In the context of personal training, special populations refers to any given subset of the general population that have special considerations when it comes to program design or exercise technique.

While many training principles apply across most populations, there are modifications and considerations that fitness professionals must make when working with various special populations.

An understanding of these modifications and when to apply them for certain types of clients greatly improves the fitness professional’s ability to successfully deliver fitness results and prevent injury.

Introduction to Special Populations

The main type of special populations clients fitness professionals must be familiar with are:

- Youth clients

- Older adult clients

- Pregnant clients

- Clients with chronic illnesses

There is always an additional risk factor in training special population clients. For clients with health conditions, medical clearance should always be obtained ahead of time.

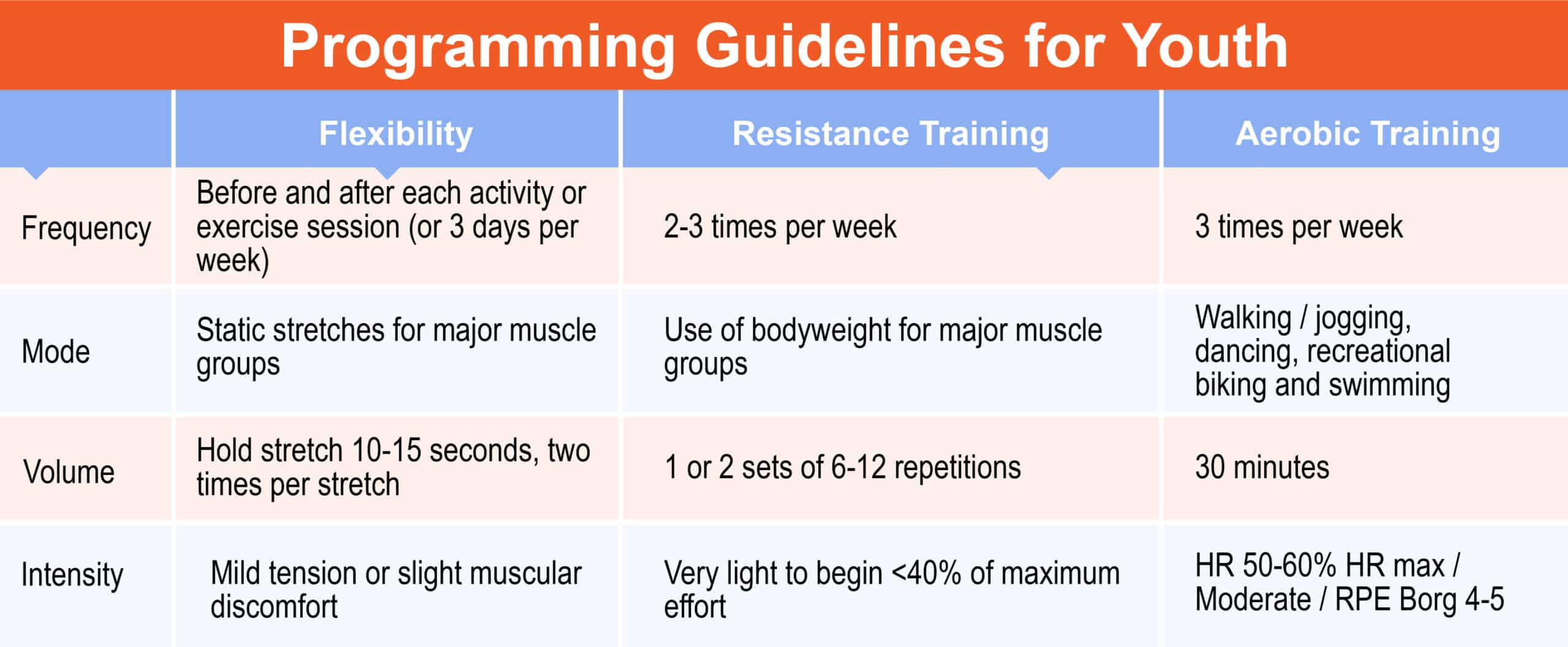

Programming Guidelines for Youth

Youth physical exercise typically comes from a combination of structured and unstructured activities. Considering youth are typically active in school periods or while playing sports, their ability to perform exercises over a longer period may be lower than that of a structured adult, due to overall fatigue.1

When developing a fitness program, individual programming should be considered for each child as abilities will be vastly different, regardless of similarities in age.

Incorporating age-appropriate sports helps to increase aerobic function. Exercising develops muscle and bone strength in youth populations.2, 3

Physiological Differences Between Children and Adults

Fitness professionals who train children must understand the physiological differences between various age ranges and their implications for safely exercising.

Children intake more oxygen per pound of body weight. They also have thinner skin, so dehydration and fluid loss is more prevalent.4

It is vital to ensure children stay well-hydrated, especially when exercising heavily or in a hotter environment.

Though children do respond well to exercise, their bodies adapt somewhat differently to exercise than adults.5, 6

Youth Flexibility

Flexibility is the ability to move joints through a full range of motion.8 Dynamic stretches help joints, and muscles move through their full range of motion. Assuming the child is otherwise healthy and mature enough to follow instructions, youth flexibility guidelines can follow adult flexibility guidelines.

Frequency

- Before and after each activity or exercise session (or 3 days per week)

Mode

- Static stretches for major muscle groups

Duration

- Hold stretch 10-15 seconds, two times per stretch

Intensity

- Mild tension or slight muscular discomfort

Special Considerations

- There are no special considerations unless the child has preexisting musculoskeletal conditions

Youth Resistance Training

Based on the latest research, youth resistance training for health and fitness conditioning shows a lower risk of injury when compared to playing traditional sports.8 The most common injuries associated with resistance training are strains and sprains, which are largely attributable to poor technique coaching or lack of adult supervision during the session.

Strength training in prepubescent youths improves muscular endurance and strength, improves motor skills, protects against injury, has positive psychological effects, and provides a platform for safe and proper training.9

Frequency

- 2-3 times per week

Mode

- Use of bodyweight for major muscle groups

Intensity

- Very light to begin <40% of maximum effort

Duration

- 1 or 2 sets of 6-12 repetitions

Special Considerations

- Main objective is to introduce resistance training and correct movement patterns before applying more weight

Movement Assessment

- Overhead squat, push, pull, single leg balance, single leg squat

Youth Aerobic Training

To create an appropriate aerobic training program for children, trainers must consider the maturity of the child, medical status, and their previous experience with exercise.

Regardless of age, the exercise intensity should start low and progress slowly. Children should be physically active every day to create positive habits, expend energy, and develop healthy physical habits.8 Provided proper technique guidelines are followed, children can safely perform most forms of aerobic exercise.

Frequency

- 3 times per week

Mode

- Walking/jogging, dancing, recreational biking and swimming

Intensity

Options:

- HR 50%-60% HRmax

- Moderate (beginning to sweat)

- RPE Borg 4- 5

Duration

- 30 minutes

Special Considerations

- Make activity fun, part of an active lifestyle

Training Guidelines for Senior & Older Adult Populations

Current estimates indicate there are over 35 million Americans aged 65 and above.10 Many older adults do not achieve the recommended amount of daily physical activity. Lack of exercise leads to lower metabolism, a weaker immune system, and chronic diseases.

Typical chronic diseases that develop are heart disease, stroke, diabetes, lung disease, Alzheimer’s, hypertension, and certain cancers.11, 12 A main component of aging is frailty with reduced physical function. Loss of muscular strength can lead to loss of independent living and an increased risk of developing various chronic diseases. Older adult populations are at a higher risk of developing osteoporosis, arthritis, low back pain, and obesity.12

Trainers must consider different risks that may require medical clearance and perform movement assessments to determine any muscle imbalances when designing exercise programs for seniors.

Some normal physiological adaptations that older adult populations experience are a decline in maximal attainable heart rate, cardiac output, muscle mass, balance, coordination, connective tissue elasticity, and bone mineral density.13

Aging fundamentally predisposes people to multiple morbidities that compound upon each other, often to the detriment of function and well-being.

For example, loss of skeletal muscle mass and bone mass accelerates in older populations which leads to less strength and a subsequent risk increase for falls and fractures.15

Hypertension is common in older populations because aging typically stiffens the arterial walls, due to the degeneration of elastic fibers and deposition of collagen and calcium in the walls of the arteries.16

This arterial stiffening raises the systolic blood pressure. Thus, isolated hypertension is commonly found in the elderly and constitutes a major risk factor. A healthy individual should have a blood pressure read of 120/80 mmHg and any individual, regardless of age, should be referred to their physician if their blood pressure reading is 140/90 mm Hg or higher.

Aside from the normal decline in physiological health, healthy older adults adapt to exercise the way normal, healthy adults would.13 Encouraging older adults to exercise and demonstrating proper technique will help build their confidence to participate in resistance training and mobility exercises.

Before initiating any physical training, older adults must complete a Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) and age-appropriate movement assessment to determine their capabilities before initiating an exercise prescription.

A flexibility assessment should be conducted with the movement assessment because older adults lose the elasticity of their connective tissue, which reduces range of motion and increases the risk of injury.

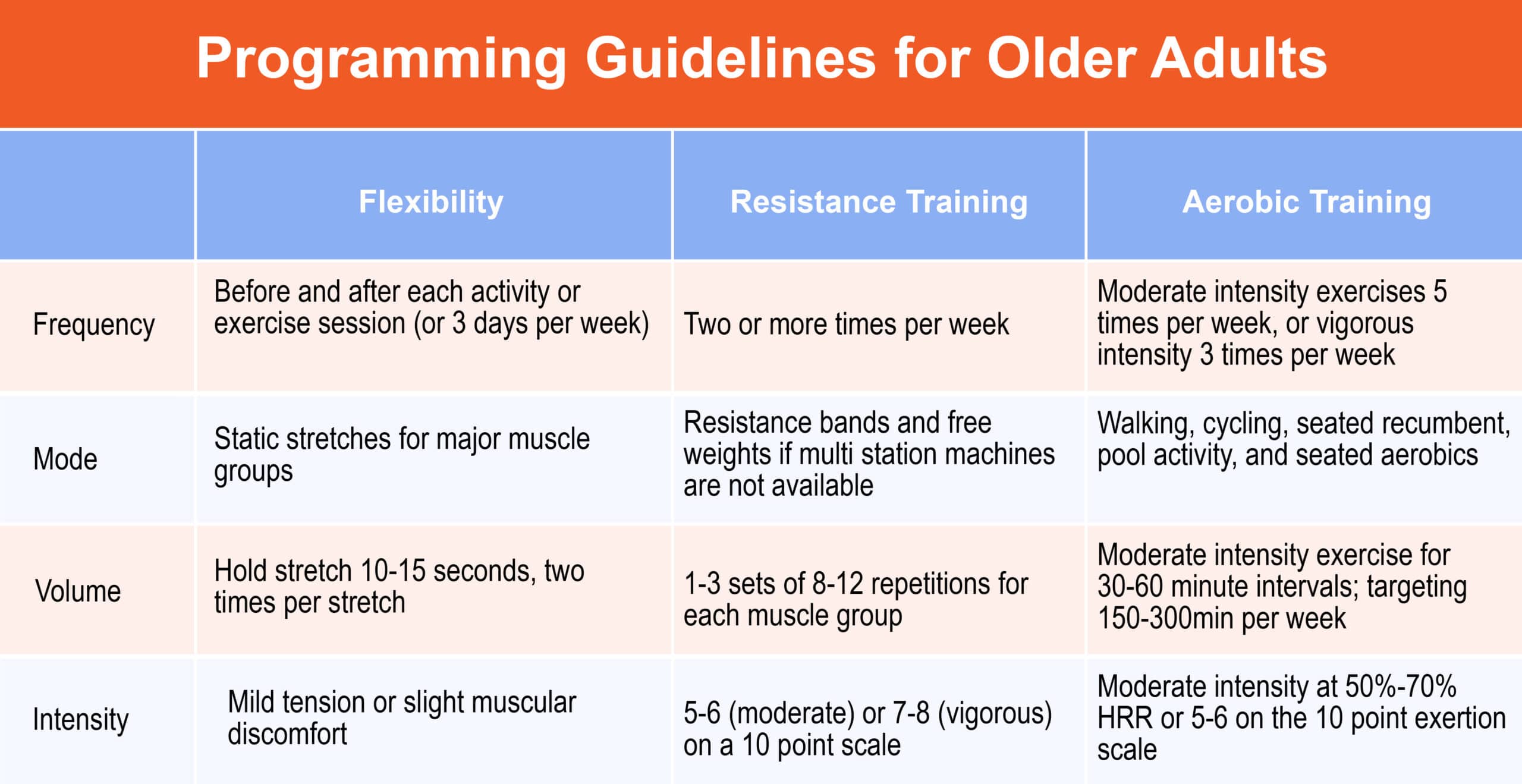

Older Adult Flexibility

Frequency

- Minimal two times per week

Mode

- Static Stretching

Duration

- 5-30 minutes total with 2 30-second bouts for each muscle group

Intensity

- Moderate intensity (5-6 on 0-10 scale)

Special Considerations

- Avoid ballistic movements and the Valsalva maneuver during the stretching routine

Older Adults Aerobic Training

Frequency

- Moderate intensity exercises 5 times per week, or vigorous intensity 3 times per week

Mode

- Walking, cycling, seated recumbent, pool activity, and seated aerobics

Duration

- Moderate intensity exercise for 30-60 minute intervals; targeting 150-300min per week

Intensity

- Moderate intensity at 50%-70% HRR or 5-6 on the 10 point exertion scale

Special Considerations

- Muscle strengthening exercises and/or balance training may need to precede aerobic training among frail older adults.

- Comorbidities such as arthritis, osteoporosis, and heart disease need to be considered.

- Highly deconditioned adults with limited functional abilities should start with a low intensity and duration of physical activity.

Older Adult Resistance Training

Frequency

- Two or more times per week

Mode

- Resistance bands and free weights if multi station machines are not available

Duration

- 8-12 repetitions for each muscle group

Intensity

- 5-6 (moderate) or 7-8 (vigorous) on a 10-point scale

Special Considerations

- Strength training regimens depend on maximum resistance as well as endurance; supervision and cueing is helpful.

- Proper breathing is important- avoid the Valsalva maneuver for safety.

- Focus on building major muscle groups before challenging balance.

Movement Assessment

- Push, pull, OVH Squat (if possible) or sit to stand in a chair for balance

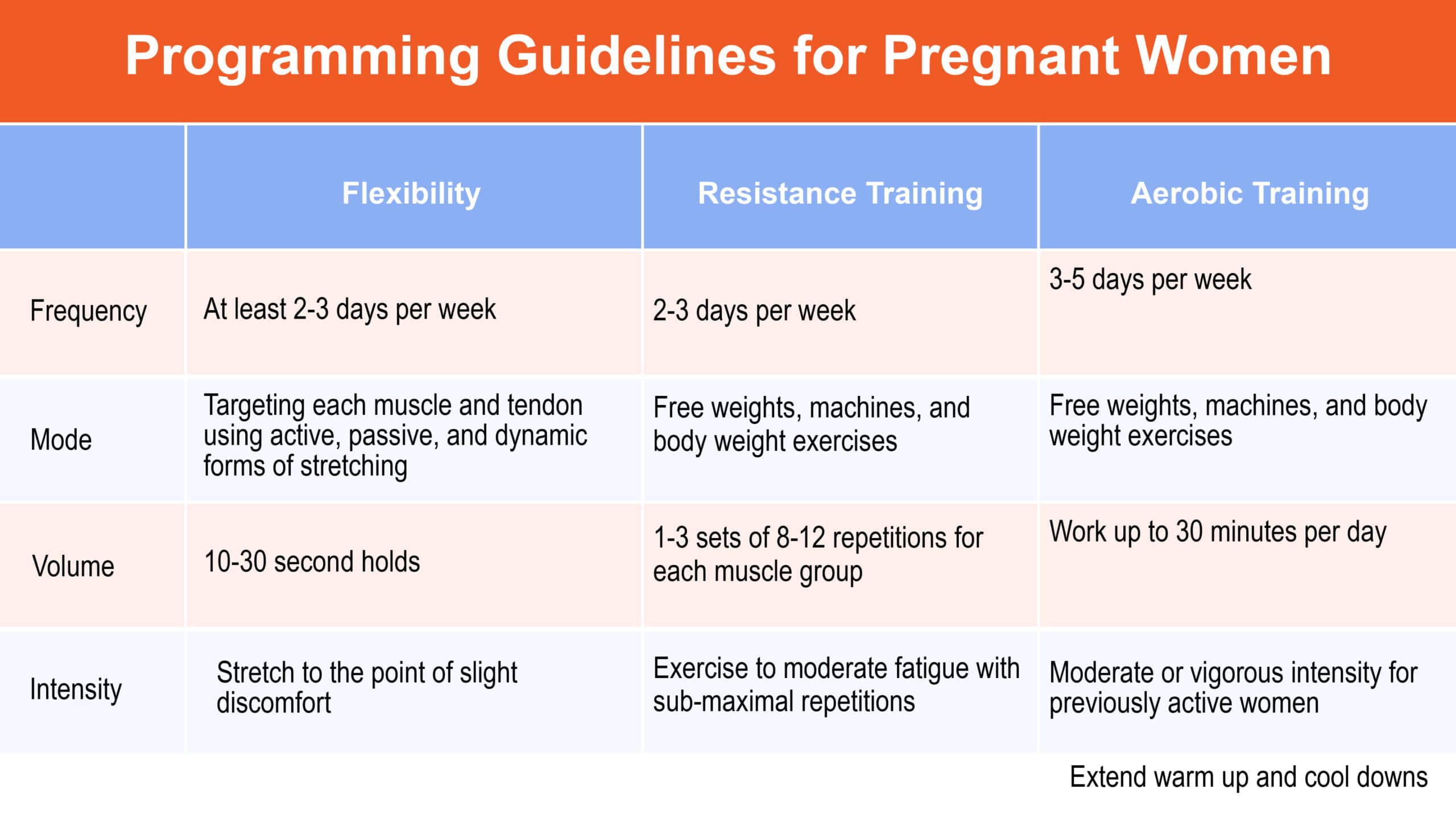

Training Considerations for Pregnancy

Collaborating with pregnant women to set appropriate and attainable goals will help them focus on efficacy, efficiency, and achieving success. Similar to a PAR-Q, having prenatal clients fill out a ParMed-X screening for pregnant women will help determine their level of readiness for an exercise program.17

Some exercises in the third trimester need to be contraindicated and avoided, like floor bridges and similar exercises.

Guidelines for Training Pregnant Clients

- If they already have an exercise prescription, continue this during the first trimester or minimum 30-40 minutes per day.

- With little or no previous exercise prescription, begin with 15 minutes of continuous exercise and slowly increase the duration to 30 minutes.

- During the second and third trimesters, vigorous exercise should be lowered.

- Avoid bouncing while stretching, exercises with risk of falling, sit ups, leg lowering exercises, and exercises performed in the prone position.

- Focus on hydration.

- Extend warm up and cool downs.

Contraindications to Training Pregnant Women

Some indications may be considered normal so please discuss first with the client. If new to exercise, pregnant women should be cleared for activity by their physician. These are a few contraindications to training pregnant women:

- Vaginal bleeding

- Dizziness

- Shortness of Breath

- Chest Pain

- Imbalance

- Swelling in outer limbs

- Painful contractions

- Amniotic fluid leakage

Aerobic Recommendations for Pregnant Women

Frequency

- 3-5 days per week

Mode

- Various weight bearing and non-weight bearing activities

Duration

- Work up to 30 minutes per day

Intensity

- Moderate or vigorous intensity for previously active women

Resistance Training During Pregnancy

Frequency

- 2-3 days per week

Mode

- Free weight machines and body weight exercises

Duration

- 1-3 sets for major muscle groups

Intensity

- Exercise to moderate fatigue with sub-maximal repetitions

Flexibility Training During Pregnancy

Frequency

- At least 2-3 days per week

Mode

- Targeting each muscle and tendon using active, passive, and dynamic forms of stretching

Duration

- 10-30 second holds

Intensity

- Stretch to the point of slight discomfort

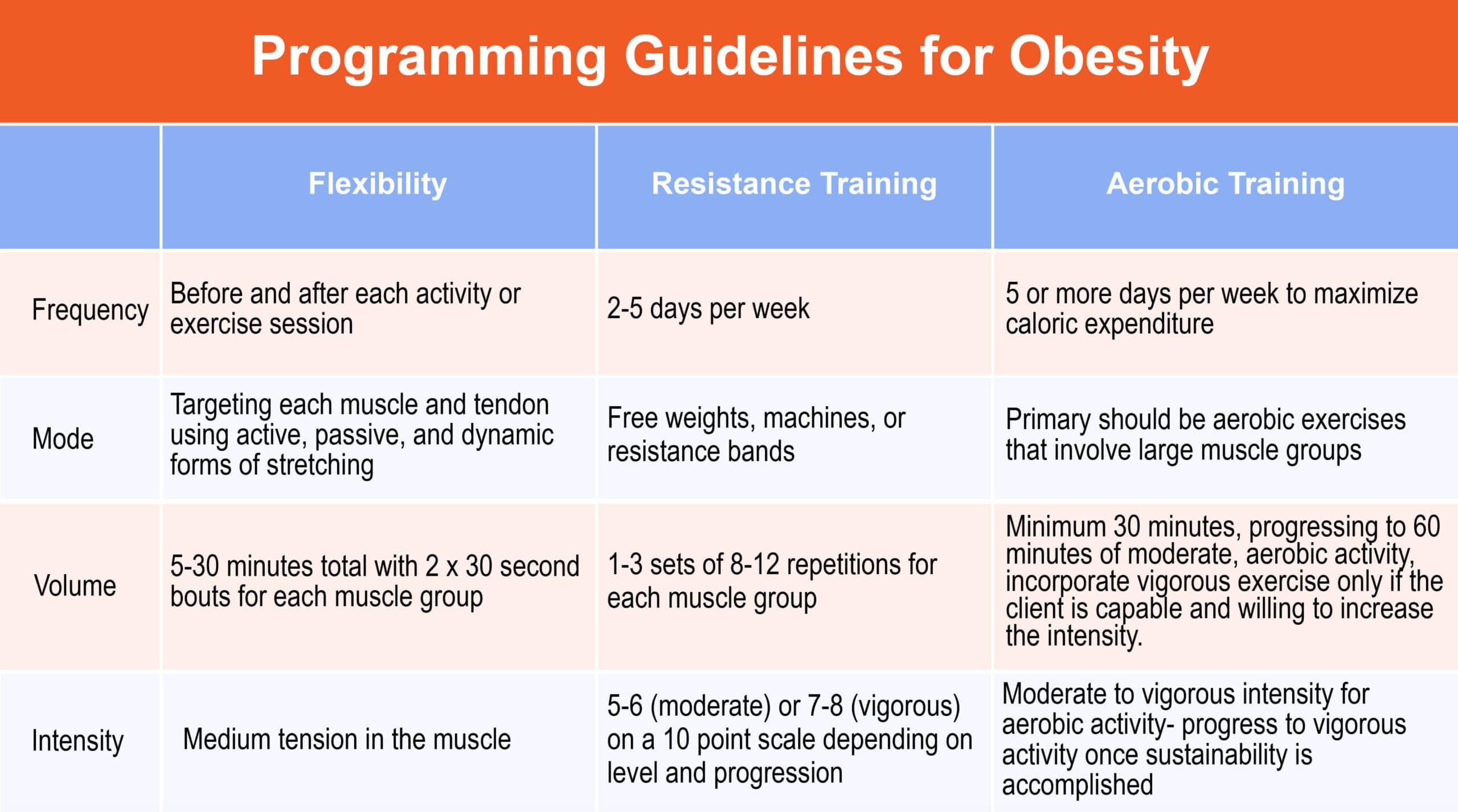

Training Considerations for Obesity

The World Health Organization defines overweight and obese as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health.19 Obesity is a rapidly growing issue in America where 1 out of 3 adults (68%) is overweight and over 31% of the population is obese.

The Task Force on Proposal for Public Actions states that obesity is largely a result of lifestyle. Short-term intervention has limited effectiveness, while long-term success is rare without an ongoing care plan or weight loss surgery.18, 19

Though weight loss surgeries can be successful in removing large amounts of fat, the person can gain it back if they do not commit to a fitness regimen and adequate nutrition planning.

In total, diet, lifestyle change, and exercise are essential components of obesity management.19

Body Mass Index

The common way to determine if a person is overweight or obese is to use body mass index (BMI). BMI is recommended by the National Institutes of Health to classify overweight and obesity and to estimate the relative risk of associated diseases.

Though this tool is widely used, it is important to note that BMI does not discriminate between fat mass and lean tissue. BMI does, however, significantly correlate with total body fat.20 Body mass index is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

There are other tools to measure accurate body fat such as skin fold calipers, but this can become an uncomfortable situation with overweight clients and often trainers who use calipers need to practice under someone more experienced before they are able to reliably take skinfold measurements.

A good tool to measure is the circumference of the client’s abdomen, arm, buttocks/hips, calf, forearm, hips/thigh, mid-thigh, and waist. Taking these measurements gives trainers a more accurate starting point for overweight and obese clients. For a start, measuring just the waist and hips can often be enough to get a rough idea of where a client is at.

Keeping in mind the inaccuracy of BMI, it is a helpful tool to develop achievable goals with overweight clients. A BMI of 18.5 to 24.9 is considered within a normal range, 25-29.9 is considered overweight, and a BMI of 30 or greater is obese.

As stated above, over 31% of Americans are obese, meaning their BMI falls into a range of 30 and above. This population-level increase in BMI leads to a corresponding increase in the various metabolic conditions associated with obesity.

Obesity and Exercise

Weight loss results derive from calories in versus calories burned and when excess calories are not expended, they are converted and stored as fat. While traditional advice would have trainers tell their clients to “eat less, run more,” there are additional environmental factors that contribute to overeating and decreased activity levels.

The availability of low-cost, calorie-dense, micronutrient-poor foods is a contributing factor along with a decrease in physical activity in both occupation and recreational activities.21 Personal trainers should work closely with dietitians to develop a balanced lifestyle that encompasses both a training program and a nutritional program.

Regardless of muscular strength, overweight and obese individuals tend to exhibit poor balance, slower gait velocity, and shorter steps.

Training should be focused on energy expenditure, balance, and proprioceptive training to burn more calories and improve posture, and gait.22

By programming proprioceptive exercises, there is greater potential for caloric expenditure, stability training, and greater muscle recruitment.23

For weight loss results, obese clients should expend 200 to 300 kcal per exercise session with a weekly average starting at 1200 kcal expended between physical activity and exercise.

Having clients start on an aerobic workout regimen is ideal for sustainability. Resistance training should be added into a training program starting at a lower intensity and employing modifications where necessary.

For obese clients who are hesitant to begin resistance training, taking increasingly longer walks is a good way to begin exercising.

However, incorporating some resistance training is important in a weight loss program because it helps increase lean body mass, which over time will improve metabolic function and overall body composition.24

Recommendations for Training Obese Clients

Frequency

- 5+ days per week to maximize caloric expenditure

Intensity

- Moderate to vigorous intensity for aerobic activity- progress to vigorous activity once sustainability is accomplished

Time

- Minimum 30 minutes, progressing to 60 minutes of moderate, aerobic activity

- Incorporate vigorous exercise only if the client is capable and willing to increase the intensity

Mode

- Primary should be aerobic exercises and weight lifting that involve large muscle groups

Assessment

- Push, pull, squat, single leg balance

Special Considerations

- Weight management relies on the relationship between energy intake and energy expenditure. However, a deeper look into the environmental effects on weight loss are important to note because sustainable weight loss will only be achieved if relative factors are addressed.

- To achieve weight loss, clients should aim to decrease current energy intake by 300-500 kcal, and progress to a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate intensity aerobic activity to optimize health. Increase exercise gradually for sustained weight loss.

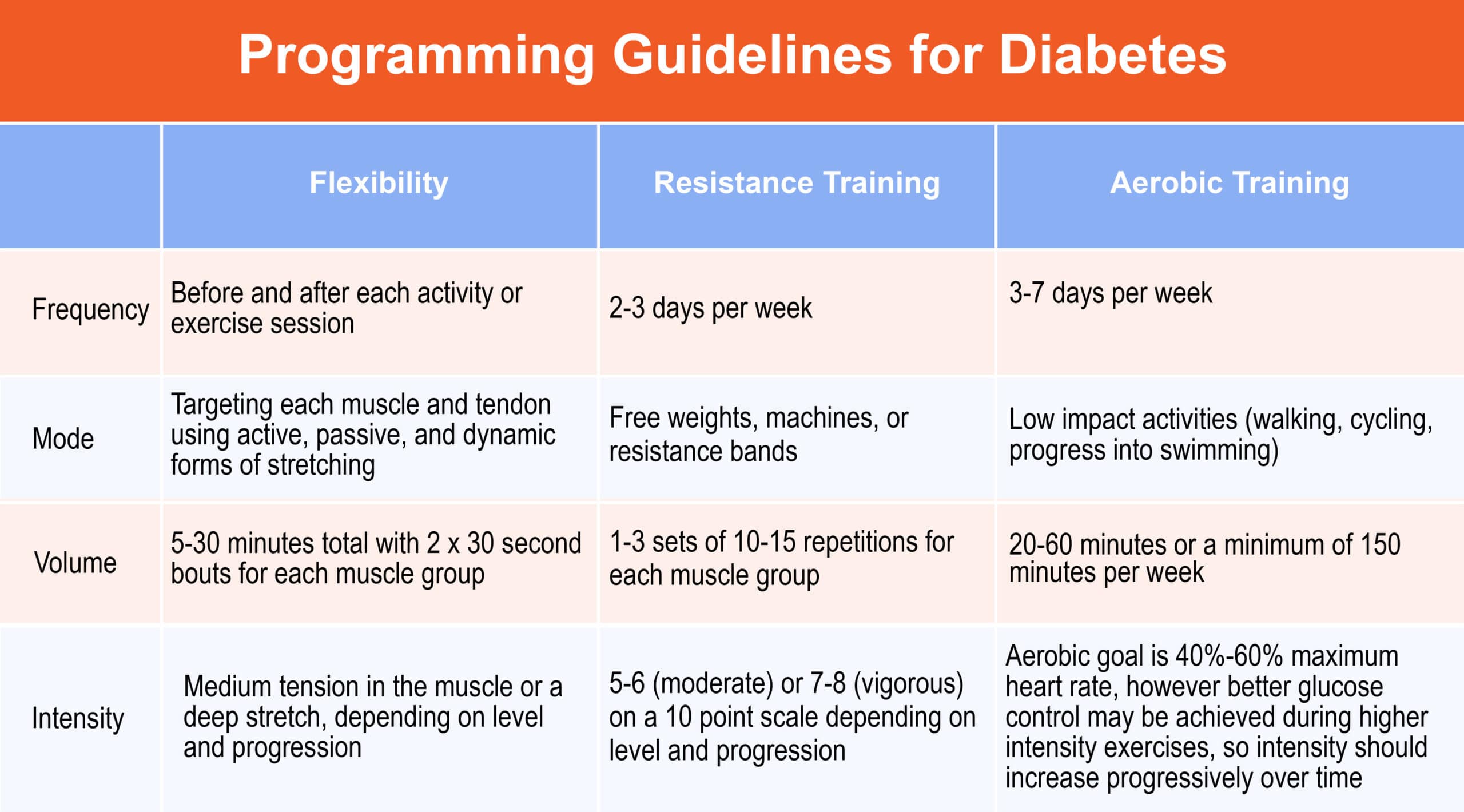

Training Considerations for Diabetes

Diabetes is the seventh leading cause of death in America.25 Diabetes is a metabolic disorder that affects how the body converts food into energy. The human body breaks down most food into sugar (glucose) and releases it into our bloodstream.

When there is an excessive amount of sugar, it signals the pancreas to release insulin and insulin allows blood sugar into cells to be used as energy. A person with diabetes does not produce enough insulin (type 1) or the body does not respond to the insulin that is being produced (type 2).

A primary characteristic of type 1 diabetes is insulin dependency while type 2 diabetes is caused by insulin-resistant skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and liver, combined with an insulin secretion deficit. A common cause of type 2 diabetes is excessive body fat with fat distributed in the upper half of the body.

However, some individuals may not be able to control their glucose levels, thus becoming insulin-dependent.26 To control the high levels of blood sugar, type 1 diabetics inject insulin to produce what the pancreas cannot.

Exercise increases the rate at which people utilize glucose, meaning insulin levels may need to be adjusted when performing the exercise.

It is important to control insulin levels before, during, and after exercise, because when blood sugar becomes too low, it creates a condition called hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) which can make the individual feel light-headed, dizzy, and short of breath.

Type 2 diabetes develops gradually and years can pass before severe symptoms arise. This is often called adult-onset diabetes and accounts for 90-95% of those with diabetes.27 With insulin resistance, the body cannot effectively use the insulin in the muscles or liver even though it produces a sufficient amount.

Over time the pancreas cannot secrete the insulin effectively to compensate for insulin resistance and hyperglycemia (high blood sugar). Genetic factors are a cause of type 2 diabetes, however, most people with this type are overweight or obese at the onset of symptoms.

Exercising with Diabetes

The fundamental goal for management of diabetes mellitus is glycemic control using diet, exercise, and, in many cases, medications such as insulin or oral hypoglycemic tablets.

More specifically, when focusing on individuals with type 2 diabetes, the main goal would be weight loss. By exercising the skeletal muscle, the body circulates glucose, creating a similar effect to insulin, thereby reducing insulin requirements.

Special Considerations

Hypoglycemia during exercise is the most common and serious problem in individuals with diabetes, especially for individuals who are taking oral medications or supplemental insulin. Rapid drops in blood sugar may occur in exercise, even when blood sugars are at a normal level. Common symptoms associated with diabetes include weakness, dizziness, shakiness, excessive sweating, anxiety, tingling, and hunger.6 Tracking an individual’s glucose levels throughout the program is necessary to maintain consistent levels.

Exercise should be scheduled knowing the client’s insulin timing to prevent hypoglycemic episodes along with adjusting carbohydrate intake before and after the workout to avoid hypoglycemic episodes.24 Recommend individuals with diabetes to exercise with a snack to avoid lowering their blood sugar.

Exercise Recommendations for Individuals with Diabetes

Frequency

- 3-7 days per week

Intensity

- Aerobic goal is 40%-60% maximum heart rate, however better glucose control may be achieved during higher intensity exercises, so intensity should increase progressively over time.

Duration

- 20-60 minutes or a minimum of 150 minutes per week

Mode

- Low impact activities (walking, cycling, progress into swimming)

Resistance Training

- 1-3 sets of 10-15 repetitions, 2-3 days per week

Assessment

- Push, pull, OVH Squat, single-leg balance, and single-leg squat

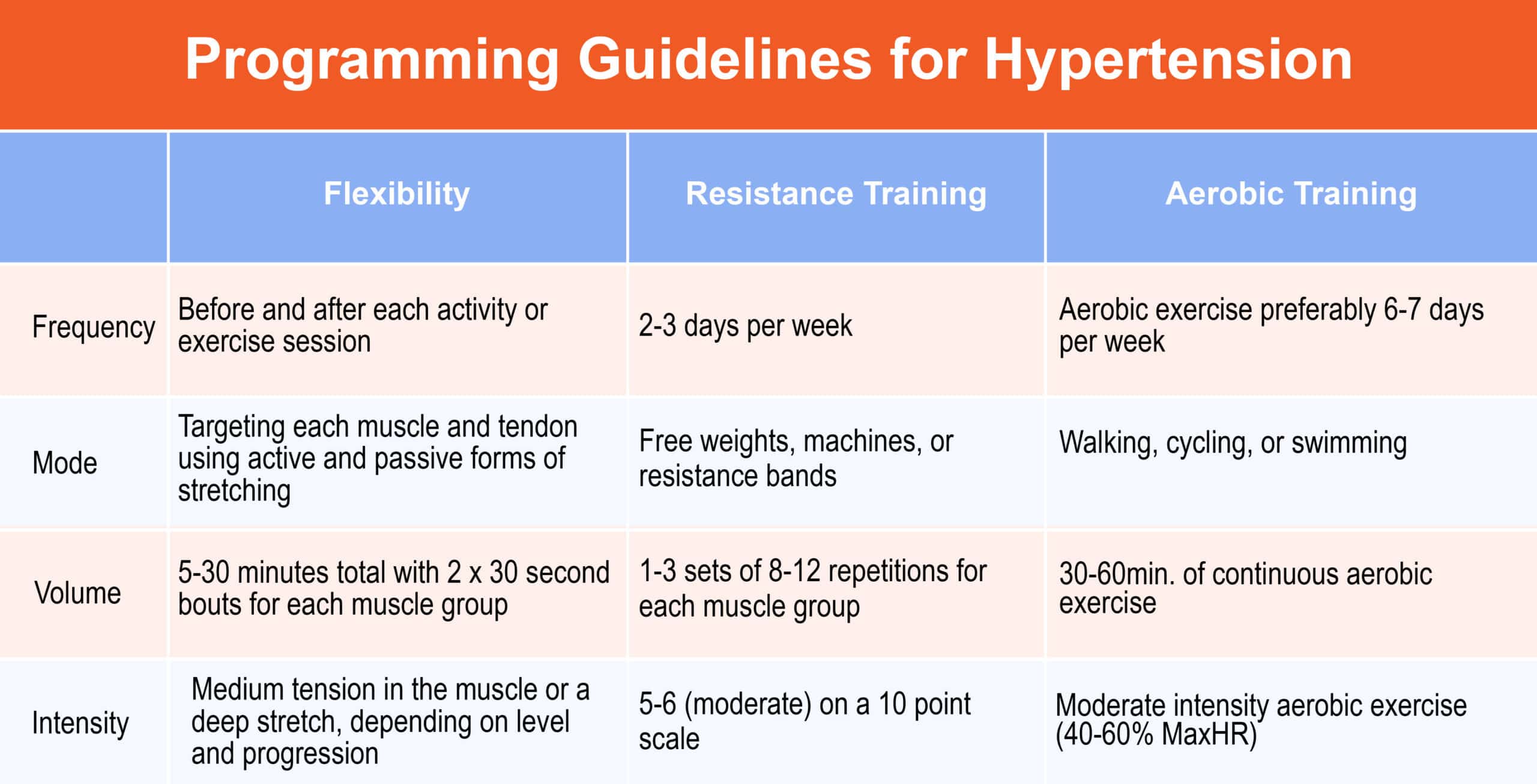

Training Considerations for Hypertension

Hypertension, commonly referred to as high blood pressure, is among the most common modifiable cardiovascular disease risk factors. Blood pressure is the pressure measured within large blood vessels, especially the arteries.

This pressure fluctuates depending on the strength of the heartbeat, the elasticity of the arterial walls, the volume and viscosity of the blood, as well as the person’s age, physical condition, and health. Blood pressure has two categories: systolic and diastolic.

The systolic (top number) measures the maximum pressure the heart exerts while beating, while the diastolic (bottom number) measures the pressure in the arteries between beats. A normal resting blood pressure used to read 120/80mmHg, however new guidelines by the American Heart Association suggest a healthy BP is “less than 120/80 mmHg.” Individuals classified with hypertension have a resting BP of 140 mmHg or greater or a resting diastolic BP of 90 mmHg or greater.

Personal trainers should know whether their clients are taking hypertensive medication before starting any exercise program. Hypertension increases cardiovascular risk factors such as disease, stroke, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, and chronic kidney disease. Medications are proven highly effective. However, lifestyle changes such as increased physical activity, diet, and quitting smoking have also been proven to decrease hypertension.

Aerobic exercise training leads to reductions in resting BP by nearly 5-7 mm Hg in individuals with hypertension.27 If personal trainers are able, they should measure their client’s blood pressure and heart rate before and again after the workout. These results should be logged during each session. Personal trainers should focus on aerobic activities for clients with hypertension, supplemented with moderate intensity resistance training.

Body position is extremely important when measuring heart rate or blood pressure. The client should not talk during measurements. They should sit upright in a chair with both feet flat on the ground for accurate results. Training regimens should be performed in a circuit-style to distribute blood flow between the upper and lower extremities. Clients should focus on deep breaths during exercise and avoid the Valsalva maneuver.

Exercise Recommendations for Individuals with Hypertension

Frequency

- Aerobic exercise on most, preferably 6-7 days per week, resistance training 2-3 days per week

Intensity

- Moderate intensity aerobic exercise (40-60% MaxHR) supplemented with resistance training at 60-80% 1-RM.

Duration

- 30-60 minutes of continuous aerobic exercise

Mode

- Emphasis should be placed on aerobic activities such as walking, cycling, or swimming. Resistance training should utilize free weights, machines, or resistance bands.

Movement Assessment

- Push, pull, OVH Squat, Single leg balance

Flexibility

- Static and active stretches in a standing or seated position

Special Considerations

- Avoid heavy lifting and the Valsalva maneuver.

- Do not perform the cardiovascular exercise if resting systolic BP exceeds 200 mmHg or diastolic BP exceeds 110 mmHg.

Training Considerations for Coronary Heart Disease

Approximately every forty seconds, a person has a coronary infarction (heart attack) in the United States.28 Fifty percent of all cardiovascular deaths are a result of coronary heart disease (CHD) making it the leading cause of death in both men and women.

CHD is caused by plaque formation or atherosclerosis. Plaque builds in the carotid, iliac, femoral, and aortic arteries, causing the narrowing of the blood vessels, which leads to poor perfusion and ultimately, heart failure.

The rate of progression of atherosclerosis may not be consistent, but there are several causes of plaque build up such as tobacco usage, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and various infectious agents.6, 29, 30

The goal of the fitness trainer in helping clients with CHD is to stabilize the buildup of plaque through a lifestyle change incorporating exercise, good nutrition, and adequate sleep.

Though moderate exercises are recommended for these patients, research indicates high-intensity interval training has significant increases on VO2 max, improvements in endothelial function, and lower resting blood pressure.31

Before beginning a training program, clients should be cleared by their physician for exercise. If the client has had an episode or myocardial infarction, they may have already completed a cardiac rehabilitation program. Trainers must stay up to date on medications their clients are taking and learn the signs and symptoms of a heart attack.

It is important for trainers to speak with clients about the benefits of participating in an exercise and nutrition program to improve their condition. A proper lifestyle change that incorporates exercise and nutrition can lower the risk of death, increase exercise tolerance, raise muscle strength, reduces CHD, and overall improves physiological health.

The risks of injury are low for individuals with CHD, however clients should be able to track their heart rate reliably and stay below their maximum allowed exertion as determined by their physican

Signs of CHD vary between individuals. However, if a client experiences chest pain, exercise should be stopped and the client should be assessed.

Individuals with CHD may also have comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, so trainers must comprehensively screen clients to develop proper modifications.

Exercise Recommendations for Individuals with Coronary Heart Disease

Frequency

- 3-5 days per week

Intensity

- Moderate: 40-85% Maximum HR

Duration

- 30 minutes per day of moderate intensity 5 days per week or 20 minutes of vigorous intensity 3 days per week

Mode

- Circuit training for large muscle groups, walking, cycling, group glasses

Movement Assessment

- Push, Pull, OH Squat, Balance

Flexibility

- Static or active stretching

Special Considerations

- Be aware that individuals with CHD may also have comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and/or obesity.

- Regress exercises if needed, such as training using a chair if necessary.

- Encourage regular, adequate breathing— avoid the Valsalva maneuver.

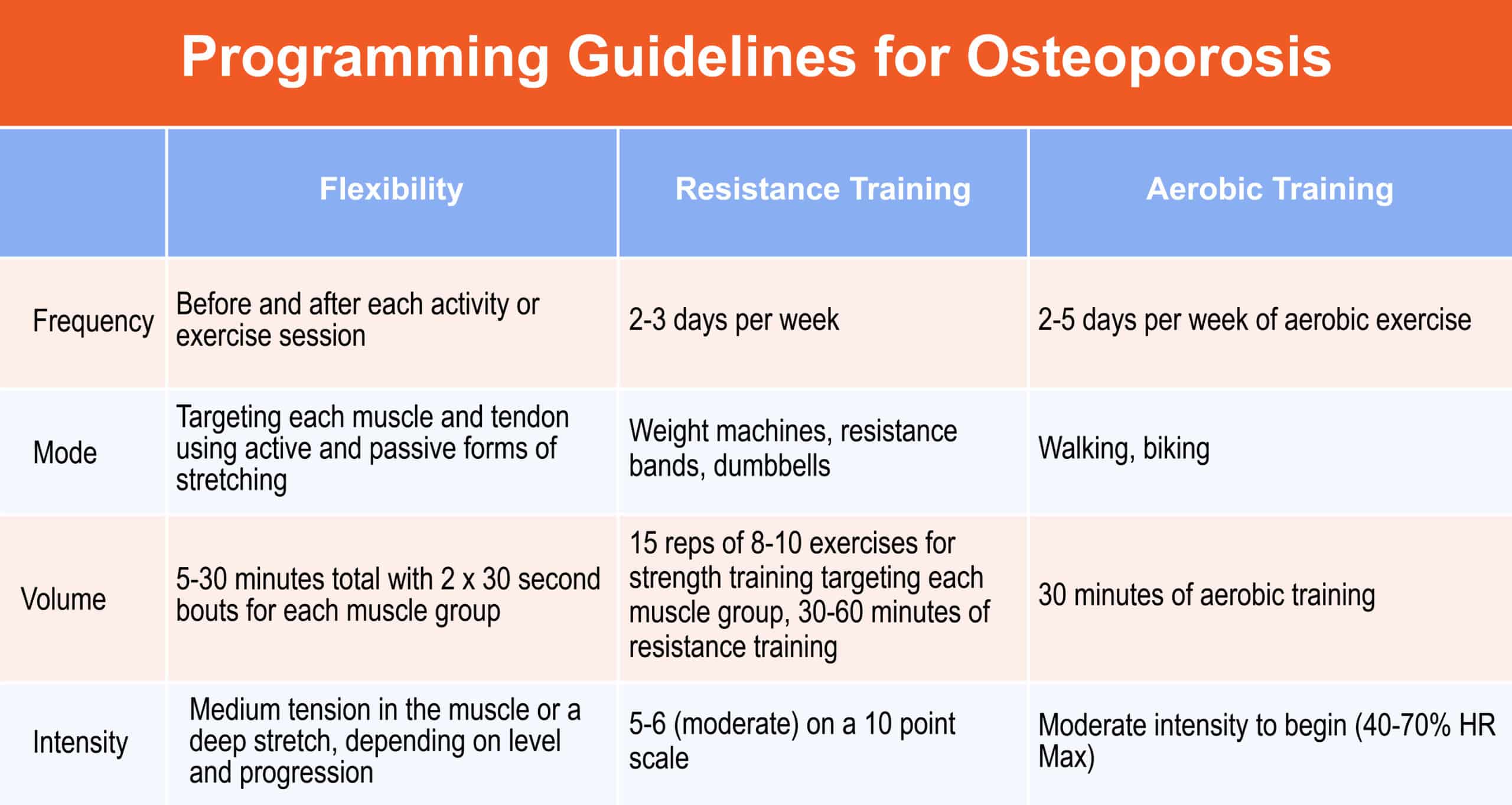

Training Considerations for Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterized by low bone density and deterioration of bony tissue,32 whereas osteopenia also indicates bone density loss, just at a lower level. In order to understand osteoporosis, it is first necessary to learn the physiology of bone formation, also known as bone remodeling. Over a person’s lifespan, bone remodeling maintains the architecture and structure of bones, regulates calcium level, and prevents fatigue damage.34

Bone mineral density increases during adolescence and begins to decrease after the age of forty. Bone loss occurs at a greater rate in women than men because women start with naturally lower bone density and their rate of bone loss increases 3-5 years after menopause. As such, women develop osteoporosis more often than men. Osteoporosis affects almost 50 percent women at some point in their life.33

A loss in bone density directly correlates to bone fractures and leads to increased morbidity and mortality.6 There are two main types of osteoporosis. Type 1 osteoporosis is developed as a result of natural aging, including lower productions of estrogen and progesterone, both of which are key components of regulating bone loss.

While type 1 is primarily due to the normal course of aging, type 2 encompasses other medical risk factors, medications, and lifestyle factors such as tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption. Both forms of osteoporosis are treatable.

The development of osteoporosis and osteopenia is asymptomatic, which leaves the disease undetected. Bone mineral density assessments are not always accurate. Often, a fracture is the first time the disease is detected. Before training a client with osteoporosis, it is imperative to obtain a history of their fractures and current bone mineral density.

Knowing this information will help develop a proper exercise program and minimize mechanical stress on the hip, spine, or wrist, which are at the highest risk. Other risk factors associated with osteoporosis development include physical inactivity and low calcium intake.

Fitness professionals must be aware of the contraindications for clients with osteoporosis. It is important to note that the areas most often affected by osteoporosis are going to be the femur and the lumbar vertebrae. The impact associated with traditional exercise movements may be excessive. As such, spinal flexion, high impact skeletal loading such as jumping, and stepping should be avoided along with twisting movements of the neck and spine.24

Gait and balance will have an effect on individuals with osteoporosis due to spinal fractures and joint impingements from bone deterioration, therefore client programs should include low intensity exercises.

Increasing physical activity improves bone mineral density and strength. Additionally, training adaptations typically improve balance, which reduces the risk of falling.

When training a client with osteoporosis, it is important for coaches to learn their client’s abilities and limitations. Though resistance training has been shown to improve bone density, they must assess to see if a specific exercise would improve their clients’ conditions or lead to a fracture. This is also the case when conducting movement assessments.

If a client is capable of standing, then performing exercises such as push, pull, and overhead squat movements are appropriate. Otherwise using exercise equipment to assist with the movement assessment will be helpful.

An exercise program for clients with osteoporosis should create variable weight distributions on the bones and focus on strengthening the main joints that become overloaded like the hips, spine, wrists, and lower back.35 An exercise program should not be substantially different than that of a normal individual of the same age.

Exercise Recommendations for Individuals with Osteoporosis

Frequency

- 2-5 days per week of aerobic exercise and 2 days per week of strength training

Intensity

- Moderate intensity to begin (40-70% HR Max) or 15 reps of 8-10 exercises for strength training

Duration

- 30 minutes of aerobic training or 30-60 minutes of resistance training

Mode

- Walking, biking, weight machines, resistance bands, dumbbells

Special Considerations

- Avoid jogging and other exercises that increase the risk of falling.

- Avoid spinal flexion and rotation.

- Encourage slow and controlled movements to maintain proper form.

- Focus exercises on strengthening target joints: hips, lower back, wrists, and spine.

- Osteoporosis is not a contraindication to exercise. In fact, exercising helps increase bone mineral density and improve quality of life. It is important to build confidence in a client’s balance so they feel safe performing everyday duties.

- A health report should be obtained from the individual so the trainer can develop an exercise program appropriate to their abilities.

- Flexibility should be limited to static and active stretching, using a chair if necessary.

- Develop exercise programs with longevity and progression in mind as it takes time to improve bone mineral density.

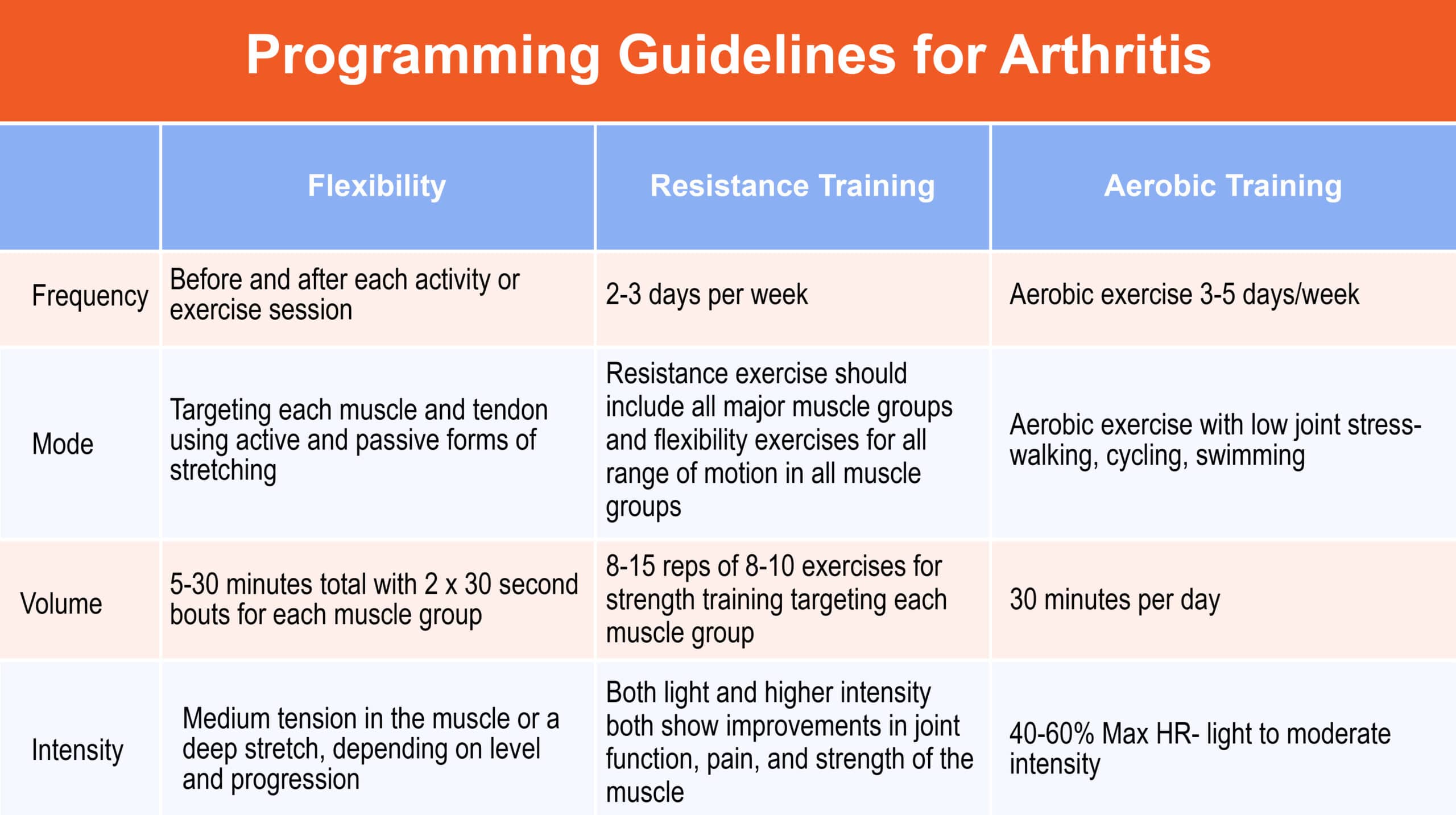

Training Considerations for Arthritis

Arthritis is an acute or chronic inflammation in one or more of the joints. There are a wide variety of symptoms associated with arthritis such as joint stiffness, pain, decreased range of motion, and joint deformities.36

There are over 100 different forms of arthritis, all varying in degrees of joint mobility, deterioration of the muscle tissue, and pain.

The two most common types personal trainers will encounter with clients are osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In both conditions, exercise has a major impact on those living with the disease. Exercise helps to support the affected joint by building strong supportive muscles around the joint.

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis involves degeneration of the cartilage within joints, which develops gradually and particularly affects the articulating bones.

Constant movement with diminishing cartilage causes bone-on-bone rubbing, inflammation around the joint, and weakening of ligaments and tendons. Symptoms of OA include stiffness, deformities, crepitus, and bone spurs.

The most affected areas include large weight-bearing joints such as the hips and knees, the hands, feet, and the spine.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disorder that begins affecting the small joints first, then larger joints, and eventually the organs. This disease destroys the cartilage in joints, causes joint stiffness, inflames the ligaments and tendons, and is very painful for individuals.37

Movement assessments should analyze the joint function and should be reassessed throughout the client’s exercise program to monitor their arthritis and symptoms.

Pain will be a major barrier when beginning or maintaining a program, therefore the goal should be to avoid painful movements while also keeping the program relevant.

Exercise programs can interact at each stage of arthritis and can help mitigate the effects of the disease on the deterioration of physical development. It is recommended clients follow a program that develops strength and stability to improve balance and joint strength.

Trainers will likely encounter deconditioned individuals with this disease so it is ideal for them to start their training with flexibility in the seated position before progressing to standing. Throughout the workout, trainers should ask the client if they are experiencing flare-ups, heat, or pain and adjust the workout accordingly.

Exercise Recommendations for Individuals with Arthritis

Frequency

- Aerobic exercise 3-5 days/week, resistance exercise 2-3 days/week

Intensity

- 40-60% Max HR- light to moderate intensity- both light and higher intensity both show improvements in joint function, pain, and strength of the muscle

Duration

- 30 minutes per day

Mode

- Aerobic exercise with low joint stress- walking, cycling, swimming.

- Resistance exercise should include all major muscle groups and flexibility exercises for all range of motion in all muscle groups.

Special Considerations

- Avoid strenuous exercises during flare ups and when highly inflamed.

- Adequate warm up and cool downs help to wake up the joints and invite movement into the body.

- Avoid heavy lifting to protect the bone structure.

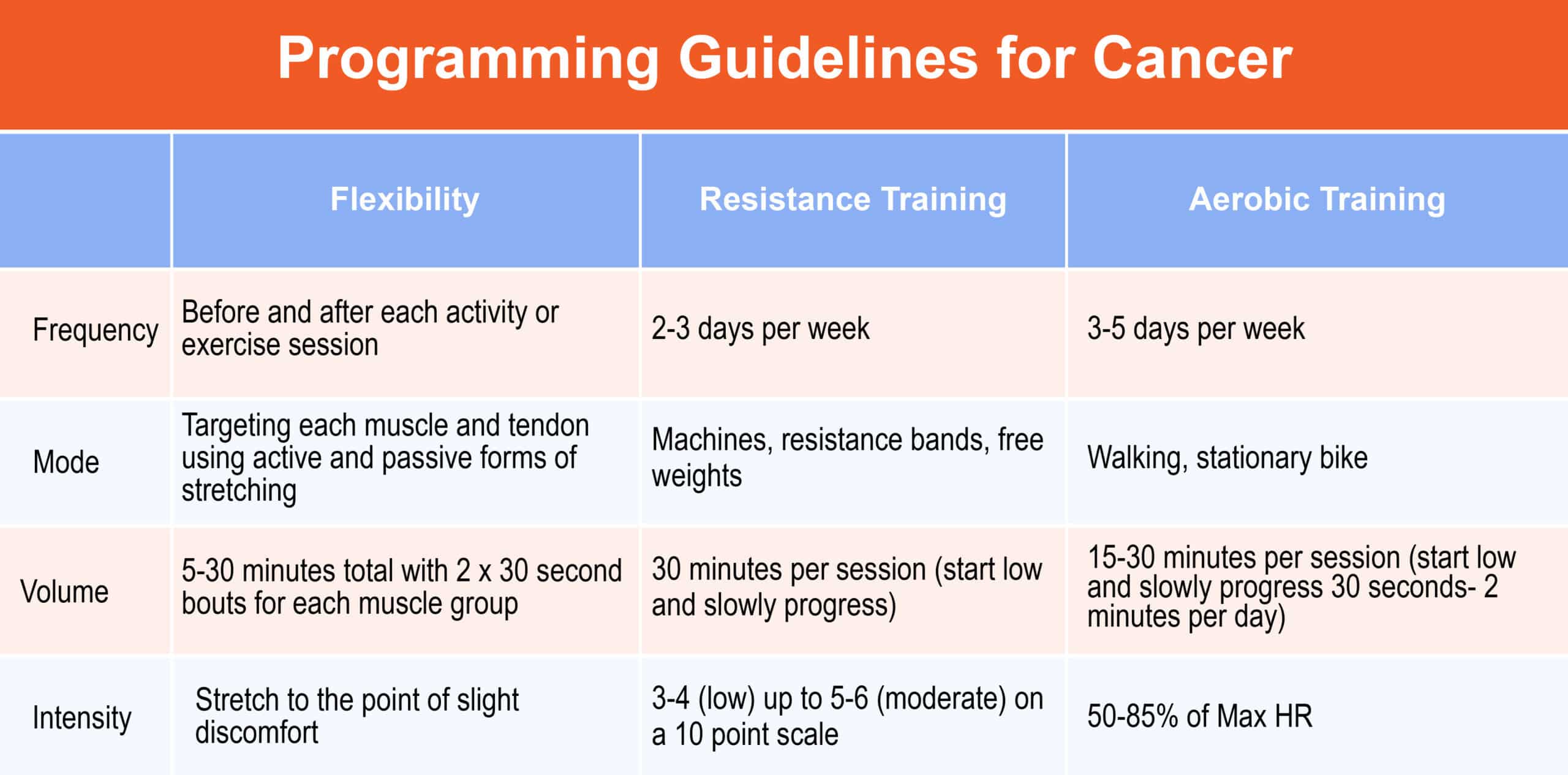

Training Considerations for Cancer

Cancer describes a range of diseases characterized by an uncontrollable growth of abnormal cells that divide and spread through other organ tissues. Cancer management modalities involve surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, hormones, and immunotherapy.39

Clients who are going through any of these treatments during training may experience side effects that may limit their ability to complete workouts due to a decrease in overall physical function, muscular strength, and joint range of motion.

In recent years, studies have shown that regular moderate intensity exercise enhances immune function, which lowers the susceptibility to cancer.

Long term effects of exercise promote anti-inflammatory effects because of the reduction in body fat and release of catecholamines.40

Personal trainers should have an overall understanding of how to develop an exercise regimen for this population and should judge their clients abilities in strength, balance, flexibility, and mobility.

Exercise at a moderate intensity for moderate durations has a positive effect on the immune system and research shows that moderate to high intensity activity is associated with a decrease in mortality in certain forms of cancer.

Individuals with cancer typically experience fatigue and weakness quicker than healthy individuals. Exercises should be primarily aerobic based at low- moderate intensity with many breaks. Exercise duration, frequency, and intensity should be progressed slowly as tolerated by the client.

The American College of Sports Medicine guidelines for cancer survivors does not state any differences in training individuals that are healthy post-cancer, so an exercise program for otherwise healthy cancer survivors should include flexibility, resistance, and aerobic training.24

Exercise Recommendations for Individuals with Cancer

Frequency

- 3-5 days per week

Intensity

- 50-85% of Max HR

Duration

- 15-30 minutes per session (start low and slowly progress 30 seconds- 2 minutes per day)

Mode

- Walking, stationary bike, free weights, resistance bands

Special Considerations

- Intensity may need to be adjusted during exercise. If needed, conduct a few exercises multiple times per day.

- Allow for adequate rest between sets.

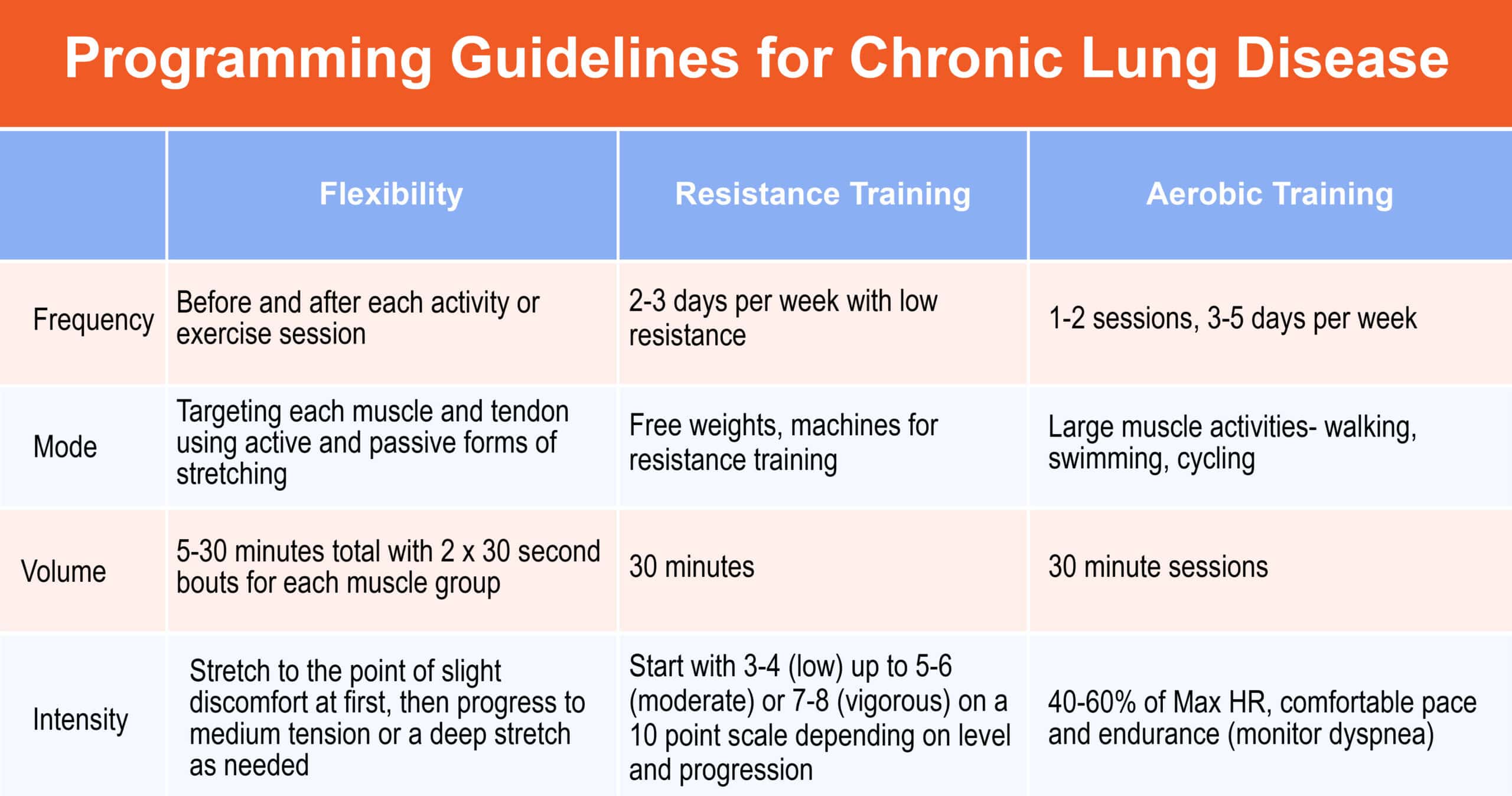

Training Considerations for Chronic Lung Disease

Chronic lung disease includes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), sleep-disordered breathing, and interstitial lung disease. Smoking is a primary risk factor for developing chronic lung disease and though cigarette smoking is on the decline, there is significant data that shows the negative effects of vaping and e-cigarettes on lung function.41

There are two major types of chronic lung disease: restrictive and obstructive. Restrictive lung disease is categorized by a reduced playability of the lung tissue; compromising lung expansion by reducing lung volumes, which decreases total lung capacity.

Obstructive lung diseases revolve around blockages in the air passageways that limit ventilation.

Major obstructive lung diseases include asthma, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema. Mucus builds in the lungs and air passages which leads to chronic inflammation that obstructs the airway. Chronic lung diseases are developed throughout life, so even though cystic fibrosis is a lung inflammatory disease, it is also a genetic disorder.

Exercise training has been shown to improve lung function and lung tissue in individuals with lung disease. Exercise increases functionality and though there is a decrease in ventilation and gas exchange for these individuals, it is possible to program to their tolerance.

Individuals with lung disease will experience shortness of breath which may then lead to dizziness so being mindful of intensity levels is key to developing an appropriate resistance and aerobic workout. Individuals with emphysema typically are underweight and experience shallow breathing because of a lack of neck and upper back muscles. On the contrary, individuals with chronic bronchitis are typically overweight with a large chest.6

Training methodologies for individuals with lung disease are similar to that of a healthy person. Clients exercising with lung diseases will fatigue sooner. Exercising lung function will strengthen the diaphragm that helps fill the lungs, and decrease symptoms of dyspnea, or shortness of breath.

Developing an exercise regimen utilizing resistance of the lower body is an excellent starting point since upper body exercises will require additional support of the muscles in the lungs.

Progress slowly and begin training at a low intensity and breath focus. Clients in this population are typically on medications or inhalers to open the bronchioles and alveoli of the lungs.42, 43 It is important to know what these medications are, trainers should have them bring their medications for each session, and learn how these medications will affect the training.

There are a few considerations when training individuals with chronic lung disease. Arm exercises require accessory muscles of inspiration so programming lower extremity exercises will help to develop lung function but will not fatigue the client preemptively.

A workout regimen aimed at improving lung function through resistance training could benefit those with obstructive lung disease through training 2-3 days per week at 30 minutes in duration with low resistance. Another consideration for those with lung disease is deconditioning of the muscles and lungs.

Depending on which type of lung disease they have, they may be overweight, underweight, or not active so exercise programming should revolve around the clients’ shortness of breath and tolerance.

If clients are using supplemental oxygen during a workout, trainers should not adjust their flow. This is considered a medication and if the client is experiencing shortness of breath, exercise should stop and their physician should be consulted.6

Exercise Guidelines for Individuals with Lung Disease

Frequency

- 1-2 sessions, 3-5 days per week

Intensity

- 40-60% of Max HR, comfortable pace and endurance (monitor dyspnea)

Duration

- 30 minute sessions

Mode

- Large muscle activities- walking, swimming, cycling and free weights, machines for resistance training

Special Considerations

- Exercise compliance should be considered in the determination of exercise intensity.

- Shorter intermittent sessions may be necessary initially.

- Respiratory muscle weakness is common.

- Upper body exercises contribute to dyspnea and inspirations muscle may require training.

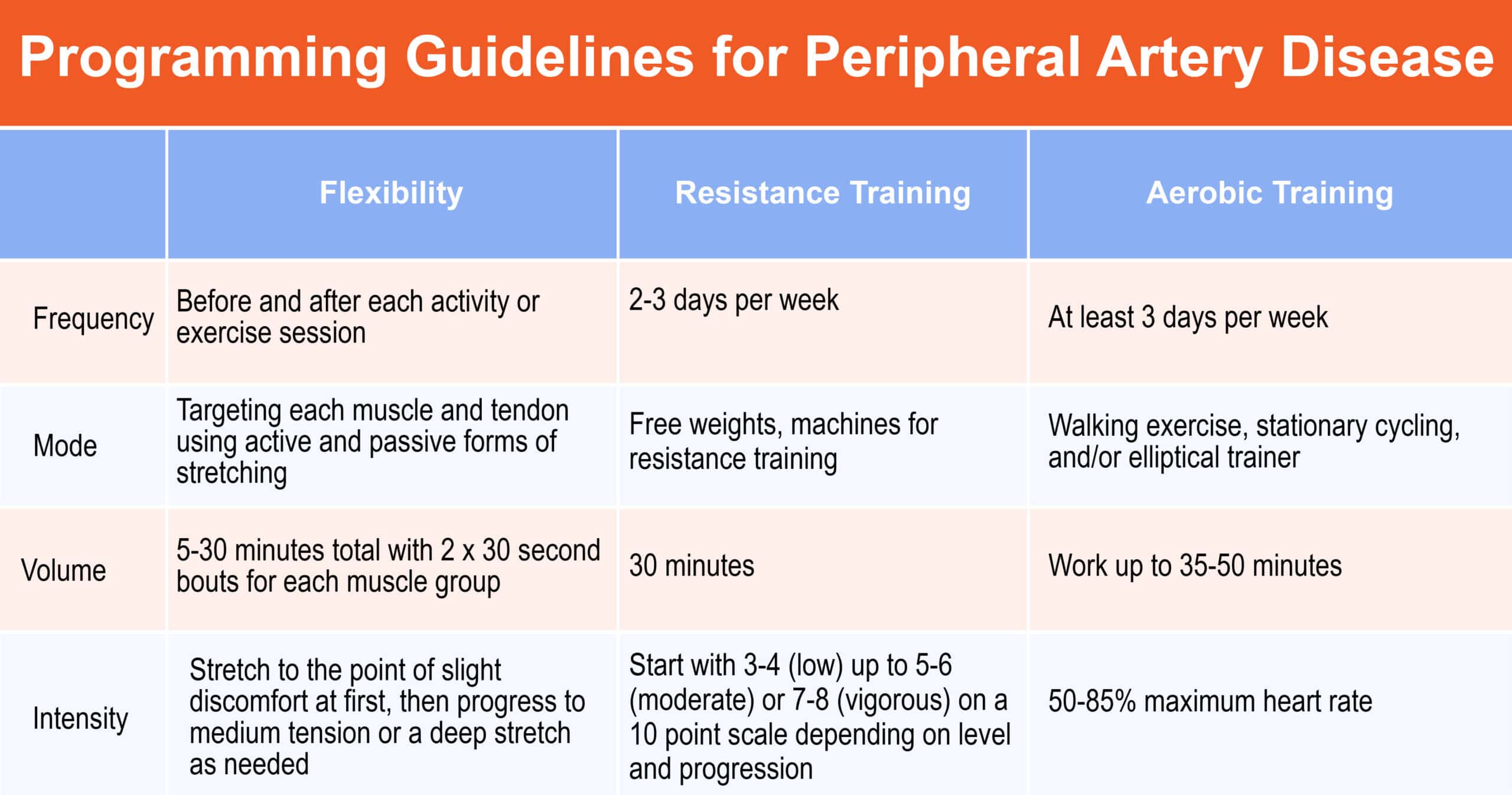

Training Considerations for Peripheral Artery Disease

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) occurs as the result of developing atherosclerotic plaque in the internal walls of the major arteries in the legs. This disease decreases functional capacity in oxygenated blood flow, increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases, and is associated with a higher risk of mortality.

Individuals can be asymptomatic or experience symptoms associated with PAD including intermittent claudication (IC) which encompasses pain, cramping, and aching in the calves, thighs, or buttocks. It may be difficult to distinguish deconditioning and PAD, so if clients complain about these symptoms, it is best to have them see their physician first.

Some traditional risk factors associated with PAD include advanced age, smoking, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.44 It is important to know that PAD often comes with other comorbidities and is associated with obesity, coronary heart disease, and diabetes so exercise can significantly help control and even lower the risk of these morbidities.

A properly developed training program should increase exercise performance by increasing oxygen consumption by 15-30%, increasing walking ability and quality of life. Regular exercise increases leg blood flow and reduces blood viscosity so it does not pool in the lower extremities.

There are several training considerations to follow for individuals with PAD. Beta-blockers decrease the time to claudication so understanding which medications clients are taking is important for programming. Cold weather exacerbates pain, so trainers should exercise clients in a warm environment, when possible.

When clients have a known coexisting coronary disease or diabetes, coaches will have to adjust the intensity and maximum heart rate. Resistance training promotes claudication so it should be in addition to aerobic exercising and always to the client’s pain tolerance.6, 45

Exercise Guidelines for Individuals with Peripheral Artery Disease

Frequency

- At least 3 days per week

Intensity

- 50-85% maximum heart rate

Duration

- Work up to 35-50 minutes

Mode

- Walking exercise, stationary cycling, and/or elliptical trainer

Special Considerations

- Begin exercise at 5-10 minutes and increase from there.

- For asymptomatic PAD, IC may not be a duration-limiting factor so the level of exertion should be used to guide exercises.

- Allow for sufficient rest between sets.

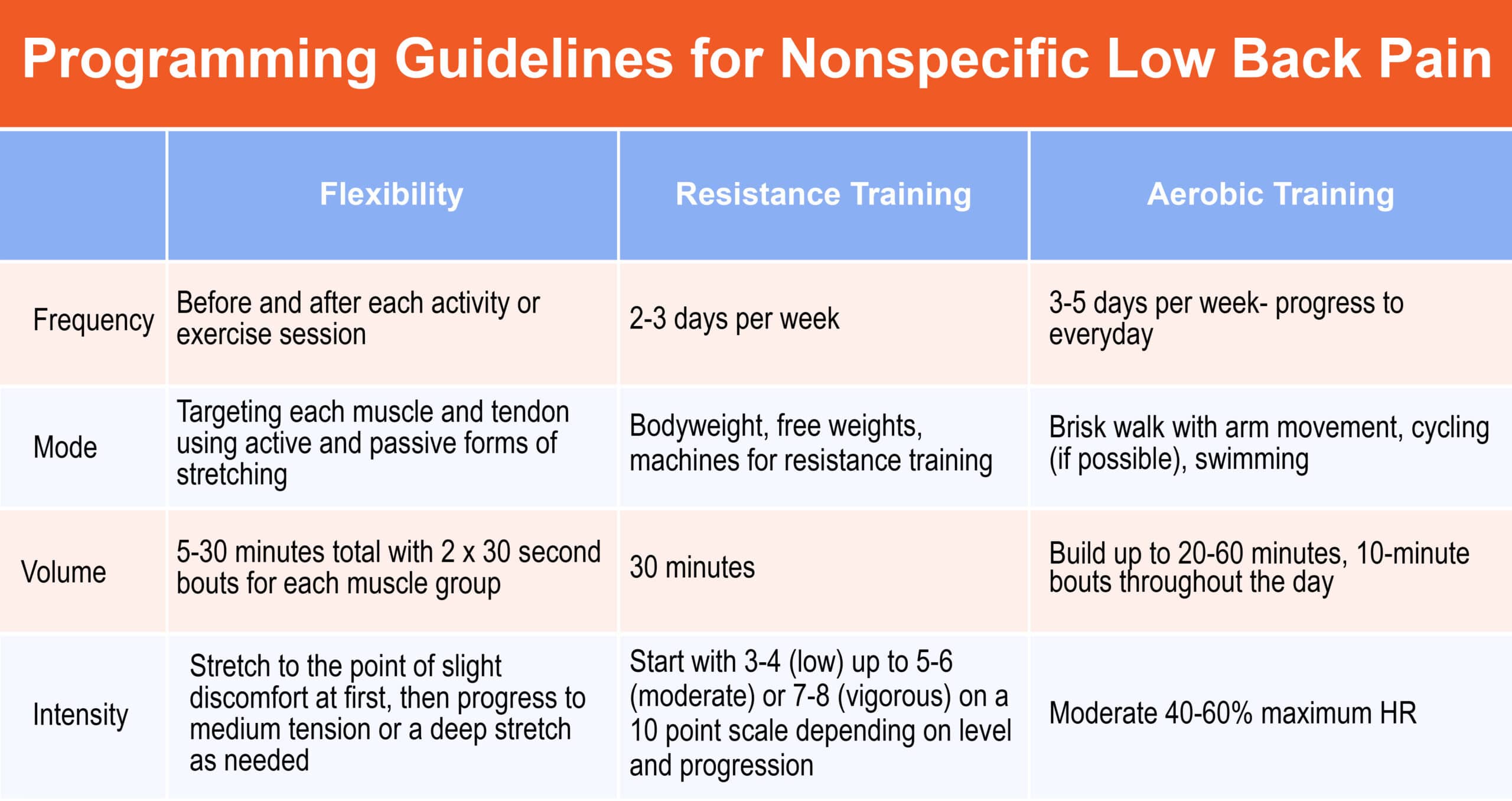

Training Considerations for Nonspecific Low Back Pain

Nonspecific low back pain (NSLBP) remains a condition that many people in society suffer from. It is the most musculoskeletal complaint in the world with 85% of people complaining about NSLBP in their lives. This condition does not only affect individuals physically, but also mentally and socially. When the symptoms of NSLBP affect ability to move, then someone’s ability to socialize decreases, and chances of depression significantly increase.

This topic is listed under special populations because each client trainers encounter with NSLBP may have different symptoms and should always be monitored for inflammation, additional pain, or new symptoms. NSLBP includes pain in the lumbosacral area that is not attributed to any known or recognizable disorders such as tumors, osteoporosis, inflammation, deformities, disc disease, or spinal compression.46

There are three subtypes of NSLBP that account for the duration of the pain:

- Current: less than 6 weeks

- Sub-acute: 6-12 weeks

- Chronic: 12 weeks or more

Treatment to find out the cause of back pain includes medical interventions and screenings such as x-rays or MRI.

There are many tendons, ligaments, and nerve roots flowing through the lower back that makes diagnosing difficult to narrow down. Disc deformities can be a factor in NSLBP and a medical screening should be obtained before beginning an exercise prescription.

A client with NSLBP may complain of generalized pain in the lumbosacral region. Pain will differ between individuals in intensity, duration, and frequency. Some may experience radiating pain with sensory changes, numbness, or lower extremity weakness.

Research states that individuals with NSLBP have decreased activation of certain intrinsic core muscle groups including the transverse abdominis, internal obliques, pelvic floor muscles, multifidi, diaphragm, and deep erector spinae.47

In addition to a decrease in core muscle activation, individuals with NSLBP tend to have decreased muscular endurance, and trunk muscle weakness. Promoting exercise to strengthen the lower back is strongly suggested to help alleviate the pain and avoid bed rest, however weight bearing activities can increase symptoms in certain planes of motion and postures.

Before executing exercises, it is vitally important to explain and demonstrate how to locally and globally stabilize the core, because, if not properly addressed, exercises can increase pressure on the discs and can cause damage to ligaments and supporting vertebrae.

A general rule is to strengthen the muscles of the core first before strengthening to outer extremities. Strengthening the muscles of the core should be progressive and have longevity in mind.48

Training considerations vary case by case however prevention should be considered for clients with NSLBP to decrease the chance of the pain returning. If the client is having an acute flare-up trainers should not perform any exercises and mandate a brief rest period for the client.

Individuals will experience pain in different ways so sitting on a bike may not be comfortable for some, and walking on a treadmill could cause pain for others. Fitness professionals must work closely with the client to find exercises that will promote stability and strength in the core.

Adherence to exercise may be difficult to achieve with individuals suffering with chronic NSLBP, but functionality can improve quickly, and long term benefits begin after only two months of training. Exercise should be generally tolerable and should only leave clients mildly sore.

Exercise Guidelines for Individuals with Nonspecific Low Back Pain

Frequency

- 3-5 days per week- progress to everyday

Intensity

- Moderate 40-60% maximum HR

Duration

- Build up to 20-60 minutes, 10-minute bouts throughout the day

Mode

- Brisk walk with arm movement, cycling (if possible), swimming

Special Considerations

- Low impact is best initially.

- Individuals are typically deconditioned so start low and slow, progress as tolerated.

- Avoid exercising on unstable surfaces (stability ball) early in training.

- Monitor symptoms and pain tolerance levels, adjust workout accordingly.

Summary

Special populations clients are frequently encountered in the personal training setting. Well-trained fitness professionals have the ability to modify and deliver fitness programs to a variety of clients. As such, knowledge of special populations training protocols is key for certified personal trainers.

References

- Bangsbo J, Krustrup P, Duda J, et al. The Copenhagen Consensus Conference 2016: Children, youth, and physical activity in schools and during leisure time. British Journal of Sports Medicine. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/50/19/1177.short. Published October 1, 2016.

- Hill JO. Dietary and Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Obesity Management. 2008;4(6):317-318. https://doi.org/10.1089/obe.2008.0240

- Myers J, Nieman DC, American College Of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Resources for Clinical Exercise Physiology: Musculoskeletal, Neuromuscular, Neoplastic, Immunologic, and Hematologic Conditions. Lww; 2011.

- CDC. How are Children Different from Adults? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published August 2, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/childrenindisasters/differences.html

- Armstrong N, Tomkinson G, Ekelund U. Aerobic fitness and its relationship to sport, exercise training and habitual physical activity during youth. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011;45(11):849-858. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2011-090200

- Ehrman JK, Gordon PM, Visich PS, Keteyian SJ. Clinical Exercise Physiology. Human Kinetics; 2013

- Degischer S, Labs KH, Hochstrasser J, Aschwanden M, Tschoepl M, Jaeger KA. Physical training for intermittent claudication: a comparison of structured rehabilitation versus home-based training. Vascular Medicine. 2002;7(2):109-115. https://doi.org/10.1191/1358863x02vm432oa

- Gregory Haff G. ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION: Youth Resistance Training. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2003;25(1):49.doi:2.0.co;2″>10.1519/1533-4295(2003)025<0049:rdyrt>2.0.co;2

- Blimkie CJR. Resistance Training During Preadolescence. Sports Medicine. 1993;15(6):389-407. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199315060-00004

- US Census Bureau. Search Results. The United States Census Bureau. Published April 4, 2019

- Janaudis-Ferreira T. Exercise training improves exercise capacity and quality of life in people with interstitial lung disease [synopsis]. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2017;63(4):257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2017.07.002

- Older Americans Key Indicators of Well-Being. Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics; 2008

- Goble DJ, Coxon JP, Wenderoth N, Van Impe A, Swinnen SP. Proprioceptive sensibility in the elderly: Degeneration, functional consequences and plastic-adaptive processes. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;33(3):271-278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.012

- CDC. Targeting Arthritis: Recuding disability for 43 million Americans: at glance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published 2006

- Gallagher D, Ruts E, Visser M, et al. Weight stability masks sarcopenia in elderly men and women. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;279(2):E366-E375

- Aronow W. Peripheral arterial disease in the elderly. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2008;Volume 2(93):645-654. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.s2412

- Gagliardi C. Considerations for Training the Pre- and Postnatal Client. www.acefitness.org. Published 2018. https://www.acefitness.org/fitness-certifications/ace-answers/exam-preparation-blog/3664/considerations-for-training-the-pre-and-postnatal-client

- Ogden C. State-Specific Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults—United States, 2005. JAMA. 2006;296(16):1959. doi:10.1001/jama.296.16.1959

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. Published June 9, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- Meeuwsen S, Horgan GW, Elia M. The relationship between BMI and percent body fat, measured by bioelectrical impedance, in a large adult sample is curvilinear and influenced by age and sex. Clinical Nutrition. 2010;29(5):560-566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2009.12.011

- Haslam D, Sattar N, Lean M. Obesity—time to wake up. BMJ. 2006;333(7569):640-642. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.333.7569.640

- OGITA F, STAM RP, TAZAWA HO, TOUSSAINT HM, HOLLANDER AP. Oxygen uptake in one-legged and two-legged exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2000;32(10):1737-1742. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200010000-00012

- VA C, LG O, J S, et al. PHYSICAL ACTIVITY PATTERNS IN THE NATIONAL WEIGHT CONTROL REGISTRY. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2008;28(5):346. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.hcr.0000336176.41074.d3

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017 Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States Background.; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf

- Kim KS, Park SW. Exercise and Type 2 Diabetes: ACSM and ADA Joint Position Statement. Journal of Korean Diabetes. 2012;13(2):61. https://doi.org/10.4093/jkd.2012.13.2.61

- Diabetes Report Card. Center for Disease Control (CDC). Published 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard.html

- American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2022 update:a report from the American Heart Association[published online ahead of print Wednesday, January26,2022]. Circulation. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052

- Trout HH. Kinetics of cellular proliferation after arterial injury II. Inhibition of smooth muscle growth by heparin. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 1986;4(5):540-541. https://doi.org/10.1016/0741-5214(86)90401-5

- Coronary Artery Disease Progression in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes and Diabetes Mellitus. Case Medical Research. Published online March 26, 2019. https://doi.org/10.31525/ct1-nct03890822

- Tian D, Meng J. Exercise for Prevention and Relief of Cardiovascular Disease: Prognoses, Mechanisms, and Approaches. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2019;2019:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3756750

- Christodoulou C. What is osteoporosis? Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2003;79(929):133-138. https://doi.org/10.1136/pmj.79.929.133

- Cawthon PM. Gender Differences in Osteoporosis and Fractures. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2011;469(7):1900-1905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-011-1780-7

- Robling AG, Turner CH. Mechanical Signaling for Bone Modeling and Remodeling. Critical ReviewsTM in Eukaryotic Gene Expression. 2009;19(4):319-338. https://doi.org/10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v19.i4.50

- ROBLING AG. Is Bone’s Response to Mechanical Signals Dominated by Muscle Forces? Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2009;41(11):2044-2049. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e3181a8c702

- Shayan Senthelal, Thomas MA. Arthritis. Nih.gov. Published November 14, 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK518992/

- Bullock, Jacqueline, et al. “Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Brief Overview of the Treatment.” Medical Principles and Practice, vol. 27, no. 6, 2 Sept. 2018, pp. 501–507, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6422329/, 10.1159/000493390

- National Cancer Institute. “NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms.” National Cancer Institute, Cancer.gov, 2019, www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/cancer

- American Cancer Society. “Cancer Facts & Figures 2022| American Cancer Society.” www.cancer.org, 2022, www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2022.html.

- Woods, JA, et al. “Exercise and Cellular Innate Immune Function.” Rehabilitation Oncology, vol. 19, no. 2, 2001, p. 34, 10.1097/01893697-200119020-00043. Accessed 22 Mar. 2020

- Bhatta, Dharma N., and Stanton A. Glantz. “Association of E-Cigarette Use with Respiratory Disease among Adults: A Longitudinal Analysis.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, vol. 58, no. 2, Dec. 2019, 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.028

- Martinez-Pitre, Pedro J., et al. “Restrictive Lung Disease.” PubMed, StatPearls Publishing, 2020, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560880

- Celli, Bartolome R., et al. “Dyssynchronous Breathing during Arm but Not Leg Exercise in Patients with Chronic Airflow Obstruction.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 314, no. 23, 5 June 1986, pp. 1485–1490, 10.1056/nejm198606053142305. Accessed 6 June 2020.

- Treat-Jacobson, Diane, et al. “Optimal Exercise Programs for Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association.” Circulation, vol. 139, no. 4, 22 Jan. 2019, 10.1161/cir.0000000000000623.

- Hackam, Daniel G. “Medical Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease.” JAMA, vol. 296, no. 1, 5 July 2006, p. 41, 10.1001/jama.296.1.41-a. Accessed 6 Jan. 2020.

- Cassidy, J David, et al. “Incidence and Course of Low Back Pain Episodes in the General Population.” Spine, vol. 30, no. 24, Dec. 2005, pp. 2817–2823, 10.1097/01.brs.0000190448.69091.53. Accessed 11 Mar. 2021.

- Hodges, Paul W., and Carolyn A. Richardson. “Inefficient Muscular Stabilization of the Lumbar Spine Associated with Low Back Pain.” Spine, vol. 21, no. 22, Nov. 1996, pp. 2640–2650, 10.1097/00007632-199611150-00014. Accessed 7 Apr. 2020

- McGill, Stuart M. “Low Back Stability: From Formal Description to Issues for Performance and Rehabilitation.” Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, vol. 29, no. 1, Jan. 2001, pp. 26–31, 10.1097/00003677-200101000-00006.