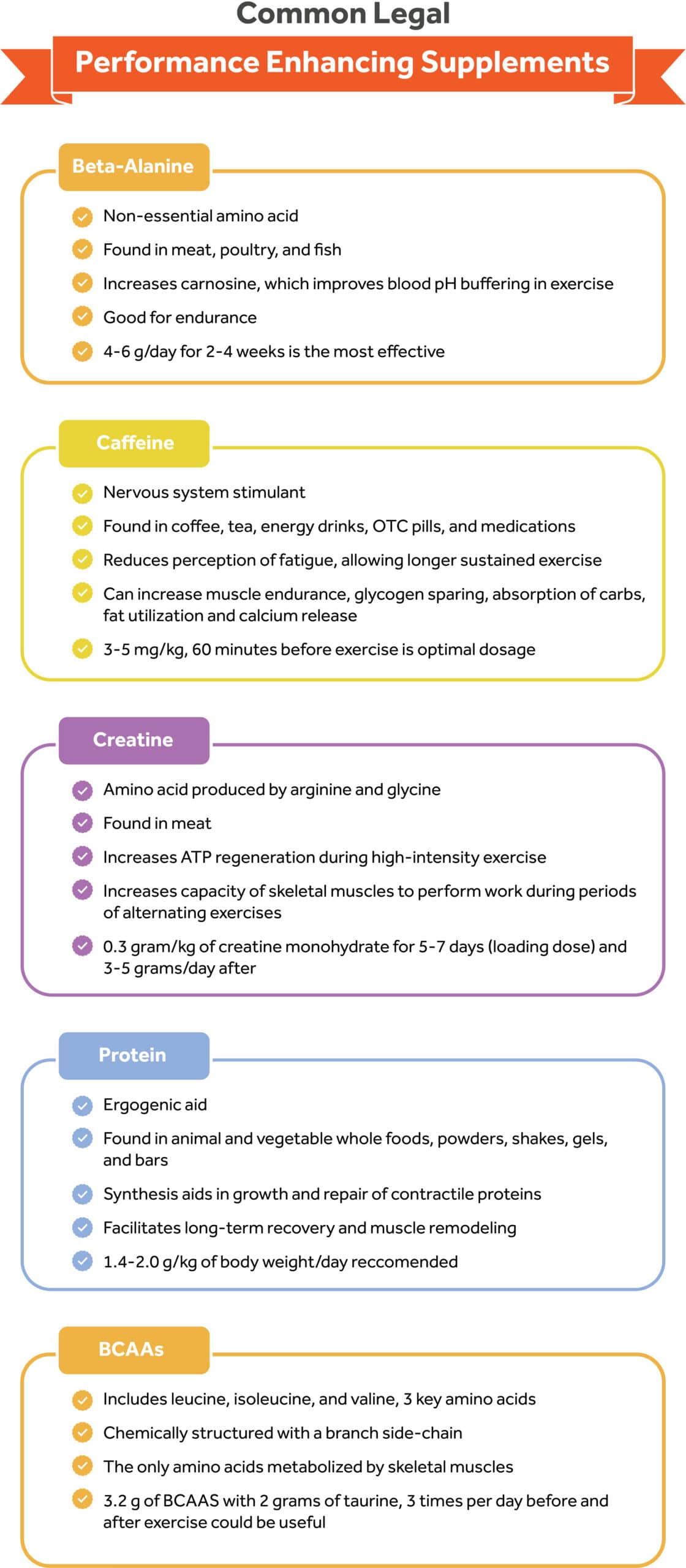

Legal PES can be classified according to the constituent ingredients, and the timing of the training. The most common legal PES that will be discussed in this chapter include: creatine, caffeine, protein and branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), and beta-alanine.

Pre-Workout Supplements

Pre-workouts are supplements ingested before an exercise session or sporting event intended to increase mental focus, endurance, blood flow, strength, power, aerobic and anaerobic capacity, or overall perceived increase in energy level.

While a small amount of evidence exists for potential benefits when consuming a pre-workout supplement, inconsistencies within the literature remain when considering the specific dosages, populations, and types of activities performed.

According to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine, the ingredients mentioned below are common pre-workout supplements that have been regarded as safe and have strong evidence to support efficacy.

Beta-Alanine

Beta-alanine (β-alanine) is a non-essential amino acid commonly found in meat, poultry, and fish. During exercise, the formation of lactic acid is likely to result if insufficient glucose is present in the body to be metabolized for energy.

This metabolic reaction lowers muscle pH levels and reduces the muscles’ ability to contract, causing fatigue.47, 48 The purpose of supplementing beta-alanine is to increase concentrations of carnosine, a proton that improves muscles and blood pH buffering capacity during high-intensity exercise, and reduces overall fatigue.

In addition, beta-alanine can increase time to exhaustion,49 muscular endurance,50, 51 anaerobic capacity,48 and lean mass,52 ultimately enhancing training capacity. The optimal dosage is set between 4 to 6 g/day for 2–4 weeks and is most effective when complimenting high-intensity exercises lasting 1–4 minutes, such as high-intensity interval training (HIIT) or short sprints.47

The only reported side effect is paraesthesia (i.e., tingling) but studies indicate this can be attenuated by using divided lower doses (1.6 g) or using a sustained-release formula.47 At usual doses, beta-alanine appears to be safe for most healthy populations except for pregnant or breastfeeding individuals.

Caffeine

Caffeine is a central nervous system stimulant ubiquitously found in a variety of food and beverages such as coffee, tea, energy drinks, pre-workout supplements, over-the-counter diet pills, and medications. The ergogenic benefits of caffeine as a pre-workout have been documented.

Caffeine can reduce the perception of fatigue and allow exercise to be sustained for longer.53 In addition, caffeine can increase muscular endurance, glycogen sparing during exercise, intestinal absorption of carbohydrates, fat utilization, and calcium release.54

The optimal dose of caffeine ranges from 3 to 6 mg/kg, approximately 60 min before exercise, and is most effective for high-performance athlete improvements.54

The FDA established that 400 mg/day of caffeine is a safe amount of daily consumption for the general population.55 Higher doses of caffeine (9–13 mg/kg) do not result in an additional improvement in physical performance and are associated with a high incidence of side effects such as nausea, anxiety, and insomnia.56

The most commonly reported side effects of caffeine are tachycardia, heart palpitations, anxiety, headaches, and insomnia quality, and its use should be discontinued for individuals taking stimulant medications, anticoagulants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and quinolone antibiotics.54, 57, 58, 59

Creatine

Creatine, usually sold as creatine monohydrate is an amino acid produced by arginine and glycine, two non-essential amino acids. Approximately 2 grams of creatinine can be obtained daily from dietary sources such as meat and fish.60

Creatine supplementations elevate muscle creatinine levels and increase ATP regeneration by delaying the onset of muscle fatigue during high-intensity exercise and increasing the capacity of the skeletal muscle to perform work during periods of alternating exercise.61 The classical loading protocol consists of ingestion of 0.3 grams/kg/day of CM for 5 – 7 days (e.g., ≃5 grams taken four times per day) and 3–5 grams/day thereafter.62, 63

The safe limit is 30 grams of creatine within a day. Some loading protocols consist of loading creatine with 20-30 grams of creatine 5-7 days in a row, and then progressing to the 3-5 grams/day after.

The performance benefit of creatine supplementation has been primarily observed in short-duration, maximum-intensity resistance training, and strength training.64

Conflicting evidence appears in studies assessing the effect of creatine on endurance sports. In healthy individuals, creatine supplements are generally safe when taken both short and long term and no adverse effects from consuming recommended doses of creatine supplements have been documented.65

Since supplementation has the potential to raise creatinine levels and mimic kidney disease, creatine supplementation should not be used by individuals and athletes with pre-existing kidney disease or those with a potential risk for kidney dysfunction.66

Post-Workout Supplements

Protein

Protein as an ergogenic aid can be found in many foods, from animal and vegetable whole foods, powders, shakes, gels, and bars. Powdered protein can come from various sources, including eggs, milk (e.g., casein, whey), and plants (e.g., soybeans, peas, hemp). Some protein powders can contain protein from multiple sources (e.g., plant-derived).

The ergogenic effects of protein as a post-workout supplement have been well documented in the literature, claiming that its purpose is to provide sufficient “building blocks” for muscle and lean tissue growth after the body’s resistance to acute high-intensity training.

As a result, damage to contractile proteins and muscle soreness occurs, which can last for several days and may impair muscle function. In these circumstances, an adequate intake of protein may increase synthesis, whereas its absence increases the rates of protein degradation resulting in a negative net protein balance.

In theory, protein supplementation stimulates protein synthesis that aids in the growth and repair of contractile proteins, thereby facilitating long-term recovery and muscle remodeling.67, 68, 69, 70

According to the American College of Sports Nutrition, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and Dietitians of Canada, there is a lack of evidence from well-controlled studies that protein supplementation directly improves athletic performance.71

However, protein supplementation in the presence of adequate carbohydrate intake during the recovery period may delay muscle damage and soreness.71 The extent to which protein supplementation improves resistance in athletes is contingent on a variety of factors, including intensity and duration of the training, individual age, dietary energy intake, and quality of protein intake.71, 72

For athletic individuals engaging in strenuous exercise that seek to build and maintain muscle mass, the International Society of Sports Nutrition recommends an overall daily protein intake of 1.4–2.0 g/kg of body weight/day.72 For resistance-trained individuals higher protein intakes (>3.0 g/kg/d) may have positive effects on body composition (i.e., promote loss of fat mass). These protein doses should ideally be evenly distributed, every 3–4 h, across the day.72

In addition, it is advised to take protein supplements with caution as they are considered dietary supplements with no FDA approval for safety or effectiveness. In particular, protein supplements often contain processed materials and lack other essential nutrients required for the sustenance of a healthy lifestyle.

It is suggested that the required protein intake be obtained from natural whole food sources and protein supplementation should be resorted to only if the protein is insufficiently available in the normal diet.

Protein supplements appear to be safe for the general population, and to date, there is limited information available concerning the possible side effects of long-term supplementation. To date, the only adverse effects reported come from protein powders and claim symptoms of gastrointestinal discomfort, increased risk of weight gain and uncontrolled blood glucose from added sugars and calories, and contamination with non-protein ingredients.

A more recent report found that many protein powders sold recently contained heavy metals (lead, arsenic, cadmium, and mercury), bisphenol-A (BPA, which is used to make plastic), pesticides, and other contaminants with links to cancer and other health condition.73

Reading the nutrition and ingredient labels and consulting with a physician, sports dietitian, or athletic staff beforehand is recommended to prevent contamination with banned substances that are not listed on the label.

Branched Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs)

Branched chain amino acids (BCAAs) include leucine, isoleucine, and valine, three essential amino acids that are chemically structured with a branch side-chain that form one-third of the total protein in the body74 and are the only amino acids metabolized by the skeletal muscles.75 BCAAs must be obtained from external sources such as protein foods like chicken, red meat, fish, and eggs because the body can’t produce them.

The three BCAAs are unique among the EAAs for their roles in protein metabolism, neural function, and blood glucose and insulin regulation.72 In the last decade, consumption of BCAAs in the form of dietary supplements has increased among recreational exercisers and athletes based on the potentially efficacious effects on reduction in protein degradation, muscle damage, feelings of soreness, and fatigue after ingestion post-exercise.76, 77, 78 A combination of 3.2 g BCAA and 2.0 g taurine, three times a day, for 2 weeks before and 3 days after exercise was a useful strategy for reducing delayed muscle soreness and muscle damage.79

While short-term intake of leucine has the potential to improve protein synthesis, long-term trials do not support BCAAS as useful performance enhancers that accelerate the repair of muscle damage after exercise.72

In addition, caution must be taken when ingesting high intakes of leucine, as it can potentially disrupt the normal action of insulin and dysregulate blood glucose, making increased BCAA concentrations and their metabolites responsible for insulin resistance and complications associated with diabetes.80, 81

The excess of BCAA may lower brain uptake of other neutral amino acids, such as phenylalanine, tyrosine, HIS, and tryptophan (TRP), which are precursors of dopamine, norepinephrine, histamine, and serotonin.82

Ethical, Legal, and Health Issues with

Illegal Performance-Enhancing Drugs

Epidemiology and Use

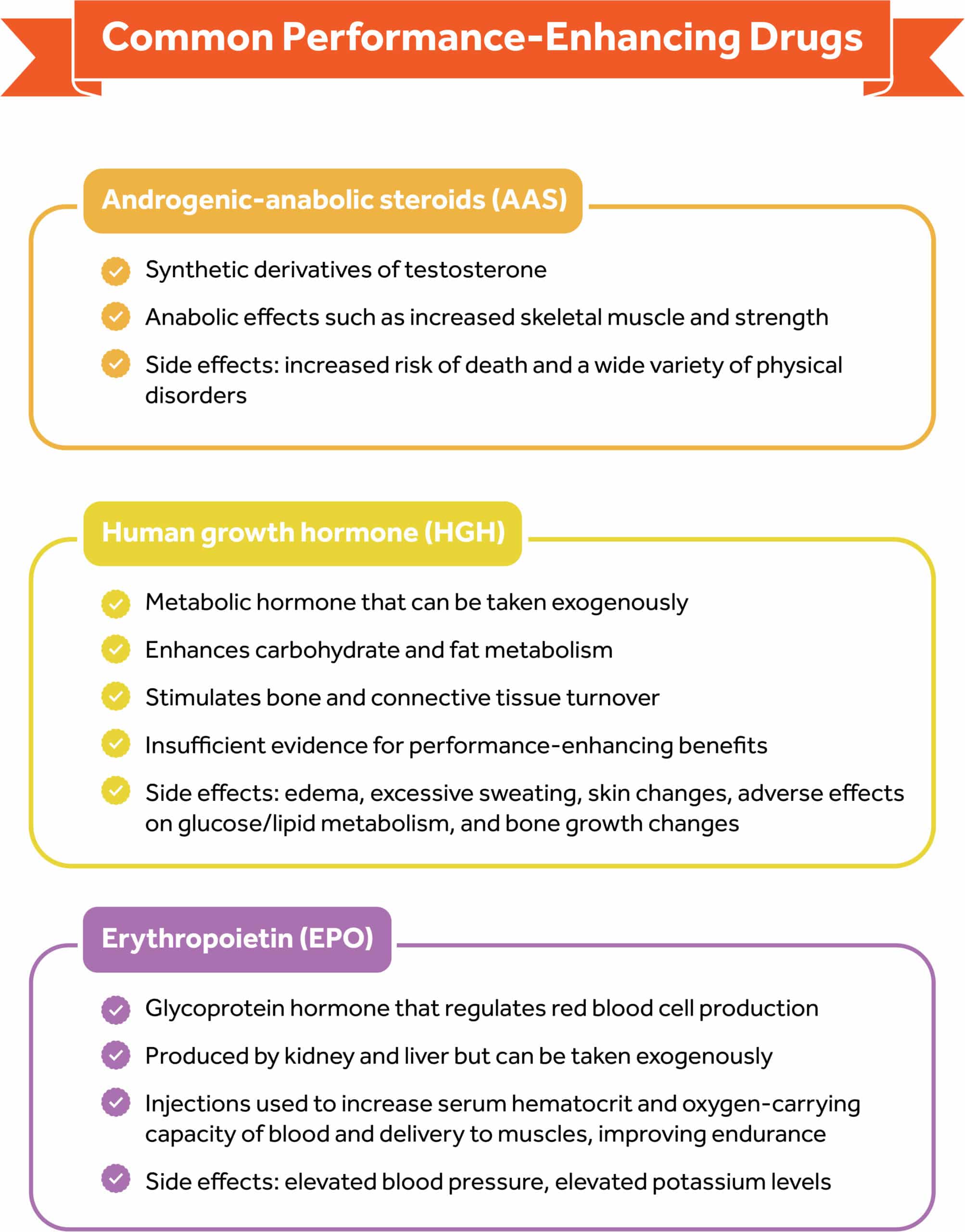

Performance-Enhancing Drugs (PED) are pharmacological substances that are commonly used by competitive, professional, Olympic athletes, and non-athlete weightlifters to improve performance, muscle recovery, and prevent nutritional deficiencies.

The most common PEDs include anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS), beta 2 agonists, peptide hormones, diuretics, cannabinoids, blood doping, narcotics, beta-blockers, and corticosteroids, human growth hormone, erythropoietin, diuretics, and stimulants.

The use and prevalence of PEDs use have increased dramatically over the past decade. To date, it has been estimated that there are at least 3 million PED users in America, which puts PED use on a scale similar to commonly encountered diseases such as Type 1 Diabetes and HIV.83, 84

Although steroid use is widespread in many Western countries, the United States appears to be the leading country in AAS use.83, 84 In addition, a systematic review that sampled between 1976 and 2019 from 35 countries estimated that the rates of doping prevalence in competitive sports ranged between 0 and 73%, with most falling under 5%.85

The vast majority of PED users are not athletes but rather nonathlete weightlifters, and the adverse health effects of PED use are greatly underappreciated. Furthermore, the individuals who are particularly vulnerable for use of performance-enhancing substances are adolescents. Among athletes who use PEDs, those who play football, baseball, and basketball, who wrestle, and who are involved in gymnastics and weight training are at increased risk.84

Purpose and Adverse Effects

Androgenic-Anabolic Steroids

Androgenic-anabolic steroids (AAS) are synthetic derivatives of the male hormone testosterone. Testosterone is a male sex hormone and the most common androgen that helps promote the development and maintenance of male sex characteristics.

Androgens also have anabolic effects such as an increase in skeletal muscle mass and strength. Athletes and nonathlete weightlifters take AASs orally, transdermally, or by intramuscular injection; however, the most popular mode is the intramuscular route.34

Oral preparations have a short half-life and are taken daily, whereas injectable androgens are typically used weekly or biweekly.34

The primary effects of AAS usage include34 :

- Muscle fiber hypertrophy

- Increased tissue net oxygen delivery

- Increased bone mineral density

- Increased blood cell production

- Decreased body fat

- Increase heart, liver, and kidney size

- Vocal cord changes

- Increased libido

- Mood and motivation

The main effects of short- and long-term AAS use that athletes most often self-report are an increase in sexual drive, the occurrence of acne vulgaris, increased body hair, and an increment of aggressive behavior.34

Adverse effects of PEDs use have also been reported in the literature, particularly, associations with increased risk of death and a wide variety of cardiovascular, psychiatric, metabolic, endocrine, neurologic, infectious, hepatic, renal, and musculoskeletal disorders.83

These drugs have also been implicated in stroke, seizures, and such adverse psychiatric conditions as anxiety, mood changes, and autonomic hyperactivity.86 “Steroid rage” has been cited as a cause of aberrant behavior in some adolescent males.87

It also is associated with other high-risk behaviors, such as the use of other illicit drugs, reduced involvement in school, poor academic performance, engaging in unprotected sex, aggressive and criminal behavior, suicidal ideation, and attempted suicide.34

Human Growth Hormone

Human growth hormone (HGH) is a naturally occurring metabolic hormone secreted by the pituitary gland. In healthy adults, HGH enhances carbohydrate and fat metabolism, helps to maintain sodium balance, and stimulates bone and connective tissue turnover.34

In addition, HGH regulates protein through anabolic effects including protein oxidation sparing, increasing lean body mass, and decreasing fat mass.34 Despite these physiological effects, there is not enough evidence to suggest that HGH administration enhances physical performance or has adverse effects on HGH.

Therefore, most of the information is anecdotal, and these reports are often confounded by concurrent use of other PEDs, especially AASs. The potential side effects include edema, excessive sweating, skin changes, darkening of moles, adverse effects on glucose and lipid metabolism, and the growth of bones as evidenced by the development of a protruding jaw and boxy forehead.34, 83

Erythropoietin

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a glycoprotein hormone that regulates red cell production and is produced by both the kidney and the liver. In adults, the kidneys are the dominant source of circulating erythropoietin, although the liver is an important contributor to erythropoietin production in the fetal and perinatal periods.

EPO injections are used in the athletic population to increase the serum hematocrit and oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and delivery to the muscle and thereby improving endurance.34

While EPO use as an ergogenic aid is popular in endurance sports, such as distance running, cycling, and triathlons, it is difficult to detect because it is a hormone produced by the kidneys.

The usage of EPO augments the risk of thrombosis, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events (including myocardial infarction and stroke), and hypertension.34 EPO also can cause elevated blood pressure or elevated potassium levels.34

Legality Issues and Regulations

The use of PEDs is banned in major sports organizations that regulate sporting competitions to protect the health and well-being of athletes and ensure fair play in Olympic sports. In competitive sports, the term doping is used to define the use of banned athletic performance-enhancing drugs by athletic competitors.

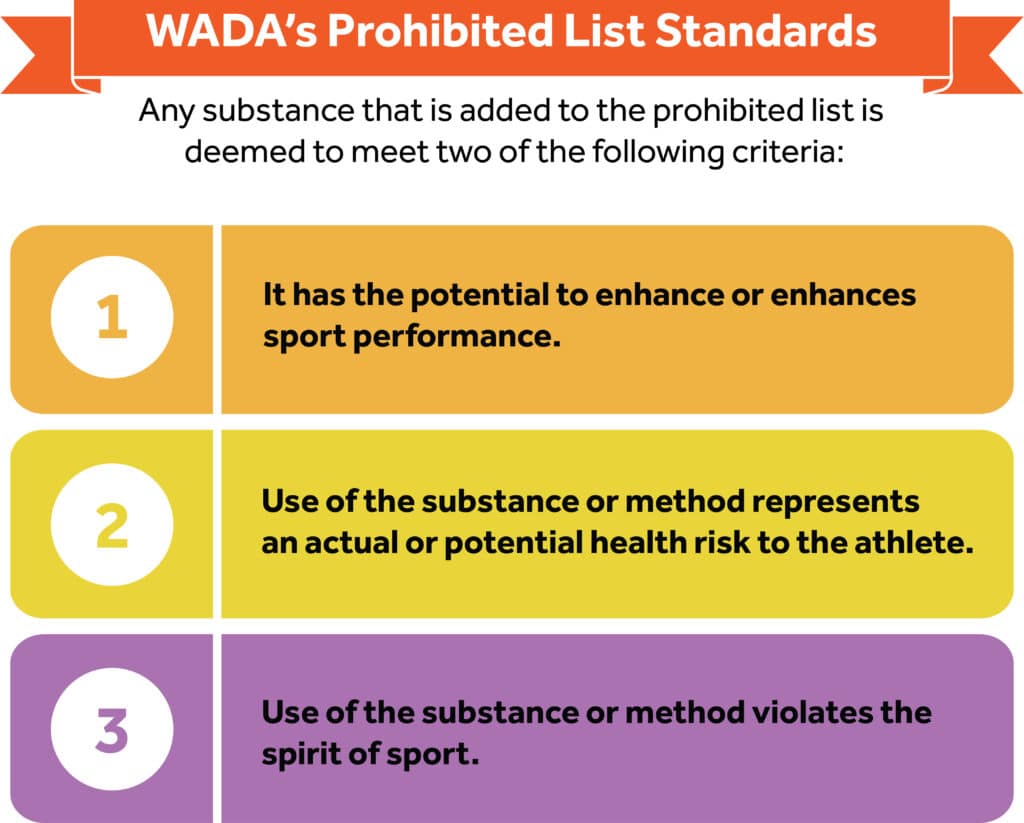

To prevent that, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) is an international agency that oversees the implementation of the anti-doping policies in all sports worldwide and maintains a list of substances (drugs, supplements, etc,) that are banned from use in all sports at all times, banned from use during competition, or banned in specific sports.88

The WADA’s Anti-Doping Program is based on the WADA Code, a universal core document that contains anti-doping policies, and rules and regulations for best practices in international and national anti-doping programs.89 It works in conjunction with eight mandatory international standards and 12 non-mandatory guidelines.89

The WADA’s Prohibited List is a mandatory International Standard that gets updated at least annually, with the new list taking effect on January 1st each year.90 Any substance that is added to the prohibited list is deemed to meet two of the following criteria90:

- It has the potential to enhance or enhances sport performance

- Use of the substance or method represents an actual or potential health risk to the athlete

- Use of the substance or method violates the spirit of sport

Additionally, the list is divided into the substances and methods that are prohibited at all times, or prohibited only in competition.90 Those substances banned at all times would include (but are not limited to) hormones, anabolics, EPO, beta-2 agonists, masking agents, and diuretics.90

Those substances prohibited only in competition would include but not be limited to stimulants, marijuana, narcotics, and glucocorticosteroids.90 Also banned at all times are methods such as blood transfusion or manipulation, or intravenous injections in some situations.90

It is important to remember that not all substances and methods are named on the Prohibited List.90 Even if not expressly named, a substance and method can be deemed prohibited if90:

- It is not currently approved by any governmental regulatory health authority for human therapeutic use (e.g. drugs under pre-clinical or clinical development or discontinued, designer drugs, substances approved only for veterinary use), or

- It has a similar chemical structure or similar biological effect(s).

Above all, athletes are responsible for knowing what substances and methods are considered banned on the Prohibited List.

Under World Athletics Rules, the presence of a prohibited substance in an athlete’s sample, the use of a prohibited substance, and the prohibited method all constitute a doping offense.

It is important that those who work with athletes acquaint themselves with WADA’s List of Prohibited Substances and Methods.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) also bans the use of PEDs and recreational drugs to protect the health of college athletes and ensure fair play.91 The NCAA tests for steroids, peptide hormones, and masking agents year-round and tests for stimulants and recreational drugs during championships.91

Member schools also may test for these substances as part of their athletics department drug-deterrence programs.91 A positive drug test will result in loss of eligibility and suspension from the sport, including the risk of negatively impacting health.91

Summary

The popularity of dietary supplements and even performance-enhancing drugs mean that fitness professionals routinely discuss them with clients in the context of health and fitness.

While making supplement recommendations is outside the Trainer Academy Scope of Practice, certified trainers can discuss research on the efficacy and safety of supplements, as long as they do not prescribe them to the client.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Micronutrient facts. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/micronutrient-malnutrition/micronutrients/index.html. Published February 1, 2022. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- Muñoz García M, Pérez Menéndez-Conde C, Bermejo Vicedo T. Avances en el conocimiento del uso de micronutrientes en nutrición artificial [Advances in the knowledge of the use of micronutrients in artificial nutrition]. Nutr Hosp. 2011;26(1):37-47

- Stipanuk, M. H. Biochemical, physiological, & molecular aspects of human nutrition. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

- Shenkin A. Micronutrients in health and disease. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(971):559-567. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2006.047670

- Rizvi S, Raza ST, Ahmed F, Ahmad A, Abbas S, Mahdi F. The role of vitamin e in human health and some diseases. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2014;14(2):e157-e165.

- Demling RH, DeBiasse MA. Micronutrients in critical illness [published correction appears in Crit Care Clin 1996 Oct;12(4): xi]. Crit Care Clin. 1995;11(3):651-673.

- Sizer FS, Whitney E. Nutrition Concepts & Controversies. 13th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Co; 2014

- Escott-Stump S. Nutrition & Diagnosis-Related Care. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2022.

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Nutrient Recommendations: Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI). Available at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/Health_Information/Dietary_Reference_Intakes.aspx. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 2020. 9th Edition. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov

- National Institutes of Health. Vitamin D. Available at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/ Published February 11, 2016. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- Schürks M, Glynn RJ, Rist PM, Tzourio C, Kurth T. Effects of vitamin E on stroke subtypes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2010;341:c5702. Published 2010 Nov 4. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.c5702

- National Institutes of Health. Vitamin C Fact Sheet for Professionals. Available at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminC-HealthProfessional/. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Dietary Supplements. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/dietary-supplements. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- S.784 – 103rd Congress (1993-1994): Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. (1994, October 25). http://www.congress.gov/

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Basics. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/fda-basics/what-does-fda-regulate. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- U.S. Federal Trade Commission. What the FTC Does. Available at: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/media-resources/what-ftc-does. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- Dickinson A. History and overview of DSHEA. Fitoterapia. 2011;82(1):5-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2010.09.001

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Information for Consumers Using Dietary Supplements. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements/information-consumers-using-dietary-supplements. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Label Claims for Conventional Foods and Dietary Supplements. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/label-claims-conventional-foods-and-dietary-supplements.Accessed September 26, 2022.

- Turner RE, Degnan FH, Archer DL. Label claims for foods and supplements: a review of the regulations. Nutr Clin Pract. 2005;20(1):21-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/011542650502000121

- Chen F., Du M., Blumberg J.B., Chui K.K.H., Ruan M., Rogers G., Shan Z., Zeng L., Zhang F.F. Association among dietary supplement use, nutrient intake, and mortality among U.S. adults: A cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019;170:604–613. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-2478.

- Costa J.G., Vidovic B., Saraiva N., Costa M.D.C., Del Favero G., Marko D., Oliveira N.G., Fernandes A.S. Contaminants: A dark side of food supplements? Free. Radic. Res. 2019;53:1113–1135. https://doi.org/10.1080/10715762.2019.1636045.

- Melse-Boonstra A. Bioavailability of Micronutrients From Nutrient-Dense Whole Foods: Zooming in on Dairy, Vegetables, and Fruits. Front Nutr. 2020;7:101. Published 2020 Jul 24. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2020.00101

- Kohn JB. Is Dietary Fiber Considered an Essential Nutrient? J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(2):360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2015.12.004

- Lobo V, Patil A, Phatak A, Chandra N. Free radicals, antioxidants, and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4(8):118-126. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-7847.70902

- Wierzejska RE. Dietary Supplements-For Whom? The Current State of Knowledge about the Health Effects of Selected Supplement Use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):8897. Published 2021 Aug 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18178897

- Roop JK. Hypervitaminosis—an emerging pathological condition. Int J Health Sci Res. 2018;8(10):280-288.

- Ross C, Vitamin A. In: Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements. Coates PM, Blackman MR, Cragg GM, Levine M, Moss J, White JD, editors. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2005. p. 713.

- Devnath GP, Kumaran S, Rajiv R, Shaha KK, Nagaraj A. Fatal Folic Acid Toxicity in Humans. J Forensic Sci. 2017;62(6):1668-1670. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13489

- Aronson JK. Vitamins. In: Aronson JK, ed. Meyler’s Side Effects of Drugs. 16th ed. Waltham, MA: Elsevier; 2016:435-438.

- Theobald JL, Mycyk MB. Iron and heavy metals. In: Walls RM, Hockberger RS, Gausche-Hill M, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 151.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Questions and Answers Regarding the Labeling of Dietary Supplements as Required by the Dietary Supplement and Nonprescription Drug Consumer Protection Act. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-questions-and-answers-regarding-labeling-dietary-supplements-required-dietary. Published September 2009. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- Mahan LK, Escott-Stump S. Krause’s Food, Nutrition, and Diet Therapy. 11th ed. W B Saunders; 2003.

- Tucker J, Fischer T, Upjohn L, Mazzera D, Kumar M. Unapproved Pharmaceutical Ingredients Included in Dietary Supplements Associated With US Food and Drug Administration Warnings [published correction appears in JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Nov 2;1(7):e185765]. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183337. Published 2018 Oct 5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3337

- Geller AI, Shehab N, Weidle NJ, et al. Emergency Department Visits for Adverse Events Related to Dietary Supplements. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(16):1531-1540. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1504267

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Releases Final Guidance on Enforcement Discretion for Certain NAC Products. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-releases-final-guidance-enforcement-discretion-certain-nac-products. Published August 1, 2022. Accessed September 26, 2022.

- Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Lentino CV, et al. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003-2006. J Nutr. 2011;141(2):261-266. doi:10.3945/jn.110.133025

- https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/vitamins-and-minerals

- Maughan RJ, Burke LM, Dvorak J, et al. IOC consensus statement: dietary supplements and the high-performance athlete. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(7):439-455. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099027

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. About ODS. Available at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/About/AboutODS/. Accessed September 26, 2022

- American College of Sports Medicine. Sports Supplements & Performance | The Athlete’s Kitchen. Available at: https://www.acsm.org/blog-detail/acsm-certified-blog/2021/08/31/sports-supplements-performance. Published August 31, 2021. Accessed September 26, 2022

- Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: Nutrition and Athletic Performance [published correction appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017 Jan;117(1):146]. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(3):501-528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2015.12.006

- Yusko DA, Buckman JF, White HR, Pandina RJ. Alcohol, tobacco, illicit drugs, and performance enhancers: a comparison of use by college student-athletes and non-athletes. J Am Coll Health. 2008;57(3):281–290

- Constantinou D, Aguiyi I. Use, Perceptions and Attitudes of Cognitive and Sports Performance Enhancing Substances Among University Students. Front Sports Act Living. 2022;4:744650. Published 2022 Apr 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.744650

- Ganson KT, Mitchison D, Murray SB, Nagata JM. Legal Performance-Enhancing Substances and Substance Use Problems Among Young Adults. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep;146(3):e20200409. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0409. PMID: 32868471; PMCID: PMC7461208.

- Trexler ET, Smith-Ryan AE, Stout JR, Hoffman JR, Wilborn CD, Sale C, Kreider RB, Jäger R, Earnest CP, Bannock L, Campbell B. International society of sports nutrition position stand: Beta-Alanine. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 2015 Dec;12(1):1-4.

- Hobson RM, Saunders B, Ball G, Harris RC, Sale C. Effects of β-alanine supplementation on exercise performance: a meta-analysis. Amino acids. 2012 Jul;43(1):25-37.

- Walsh AL, Gonzalez AM, Ratamess NA, Kang J, Hoffman JR. Improved time to exhaustion following ingestion of the energy drink Amino Impact. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2010;7:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-7-14.

- Spradley BD, Crowley KR, Tai CY, Kendall KL, Fukuda DH, Esposito EN, et al. Ingesting a pre-workout supplement containing caffeine, B-vitamins, amino acids, creatine, and beta-alanine before exercise delays fatigue while improving reaction time and muscular endurance. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2012;9:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-9-28.

- Gonzalez AM, Walsh AL, Ratamess NA, Kang J, Hoffman JR. Effect of a pre-workout energy supplement on acute multi-joint resistance exercise. J Sports Sci Med. 2011;10(2):261–6.

- Hoffman JR, Landau G, Stout JR, Dabora M, Moran DS, Sharvit N, et al. Beta-alanine supplementation improves tactical performance but not cognitive function in combat soldiers. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2014;11(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-11-15.

- Davis JM, Zhao Z, Stock HS, Mehl KA, Buggy J, Hand GA. Central nervous system effects of caffeine and adenosine on fatigue. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys. 2003;284(2):R399–404.

- Guest NS, VanDusseldorp TA, Nelson MT, et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and exercise performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2021;18(1):1. Published 2021 Jan 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-020-00383-4

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Spilling the Beans: How Much Caffeine is Too Much? Available at: https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/spilling-beans-how-much-caffeine-too-much. Published December 12, 2018. Accessed September 26, 2022

- Pasman W.J., van Baak M.A., Jeukendrup A.E., de Haan A. The effect of different dosages of caffeine on endurance performance time. Int. J. Sports Med. 1995;16:225–230. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-972996.

- Grgic J, Mikulic P, Schoenfeld BJ, Bishop DJ, Pedisic Z. The influence of caffeine supplementation on resistance exercise: a review. Sports Med. 2019;49(1):17–30.

- Pallares JG, Fernandez-Elias VE, Ortega JF, Munoz G, Munoz-Guerra J, Mora-Rodriguez R. Neuromuscular responses to incremental caffeine doses: performance and side effects. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(11):2184–92.

- Ramos-Campo DJ, Perez A, Avila-Gandia V, Perez-Pinero S, Rubio-Arias JA. Impact of caffeine intake on 800-m running performance and sleep quality in trained runners. Nutrients. 2019;11(9).

- Brunzel NA. Renal function: Nonprotein nitrogen compounds, function tests, and renal disease. In: Scardiglia J, Brown M, McCullough K, Davis K, editor. Clinical Chemistry. McGraw-Hill: New York, NY; 2003. pp. 373–399.

- Wax B, Kerksick CM, Jagim AR, Mayo JJ, Lyons BC, Kreider RB. Creatine for Exercise and Sports Performance, with Recovery Considerations for Healthy Populations. Nutrients. 2021;13(6):1915. Published 2021 Jun 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061915

- Williams MH, Kreider R, Branch JD. Creatine: The power supplement. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers; 1999. p. 252.

- Kreider RB, Leutholtz BC, Greenwood M. Creatine. In: Wolinsky I, Driskel J, editor. Nutritional Ergogenic Aids. CRC Press LLC: Boca Raton, FL; 2004. pp. 81–104.

- Hall M, Trojian TH. Creatine supplementation. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2013;12(4):240–244

- Davani-Davari D, Karimzadeh I, Ezzatzadegan-Jahromi S, Sagheb MM. Potential Adverse Effects of Creatine Supplement on the Kidney in Athletes and Bodybuilders. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2018;12(5):253-260.

- Vega J, Huidobro E JP. [Effects of creatine supplementation on renal function]. Revista Medica de Chile. 2019 May;147(5):628-633. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0034-98872019000500628. PMID: 31859895.

- Breen L, Philip A, Witard OC, et al. The influence of carbohydrate-protein co-ingestion following endurance exercise onmyofibrillar and mitochondrial protein synthesis. J Physiol.2011;589:4011–25.19.

- Howarth KR, Moreau NA, Phillips SM, et al. Coingestion of protein with carbohydrate during recovery from endurance exercise stimulates skeletal muscle protein synthesis in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1394–402.20.

- Moore DR, Stellingwerff T. Protein ingestion after endurance exercise: the ‘evolving’ needs of the mitochondria? J Physiol.2012;590:1785–6.21.

- Hulston CJ, Wolsk E, Grøndahl TS, et al. Protein intake does not increase vastus lateralis muscle protein synthesis during cycling. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1635–42.

- Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: Nutrition and Athletic Performance [published correction appears in J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017 Jan;117(1):146]. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(3):501-528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2015.12.006

- Jäger R, Kerksick CM, Campbell BI, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017;14:20. Published 2017 Jun 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-017-0177-8

- Bandara SB, Towle KM, Monnot AD. A human health risk assessment of heavy metal ingestion among consumers of protein powder supplements. Toxicol Rep. 2020;7:1255-1262. Published 2020 Aug 21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.08.001

- Mero A. Leucine supplementation and intensive training. Sports Med. 1999;27(6):347–358.

- Koo GH, Woo J, Kang S, Shin KO. Effects of supplementation with BCAA and L-glutamine on blood fatigue factors and cytokines in juvenile athletes submitted to maximal intensity rowing performance. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26:1241–1246.

- Da Luz C.R., Nicastro H., Zanchi N.E., Chaves D.F., Lancha A.H. Potential therapeutic effects of branched-chain amino acids supplementation on resistance exercise-based muscle damage in humans. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2011;8:23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-8-23.

- Greer B.K., Woodard J.L., White J.P., Arguello E.M., Haymes E.M. Branched-chain amino acid supplementation and indicators of muscle damage after endurance exercise. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2007;17:595–607. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.17.6.595.

- Blomstrand E. A role for branched-chain amino acids in reducing central fatigue. J. Nutr. 2006;136:544S–547S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.2.544S.

- Shimomura Y, Inaguma A, Watanabe S, et al. Branched-chain amino acid supplementation before squat exercise and delayed-onset muscle soreness. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2010;20(3):236-244. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.20.3.236

- Bloomgarden Z. Diabetes and branched-chain amino acids: What is the link? J Diabetes. 2018;10:350–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-0407.12645.

- Yoon MS. The emerging role of branched-chain amino acids in insulin resistance and metabolism. Nutrients. 2016;8:405. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8070405.

- Holeček M. Side effects of amino acid supplements. Physiol Res. 2022;71(1):29-45. https://doi.org/10.33549/physiolres.934790

- Pope HG Jr, Wood RI, Rogol A, Nyberg F, Bowers L, Bhasin S. Adverse health consequences of performance-enhancing drugs: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2014;35(3):341-375. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2013-1058

- Dandoy C, Gereige RS. Performance-enhancing drugs. Pediatr Rev. 2012 Jun;33(6):265-71; quiz 271-2. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.33-6-265. PMID: 22659257; PMCID: PMC4528343.

- de Hon, O., Kuipers, H. & van Bottenburg, M. Prevalence of Doping Use in Elite Sports: A Review of Numbers and Methods. Sports Med 45, 57–69 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0247-x

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Ephedra and ephedrine for weight loss and athletic performance enhancement: clinical efficacy and side effects. Available at: http://www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/epcsums/ephedsum.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2022

- Virtual Mentor. 2005;7(11):764-766. https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2005.7.11.oped1-0511.

- World Anti-Doping Agency. Who We Are. Available at: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/who-we-are. Accessed September 26, 2022

- World Anti-Doping Agency. The World Anti-Doping Code. Available at: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/what-we-do/world-anti-doping-code. Accessed September 26, 2022

- World Anti-Doping Agency. The Prohibited List. Available at: https://www.wada-ama.org/en/prohibited-list. Accessed September 26, 2022

- The National Collegiate Athletic Association. NCAA Banned Substances. Available at: https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2015/6/10/ncaa-banned-substances.aspx Updated July 14, 2022. Accessed September 26, 2022